“Shuffle Along” was not the first black Broadway musical, but its 1921 premiere broke a twelve-year drought of black shows on the so-called Great White Way. After a harrowing production history, it became one of the most successful productions of its time, with nearly 500 performances logged during its initial Broadway run. The script was authored by Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, two old-time black vaudevillians who also starred in the show, performing in blackface. The music was created by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake (pictured, L to R), who contrasted the outdated comedy with a scored peppered with jazz. The cast included artists who would become major figures in black music, including Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, Florence Mills, Adelaide Hall, and Fredi Washington. The orchestra included composers Hall Johnson and William Grant Still. The show attracted established white theatergoers as well as blacks, who were allowed to sit in the orchestra section of the audience for the first time in Broadway history. For many white theater patrons, “Shuffle Along” may have been their first exposure to jazz played by black performers.

“Shuffle Along” was not the first black Broadway musical, but its 1921 premiere broke a twelve-year drought of black shows on the so-called Great White Way. After a harrowing production history, it became one of the most successful productions of its time, with nearly 500 performances logged during its initial Broadway run. The script was authored by Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, two old-time black vaudevillians who also starred in the show, performing in blackface. The music was created by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake (pictured, L to R), who contrasted the outdated comedy with a scored peppered with jazz. The cast included artists who would become major figures in black music, including Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, Florence Mills, Adelaide Hall, and Fredi Washington. The orchestra included composers Hall Johnson and William Grant Still. The show attracted established white theatergoers as well as blacks, who were allowed to sit in the orchestra section of the audience for the first time in Broadway history. For many white theater patrons, “Shuffle Along” may have been their first exposure to jazz played by black performers.

Before getting too excited about that last statement, it’s important to remember the state of jazz in 1921. It was a music still developing its basic language. When “Shuffle Along” opened in May 1921, many of the musicians now considered as jazz pioneers had not yet made their first recordings. Louis Armstrong was still living in New Orleans (and by his own admission, would have stayed there indefinitely had King Oliver not hired him to come to Chicago). The first recordings of Armstrong, Oliver, Sidney Bechet, Jelly Roll Morton and Freddie Keppard all came out in 1923. What preceded them were sides by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Johnny Dunn, James Reese Europe, James P. Johnson, Kid Ory, Paul Whiteman and a handful of female blues singers (not all of whom sang authentic blues). With the exception of the ODJB and Whiteman sides, most of the early recordings were made for the “race market”. It’s safe to say that many white listeners of the time were probably unaware that jazz was originally created by blacks, so unlike the following generations of white jazz fans, they did not venture into black neighborhoods to hear the music or purchase the recordings. Eubie Blake understood this better than anyone, and he deliberately toned down the jazz content in “Shuffle Along” so that white audiences could better comprehend it.

The comedy team of Miller and Lyles first met the musical team of Sissle and Blake at a NAACP benefit in 1920. Later, they reunited in New York, where the comedians told the musicians that they wanted to collaborate on a Broadway show. Once a producer was found, the show was plagued by money problems throughout its rehearsal and preview period. The theater needed major renovations, the costumes were taken from a previous show (there were sweat marks present under the sleeves), and the cast was stranded on several occasions because there was not enough money for train fare to get to the next tour stop. One day during the preview tour, Sissle sat on the steps of a building writing checks that could not be cashed until the box office receipts reached the bank in New York. Blake noticed that while doing this nefarious business, Sissle happened to be sitting on the steps of the local jail!

The script was based on Miller and Lyles’ old vaudeville sketch “The Mayor of Jimtown” (aka “The Mayor of Dixie”) and it was filled with horrid stereotypes: Miller and Lyles played the co-owners of a grocery store, both of whom decide to run for mayor. They each steal from the cash register to buy votes, unwittingly hire the same New York private detective to catch the other partner stealing, and show an utter lack of education (when one of the partners becomes mayor, he can’t pass a law against black cats because he can’t spell “cat”). While the bits were played for laughs, many black leaders decried the abominable characterizations. However, the music was highly praised in all corners, even the potentially-controversial “Love Will Find a Way”, which was the first staged example of a romantic duet between two black characters. Black critic Lester A. Walton noted the song’s excellence, writing that “If ‘Love Will Find a Way’ were featured in a white production, it would be proclaimed as one of the season’s hits.”

A new production of “Shuffle Along” is set to open on Broadway on April 28, 2016, and with it has come a pair of new CDs with songs from the show. Before discussing those recordings, we turn to an earlier album which  collected recordings by the show’s composers, actors and their immediate contemporaries. In celebration of the US Bicentennial in 1976, New World Records—with support from the federal government—created a series of 100 LPs documenting American music. These superbly packaged and annotated albums were distributed for free to libraries all across the country. There were several fine collections of jazz sides, plus contemporary classical music, classic country and roots recordings, and historical Broadway shows. Their re-creation of “Shuffle Along” (NW 260) consists of acoustic recordings made between 1919 and 1924. The producers did not have access to the original libretto, but Sissle and Blake listened to the remastered recordings to ensure that they were reproduced at the proper speed and pitch. Sissle passed away as the album neared release, and the album was dedicated to his memory. Blake lived until 1983, claiming to be over 100 years old—although documents discovered in recent years prove that he was 97 when he died.

collected recordings by the show’s composers, actors and their immediate contemporaries. In celebration of the US Bicentennial in 1976, New World Records—with support from the federal government—created a series of 100 LPs documenting American music. These superbly packaged and annotated albums were distributed for free to libraries all across the country. There were several fine collections of jazz sides, plus contemporary classical music, classic country and roots recordings, and historical Broadway shows. Their re-creation of “Shuffle Along” (NW 260) consists of acoustic recordings made between 1919 and 1924. The producers did not have access to the original libretto, but Sissle and Blake listened to the remastered recordings to ensure that they were reproduced at the proper speed and pitch. Sissle passed away as the album neared release, and the album was dedicated to his memory. Blake lived until 1983, claiming to be over 100 years old—although documents discovered in recent years prove that he was 97 when he died.

The New World album opens with Blake conducting the show’s orchestra in a medley of two of the production’s biggest hits, “Bandana Days” and“I’m Just Wild about Harry”. The orchestra does not swing, but it plays with great vitality, and on “Harry”, Blake plays a vibrant bit of ragtime-cum-stride piano. Next, Sissle performs “In Honeysuckle Time” with a small combo dominated by a too-closely-recorded banjo and a trumpeter with a herky-jerky sense of rhythm. Sissle and Blake’s duet version of “Love Will Find a Way” follows, and Blake’s piano accompaniment moves from a traditional background in the first chorus to a much more rhythmic feeling in the second. Their duet on “Bandana Days” makes great use of the song’s syncopated rhythms, and Blake steals the spotlight with a fine stride solo behind Sissle’s spoken commentary. Tim Brymm’s Black Devil Orchestra backs Gertrude Saunders’ version of “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home?” Saunders was the show’s first ingénue lead, and she had a big classically-trained voice which she tried to adapt to blues style. She was replaced by Florence Mills, who had a much smaller, intimate voice, It is all the more unfortunate that Mills did not make any recordings before her premature death, for critics of the time praised her less intense stage renditions of the songs. Blake’s dynamite solo medley of “Baltimore Buzz” and “In Honeysuckle Time” follows, and its powerful rhythmic drive and crisp articulations puts it in the same exalted category as James P. Johnson’s “Keep off the Grass” and “Carolina Shout” recorded later that year. Interestingly enough, Paul Whiteman’s cover version of “Gypsy Blues” offers the most modern rhythmic approach on the album: they achieve a fine swaying feel throughout, which holds steady even in the awkward double-time episode near the end of the side.

Saunders and Brymm return for “I’m Craving for That Kind of Love”, the refrain of which includes a repeated request to “kiss me”. Saunders overplays the entire song, and again it was Florence Mills who received the most acclaim for this song. The labored comedy of Miller and Lyles follows on a side called “The Fight” (renamed “Jimtown Fisticuffs” on the Harbinger disc below). This skit appeared in the second act, and may have been another holdover from their vaudeville act. The remainder of the album features Sissle with his own orchestra and the James Reese Europe’s 369th Infantry Hell Fighter Band. Most of the songs are from Sissle and Blake’s duet repertoire, and were among the pieces performed by the duo in a specialty set inserted late in the second act of “Shuffle Along”. “Gee, I’m Glad That I’m From Dixie” usually opened the set, and the World War I-inspired “On Patrol In No Man’s Land” was the typical closer. The brief version of “How Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm” may be the best of these sides, with Europe’s light-footed military band keeping rhythmic pace with Sissle’s lithe vocals. Sissle’s version of the show’s finale, “Baltimore Buzz”—apparently with the same banjo and trumpet as on “In Honeysuckle Time”—is an acceptable, but underwhelming close to the album. The New World album’s primary virtue comes from its dedication to recordings of the period and for its superb liner notes. Due to licensing regulations, the original album is no longer available from New World. However, the notes can be found online here, and if interested listeners cannot find a copy of the vinyl at a library (or purchase a copy online), there is an unauthorized MP3 dub of the album available from Amazon here.

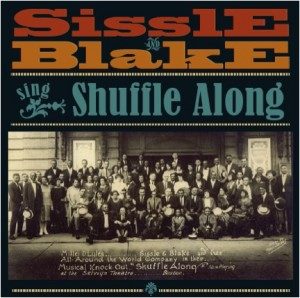

Harbinger’s new CD of historical recordings, “Sissle and Blake Sing ‘Shuffle Along’” (HCD 3204) contains a superb liner essay by Richard Carlin and  producer Ken Bloom detailing the production and reception of the show. However, they seem to have forgotten that a CD was included in the package: there is no track-by-track analysis of the recordings, no personnel and no discographical information. A brief note on the inside front cover tells us that some of the sides come from Blake’s EBM label, others from a demo prepared for a proposed 1950 revival of the show, and the rest are a hodgepodge of archival recordings. Three tracks are duplicated from the New World LP: Blake’s “Baltimore Buzz”, Saunders’ “Daddy” and the aforementioned Miller and Lyles “The Fight”/“Jimtown Fisticuffs”. Using the recently discovered and published libretto, Harbinger places the music in the original show order, with songs added during the show’s run placed in an appendix at the end of the disc.

producer Ken Bloom detailing the production and reception of the show. However, they seem to have forgotten that a CD was included in the package: there is no track-by-track analysis of the recordings, no personnel and no discographical information. A brief note on the inside front cover tells us that some of the sides come from Blake’s EBM label, others from a demo prepared for a proposed 1950 revival of the show, and the rest are a hodgepodge of archival recordings. Three tracks are duplicated from the New World LP: Blake’s “Baltimore Buzz”, Saunders’ “Daddy” and the aforementioned Miller and Lyles “The Fight”/“Jimtown Fisticuffs”. Using the recently discovered and published libretto, Harbinger places the music in the original show order, with songs added during the show’s run placed in an appendix at the end of the disc.

The CD opens with a duet between Blake and vocalist Ivan Harold Browning. Their medley features many of the show’s hits including “If You’ve Never Been Vamped by a Brownskin”, “In Honeysuckle Time” and “I’m Just Wild About Harry”. Browning was part of the Harmony Kings, a male quartet incorporated into the show in the summer of 1921 (this was the group that offered Paul Robeson his first experience on the stage), and in this 1971 recording, Browning’s voice still sounds very good, despite his advanced age. Blake pipes in with vocal support at the end of each song, and he offers a vivacious solo on “Harry”. “Election Day” is the first of eight excerpts from the 1950 demo tape, and Sissle sings all of the parts and gives spoken descriptions of the stage action. Blake’s full piano accompaniment evokes an entire pit orchestra, and the earnestness of the presentation makes the listener wonder why it took two years for the revival to be staged. We go back to the early 1920s for Miller & Lyles’ skit “Election Day in Jimtown”. The comedy is offensive and dated, but Doug Pomeroy’s superb remastering captures as much fidelity as the ancient recording ever held. “I’m Simply Full of Jazz” is another acoustic recording with Sissle on vocals. The lively background is uncredited, both here and in Tom Lord’s onlne “Jazz Discography”. Browning sings a sentimental rendition of “Love Will Find a Way” in another duet from the 1970s, followed by three further excerpts from the 1950 demo, “Bandana Days”, “Mirandy”/“In Honeysuckle Time” and “Gypsy Blues”. “Bandana” has a few interesting updates, including an energetic soft shoe by Sissle as well as references to beboppers and jitterbugs.

An uncredited (and very jangly) QRS piano roll medley serves as an entr’acte. The show’s title song is represented by the 1950 demo with a remarkable accompaniment by Blake and a few more dynamic vocal and soft shoe moments from Sissle. “I’m Just Wild About Harry” sounds like it’s from the demo tape as well, but there is no documentation to support my supposition. Ruth Williams joins Sissle for a fine duet on this standard. The Miller and Lyles “Fight” comes next, sounding much clearer than the New World transfer. The next five tracks all feature Sissle, but they jump back and forth between the 1950 demo and 1920 archive recordings. The audio transitions are jarring to say the least. Harbinger promises that they will release the complete 1950 demo in the future, and I wish that they had just released it now as a separate entity rather than mixing in with all of the other historical recordings. I can appreciate the concept of placing the music in show order, but as an audio experience, it just doesn’t work. The CD concludes with Blake’s solo “Baltimore Buzz”, Sissle’s “Pickaninny Shoes” (from an electric recording made in the mid- to late 1920s), the Saunders/Brymm “Daddy” and one last Miller and Lyles routine “Fourth of July in Jimtown”.

Despite his youthful age (37 this year) and appearance, pianist Ehud Asherie is one of the most historically astute musicians on the jazz scene  today. His latest album contains nine fresh solo versions of songs from “Shuffle Along” (Blue Heron—no catalog number). His arrangement of “Gypsy Blues” uses a single note bass line against finely detailed middle register chords and delicately played treble lines. His first version of “I’m Just Wild About Harry” opens in a rubato tempo to allow a deeper exploration of the inner harmony, then moves into a jubilant rendition of the verse over a pedal point bass before finally going into a dazzling up-tempo jaunt through the melody. On this section, he creates a unique mix of the styles of Art Tatumand Bud Powell without sounding like a carbon copy of either. The coda wraps up the arrangement with short recollections of each episode. Later on the disc, he revisits “Harry” in its original waltz tempo (Blake originally changed the style to a one-step on the suggestions of Sissle and leading lady Lonnie Gee). Over the course of the 40-minute recital, he examines songs like “Everything Reminds Me of You” and “Goodnight Angeline” which were added to the show during its run, as well as the better-known hits like “I’m Craving for That Kind of Love”, “Bandana Days”, “If You’ve Never Been Vamped by a Brownskin” and “Love Will Find a Way”. In Asherie’s hands, these songs belie their age of 95 years (and older!); perhaps that’s because these songs haven’t played to death like other standards, but it’s more likely that Asherie’s sensitive performances give these songs a new life, anchored within the vivid imagination of a gifted player.

today. His latest album contains nine fresh solo versions of songs from “Shuffle Along” (Blue Heron—no catalog number). His arrangement of “Gypsy Blues” uses a single note bass line against finely detailed middle register chords and delicately played treble lines. His first version of “I’m Just Wild About Harry” opens in a rubato tempo to allow a deeper exploration of the inner harmony, then moves into a jubilant rendition of the verse over a pedal point bass before finally going into a dazzling up-tempo jaunt through the melody. On this section, he creates a unique mix of the styles of Art Tatumand Bud Powell without sounding like a carbon copy of either. The coda wraps up the arrangement with short recollections of each episode. Later on the disc, he revisits “Harry” in its original waltz tempo (Blake originally changed the style to a one-step on the suggestions of Sissle and leading lady Lonnie Gee). Over the course of the 40-minute recital, he examines songs like “Everything Reminds Me of You” and “Goodnight Angeline” which were added to the show during its run, as well as the better-known hits like “I’m Craving for That Kind of Love”, “Bandana Days”, “If You’ve Never Been Vamped by a Brownskin” and “Love Will Find a Way”. In Asherie’s hands, these songs belie their age of 95 years (and older!); perhaps that’s because these songs haven’t played to death like other standards, but it’s more likely that Asherie’s sensitive performances give these songs a new life, anchored within the vivid imagination of a gifted player.

Sissle and Blake tried to revive “Shuffle Along” in 1932 and 1952, both to disastrous results: the 1932 show closed after 17 performances and the 1952 version only lasted for four performances (Ironically, RCA Victor recorded four excerpts from the 1952 show, only to find that the show was closed by the time the record was released). At press time, an original cast of the new Broadway revival was not available—even as a pre-order—so we don’t know what songs from the original score will appear in the new version. We do know that writer-director George C. Wolfe’s new script includes stories from the production of the original show (which is actually a better story than the original script). Using the historical angle will also present any portions of the original show in a better context, as it will show the racial stereotypes as things of the past. The new show’s cast is quite impressive with Audra McDonald, Brian Stokes Miller, Billy Porter, Brandon Victor Dixon and Joshua Henry all playing principal roles, and Savion Glover providing the choreography. The success of this version of “Shuffle Along” will depend on the strength of the revised work and the reaction of its audiences, but with such a fine cast and crew, it should do justice to this hallowed piece of black theater history.