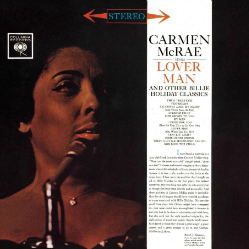

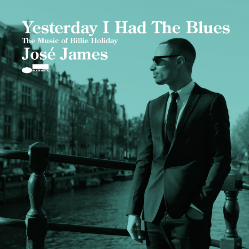

For many fans and historians, jazz vocalists come in two categories: Billie Holiday and everyone else. I have a similar feeling about Billie Holiday tribute albums—there’s Carmen McRae’s and everyone else’s. Now, since this essay is primarily a review of two new Holiday tribute albums by José James and Cassandra Wilson, I suspect that some of my readers will accuse me of making unfair comparisons. But stick with me, folks. Many of  the elements that made “Carmen McRae Sings ‘Lover Man’ and Other Billie Holiday Favorites” (Columbia 65115) such a triumph are present in James’ “Yesterday I Had the Blues” (Blue Note 228310) and Wilson’s “Coming Forth by Day”(Legacy 6362). On all three albums, the artists resist the urge to mimic Holiday’s sound and find their own ways to express themselves through Holiday’s repertoire. McRae certainly had advantages that the younger singers do not share: Holiday was not only a primary influence on McRae, but also a personal friend. McRae was introduced to Holiday and her music while she was still developing her own style, so that virtually everything McRae sang had Billie Holiday deeply embedded within. However, there is no doubt that James and Wilson have studied Holiday’s recordings and repertoire, and a great deal of thought went into producing each album.

the elements that made “Carmen McRae Sings ‘Lover Man’ and Other Billie Holiday Favorites” (Columbia 65115) such a triumph are present in James’ “Yesterday I Had the Blues” (Blue Note 228310) and Wilson’s “Coming Forth by Day”(Legacy 6362). On all three albums, the artists resist the urge to mimic Holiday’s sound and find their own ways to express themselves through Holiday’s repertoire. McRae certainly had advantages that the younger singers do not share: Holiday was not only a primary influence on McRae, but also a personal friend. McRae was introduced to Holiday and her music while she was still developing her own style, so that virtually everything McRae sang had Billie Holiday deeply embedded within. However, there is no doubt that James and Wilson have studied Holiday’s recordings and repertoire, and a great deal of thought went into producing each album.

Both McRae and James focused their albums on specific parts of Holiday’s career. McRae’s album features music that Holiday recorded between 1935 and 1944; James chose music from 1939’s “Strange Fruit” to the end of her career (Interestingly, each singer included one song from outside the time frame; McRae’s fine “If the Moon Turns Green” may have been left off the original LP for precisely this reason, but James’ “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” stayed in the lineup, and to my ears, that was a mistake. More on that below.) What makes James’ selection so astute is that Holiday made a deliberate change to her repertoire around the time she recorded “Strange Fruit” and began performing at Café Society. From this point, she featured lots of torch songs, and very few up-tempo tunes. Holiday’s ballad-heavy repertoire is perfectly matched to James’ vocal delivery throughout his album. Although James appears to have a fairly wide range, he deliberately narrows it down to match Holiday’s. For example, on “I Thought About You”, I have little doubt that James could have easily sung the high notes in the song’s climactic phrase, the one going back to you, but every time the phrase appears, James goes lower in his range to create a melodic paraphrase instead of reaching for the upper notes.

For all three vocalists, the lyrics are a primary focus. Time and again, James finds remarkable ways to emphasize the meaning of the words. On the opening track, “Good Morning Heartache”, he frequently drops the first word of the title, making the imaginary salutation even more informal. And he holds back the final phrase, Good morning heartache, sit down, until the very end of the arrangement, which increases its dramatic effect. “Lover Man” is a song of the night, and James’ version is slow and highly erotic. In a rendition that will certainly appeal to both straight and gay listeners, James omits the word “Man” from the title phrase. This adds new subtext to the phrase, I long to try something I never had, and since the space for the missing word “Man” is still there, James makes us doubly aware of what he’s omitting. Wilson makes dramatic changes to the lyrics on her opening track, “Don’t Explain”. When Holiday sang it, she was quite forgiving to her dallying husband, but Wilson sounds like a spouse ready for revenge. In Wilson’s version, it’s the far more accusatory I see lipstick instead of Holiday’s skip that lipstick, and right or wrong, it matters instead of Holiday’s right or wrong don’t matter. Wilson even throws in an evil little laugh during Rob Marshall’s tenor sax solo. Since the liner notes mentioned the lyrics as a focal point of the album, I was expecting more subtle changes to the words but they never came. As usual, Wilson shows deep understanding of the lyrics through her smoky, intense delivery, but the re-writes are primarily limited to the first track.

more informal. And he holds back the final phrase, Good morning heartache, sit down, until the very end of the arrangement, which increases its dramatic effect. “Lover Man” is a song of the night, and James’ version is slow and highly erotic. In a rendition that will certainly appeal to both straight and gay listeners, James omits the word “Man” from the title phrase. This adds new subtext to the phrase, I long to try something I never had, and since the space for the missing word “Man” is still there, James makes us doubly aware of what he’s omitting. Wilson makes dramatic changes to the lyrics on her opening track, “Don’t Explain”. When Holiday sang it, she was quite forgiving to her dallying husband, but Wilson sounds like a spouse ready for revenge. In Wilson’s version, it’s the far more accusatory I see lipstick instead of Holiday’s skip that lipstick, and right or wrong, it matters instead of Holiday’s right or wrong don’t matter. Wilson even throws in an evil little laugh during Rob Marshall’s tenor sax solo. Since the liner notes mentioned the lyrics as a focal point of the album, I was expecting more subtle changes to the words but they never came. As usual, Wilson shows deep understanding of the lyrics through her smoky, intense delivery, but the re-writes are primarily limited to the first track.

As noted above, James makes one misstep in his album, and that is on “What a Little Moonlight Can Do”. While Holiday recorded this song several times during her career, all of the versions echo back to her original 1935 recording. On that track, Holiday did a sexual role-reversal on the song: instead of the wide-eyed innocent girl, Holiday made the woman the experienced partner and turned the boy into the nervous virgin. James’ version opens with his rhythm section of Jason Moran (piano), John Patitucci (bass) and Eric Harland (drums) breaking up the song’s rhythmic pulse. But when James enters, he doesn’t know what to do with the song. He croons through the tune without much conviction, never seeming to grasp the song’s message or its humor. This is the only up-tempo track on the album, and while the change of pace was necessary, it would have been better for James to find another song that would have fit the album’s concept. Wilson’s version of “Moonlight” is also rather strange. She sings it from a female perspective, without the gender  swap, and with a sense of wonder. She’s not playing a virgin, but she’s clearly in awe of the moon’s mystical powers. It seems to be a stretch for this wretched little pop song. McRae sings the song like Holiday did—which is still the best solution, as this song would have been long forgotten if Holiday had not put her unique spin on it.

swap, and with a sense of wonder. She’s not playing a virgin, but she’s clearly in awe of the moon’s mystical powers. It seems to be a stretch for this wretched little pop song. McRae sings the song like Holiday did—which is still the best solution, as this song would have been long forgotten if Holiday had not put her unique spin on it.

Although I have no doubt about Cassandra Wilson’s integrity, I’m not totally convinced about the integrity of her Holiday tribute. To be sure, there are many fine moments in this album, including her beautiful slow reading of “The Way You Look Tonight” and “Crazy He Calls Me”. The sole original on the album, “Last Song (For Lester)” is about Holiday not being allowed to sing at Lester Young’s funeral. This injustice hurt Holiday deeply, and the lyrics to the song are in the form of what might have been Holiday’s final message to her dear friend and companion. The song could be covered long beyond Wilson’s recording, but this version suffers from the same problem as the rest of the album: chronic over-arranging with completely inappropriate booms and crashes from the drums and guitars. Holiday’s art was in the small, subtle details—an improvised turn of a musical phrase to bring out a phrase in the lyric, or singing way behind the beat only to catch up with the band at the end of the phrase. Even when Holiday recorded with large orchestras, nothing was allowed to interfere with her vocal interpretation. That said, what Wilson and her band does to “Strange Fruit” is nothing short of criminal: drummer Thomas Wydler (of the rock band, The Yeah Yeah Yeahs) beats his drums mercilessly at the end of every line, while guitarists Kevin Breit and Nick Zinner wail incessantly. The effect of Lewis Allen’s eerie poem is completely lost in this utter travesty. In contrast, James creates a stunning a cappella version of the piece, with his overdubbed background vocals evoking a low black moan. James truly understands the power of this poem, and demonstrates—as Holiday did in 1939 and McRae did in 1961—that it is best conveyed as an understated horror story.