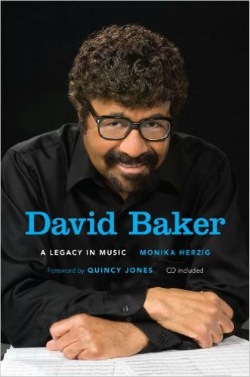

David Baker, who passed away March 26, 2016 at the age of 84, was one of jazz’s true Renaissance men. Best known as a pioneer of jazz education, Baker was also a musician, author, composer, conductor, historian and activist. In her 2011 collection of essays, “David Baker: A Legacy in Music” (Indiana University Press), Monika Herzig celebrates Baker’s many talents. Of the book’s nine extended chapters, Herzig wrote two essays herself, and collaborated on two others. For the rest, she called upon three fellow members of the Indiana University Jacobs Music School faculty, plus two other renowned jazz educators and a pair of well-known jazz writers. The result is a book that openly celebrates its subject, but is not always effective in relaying its wealth of information.

David Baker, who passed away March 26, 2016 at the age of 84, was one of jazz’s true Renaissance men. Best known as a pioneer of jazz education, Baker was also a musician, author, composer, conductor, historian and activist. In her 2011 collection of essays, “David Baker: A Legacy in Music” (Indiana University Press), Monika Herzig celebrates Baker’s many talents. Of the book’s nine extended chapters, Herzig wrote two essays herself, and collaborated on two others. For the rest, she called upon three fellow members of the Indiana University Jacobs Music School faculty, plus two other renowned jazz educators and a pair of well-known jazz writers. The result is a book that openly celebrates its subject, but is not always effective in relaying its wealth of information.

The book starts out as a biography. IU associate professor Lissa May opens the book with a brief summary of Baker’s childhood and formative years. Aside from a few minor errors (John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley were not yet major players in the late 1940s, when Baker was a teen) May’s chapter offers a solid beginning to Baker’s story. Herzig picks up the narrative through the next chapter, which tells of Baker’s college education (with both a bachelors and masters from IU) and his experiences as a working trombonist both as a free-lancer in Indianapolis and as a member of the George Russell Sextet. She then backtracks in the next chapter to discuss the 1953 automobile accident which eventually caused Baker to give up the trombone a decade later. It was during the mid-60s—with Baker out of work, and changing his primary instrument to cello—that the opportunity arose for him to develop a full-fledged jazz studies program at Indiana.

In retrospect, it is quite amazing that Baker landed the Indiana job at all. By 1966, Baker’s teaching experience added up to less than a year at a university in Missouri, a brief residence with Russell at the Lenox School of Jazz, and several years of private teaching. Jerry Coker, who was leaving IU to launch a full-time jazz program at the University of Miami, recommended Baker without reservation—or offering a second choice. Baker’s race and his short teaching résumé caused Indiana’s Dean Wilfred Bain to hesitate about hiring Baker. But Baker already had detailed plans about how to run and maintain a jazz studies program, and two years after Baker was hired, the school offered its first bachelor’s degree in jazz studies. Once Herzig tells of Baker’s new job at Indiana, the biography suddenly ends. Anyone wanting to follow the story of Baker’s family life or his later accomplishments must try to piece together the tale from occasional references within the remainder of the text. Regrettably, some stories are not told at all: Baker’s second wife, Lida, played flute in Baker’s 21stCentury Bebop Band, and was an staunch supporter of her husband’s work; yet we never learn anything about her background, how she met David, or the transition between David’s two marriages.

From this point forward, the book takes on the various aspects of Baker’s career separately. Following Nathan Davis’ glowing endorsement of Baker’s talents as an educator, JB Dyas offers a detailed discussion of Baker’s ear-training and improvisation courses. Dyas’ essay is probably the most valuable portion of the volume. Anyone who has struggled through a basic ear-training course will be amazed at the depth of Baker’s approach (Dyas admits that few students ever made it to the most advanced level). Baker’s method of assigning scales—diatonic, modal or invented—to specific chords was a logical outgrowth of Russell’s Lydian method, but it was only the means to the end: Baker always encouraged his students to discover a personal approach to improvising. The next chapter starts with Herzig’s appreciation of Baker’s acclaimed combo, the 21st Century Bebop Band, followed by Brent Wallarab’s essay on Baker’s big band compositions. While some of his comments are valuable, Wallarab gets carried away with his musical analysis. Near the end of his discussion of Baker’s “Dance of the Jitterbugs”, he goes completely off the rails with this comment: As in an epic Ellington blues, one can perceive social commentary. In this case, the struggle against conventional form, the acquisition of freedom, the development of new structures out of the chaos, and a return to the status quo—all are possible considerations. Further metaphors, political or social can be drawn from this, and it is irrelevant whether Baker was conscious of anything but the music itself. Oh, please. “Dance of the Jitterbugs” is a very good piece of music—the book’s enclosed CD includes an excellent recording by a big band co-led by Wallarab and Mark Buselli—but let’s not turn it into the “Communist Manifesto”.

One of the book’s appendices is a 30-page list of Baker’s original compositions including works for jazz and classical ensembles ranging in size from solos to symphony orchestras. In addition, IU adjunct professor David Ward-Steinman provides a sleep-inducing analysis of several of Baker’s works. It is here where the aforementioned CD could have played a pivotal role. Herzig compiled the disc’s tracks, but it doesn’t appear that Ward-Steinman agreed with her selections. One of the pieces doesn’t even rate a mention in Ward-Steinman’s text, and two others are written off within a few sentences. On Baker’s alto sax concerto, Ward-Steinman discusses only the first movement, while the CD offers the third movement! The CD includes a fine unreleased version of Baker’s “Roots II” featuring Sara Caswell on violin. Ward-Steinman acknowledges that Baker himself wrote a detailed description of the work in the notes for a recording by the Beaux Arts Trio, but apparently Ward-Steinman couldn’t be bothered to quote a passage or two (does he not realize that books generally stay in print longer than classical discs? In fact, the disc is presently out-of-print).

Before leaving the CD, it should be noted that it includes two brilliant jazz solos by Baker: a trombone solo on “Kentucky Oysters” with the Russell Sextet and a cello solo on “Groovin’ for Diz” with the 21st Century Bebop Band. On both of these solos, Baker stands apart from the rest of the band: “Oysters” has a triple-time feel throughout, but Baker resolutely plays his solo in duple time. He seems to play on an alternate set of chord changes on “Diz”; since the rhythm section continues with the same harmonies as before, it sounds like Baker is playing in a different key. However, knowing about Baker’s remarkable knowledge of jazz theory, I’m sure that could justify all of the notes he played!

The final section of the book deals with Baker’s work in public service and the government. Baker admitted reluctance to serve on federal arts boards, but understood that his stationary position as a music educator made him easier to contact than a touring musician. John Edward Hasse provides a vivid recollection of Baker’s tenure with the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, telling of the group’s origins (with Gunther Schuller and Baker serving as co-conductors for a time) and its eventual successes, including a tour of Egypt. Willard Jenkins discusses Baker’s work as a jazz advocate through the National Endowment for the Arts, and two ill-fated groups, the International Association of Jazz Educators and the National Jazz Service Organization. Herzig closes the book with a parade of testimonials by Baker’s friends and colleagues, followed by a full transcript of his keynote speech at the first convention of the Jazz Education Network.

The loss of David Baker is as huge a blow to jazz as the loss of Billy Taylor, Marian McPartland and Clark Terry. All of these musicians were vocal spokespersons for jazz, and all of them touched a large percentage of the jazz public both through their public appearances and private mentoring. One of the benefits of Baker’s pedagogical method is that it can be repeated and re-taught for many generations. For years, many believed that jazz was only an aural tradition and that it could never be taught. David Baker proved that theory wrong, and as proved by his long list of talented alumni (including Randy and Michael Brecker, Chris Botti, Sara and Rachel Caswell, and John Clayton) individualism need not be sacrificed in the process.