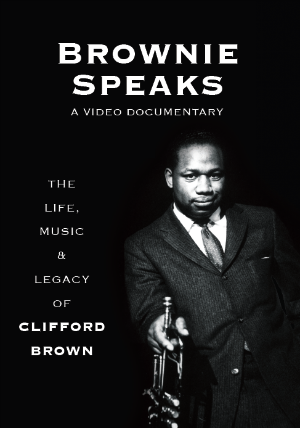

When Clifford Brown perished in an automobile accident in June 1956, the jazz world mourned the loss of the 25-year-old trumpeter for both his remarkable accomplishments and for his potential future. In the final two years of his life, Brown worked with Max Roach, co-leading one of the finest small groups in jazz history. The group created many outstanding recordings with Harold Land as tenor saxophonist, but when Sonny Rollins replaced Land in late 1955, it became, in Dan Morgenstern’s words, “a force of nature”. After Brown’s death, Rollins said, We were just starting to achieve a sound when the accident happened. On the last job we played together, all of a sudden we both heard it. We were phrasing, attacking, breathing together. It is entirely conceivable that Brown, Rollins and Roach might have led jazz into new directions in the latter part of the 1950s. Further, such a development might have delayed, adapted or stifled the free jazz movement led by Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor. Of course, these theories are not nearly as important as the actual legacy that Clifford Brown left behind. In the long-awaited documentary “Brownie Speaks”, director Don Glanden lets Brown’s friends, family and fellow musicians tell the trumpeter’s story without the assistance of a voice-over narrator.

When Clifford Brown perished in an automobile accident in June 1956, the jazz world mourned the loss of the 25-year-old trumpeter for both his remarkable accomplishments and for his potential future. In the final two years of his life, Brown worked with Max Roach, co-leading one of the finest small groups in jazz history. The group created many outstanding recordings with Harold Land as tenor saxophonist, but when Sonny Rollins replaced Land in late 1955, it became, in Dan Morgenstern’s words, “a force of nature”. After Brown’s death, Rollins said, We were just starting to achieve a sound when the accident happened. On the last job we played together, all of a sudden we both heard it. We were phrasing, attacking, breathing together. It is entirely conceivable that Brown, Rollins and Roach might have led jazz into new directions in the latter part of the 1950s. Further, such a development might have delayed, adapted or stifled the free jazz movement led by Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor. Of course, these theories are not nearly as important as the actual legacy that Clifford Brown left behind. In the long-awaited documentary “Brownie Speaks”, director Don Glanden lets Brown’s friends, family and fellow musicians tell the trumpeter’s story without the assistance of a voice-over narrator.

The film is a treasure trove for die-hard Brownie fans. The soundtrack includes excerpts from nearly 50 rare and classic Brown recordings, along with several images of rare 10-inch LP covers. Brown’s single film appearance—a 1956 guest shot on Soupy Sales’ Detroit TV show—is also here, but due to the high price of the footage, Glanden only includes a few seconds of the clip to acknowledge its existence. Since this is the first documentary ever made about Clifford Brown, many of the interviewees have never been seen on camera before. And what stories they tell! Many fans knew that “Ida Red”, a song Brown recorded at his first session with Chris Powell and the Blue Flames, referred to his girlfriend Ida Mae, but Glanden not only presents an interview with her, but displays rarely seen photos of Brown with the Powell band! Brown was involved in several serious car accidents during his short life (the 1950 accident has been well-documented, but the one that occurred during his childhood has never been mentioned in any other Brown biographies or articles, nor have the two incidents from the Chris Powell era recalled here by saxophonist Vance Wilson). And Brown’s widow, LaRue, reveals that the trumpeter agreed to record “Clifford Brown with Strings” only when LaRue agreed to start a family (In 1983, I was LaRue’s houseguest for three weeks. We talked a lot about Brownie, but she never told me that story!)

As Harold Land states in the film, words can’t do Clifford Brown justice, and there’s no substitute for listening to his music. As a long-time fan who owns copies of all of Brown’s extant recordings, I completely agree, but I wondered if the film would entice a newcomer to explore Brown’s music. I played the film for a friend who had musical background but limited exposure to Brown, and asked for her honest reactions. She was fascinated with Brownie’s sound and the joy he communicated through his horn. She was amazed at the speed and precision of his improvisations, but was frustrated with the short length of the film’s musical excerpts (She was particularly annoyed that after hearing someone talk about Brown’s ability to play extremely long phrases, none of the examples displayed Brown demonstrating that skill). Although the documentary is only 87 minutes long, it is quite leisurely paced, and there’s about a half-hour of biographical information before we reach Brownie’s first commercial recordings. There is also a jarring continuity problem: After Land talks about the origins of the Brown/Roach quintet, he states that the group was based in Philadelphia and toured on the East Coast. That’s true, but the group started in California and recorded several albums in LA before moving East; two of those West Coast recordings are discussed later in the film: the all-star “Best Coast Jazz” and the posthumously titled Pacific Jazz album “Jazz Immortal” (featuring the Brown original, “Tiny Kapers”).

It took 20 years between the conception of “Brownie Speaks” and its completion. Several of the interviewees have passed away in the intervening years (including Dizzy Gillespie, Harold Land, LaRue Brown-Watson, and Donald Byrd) while technology moved brazenly forward. The video and audio quality of the interviews varies considerably throughout the film, but Glanden’s son Brad has edited the material skillfully, making the overall film as consistent as possible. The film is presented in widescreen format, but my copy of the DVD was not enhanced for 16×9 televisions (a problem which could be corrected on a subsequent pressing). Overall, “Brownie Speaks” is a remarkable achievement. As my friend will verify, it can generate new Clifford Brown fans, while it can educate and enlighten those who have loved Brown’s music for many years. It was worth the wait.