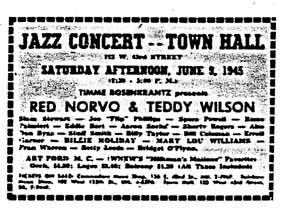

In June 1945, the world was a much different place than it is today. In April of that year, Franklin D. Rooseveltdied after serving twelve years as US President. In May, World War II ended in Europe with the unconditional surrender of Germany; within two weeks, many civilians first heard about the concentration camps and the Holocaust. War was still raging in the Pacific, only to be concluded with the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The nuclear age brought new tension and anxieties, and in jazz, the stress of the world was reflected in a new music called bebop. On June 9, 1945, when Timme Rosenkrantz (left) staged a swing concert at New York’s Town Hall, bop had not yet overtaken swing as the predominant jazz style, but the signs were around for all to see.

In June 1945, the world was a much different place than it is today. In April of that year, Franklin D. Rooseveltdied after serving twelve years as US President. In May, World War II ended in Europe with the unconditional surrender of Germany; within two weeks, many civilians first heard about the concentration camps and the Holocaust. War was still raging in the Pacific, only to be concluded with the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The nuclear age brought new tension and anxieties, and in jazz, the stress of the world was reflected in a new music called bebop. On June 9, 1945, when Timme Rosenkrantz (left) staged a swing concert at New York’s Town Hall, bop had not yet overtaken swing as the predominant jazz style, but the signs were around for all to see.

One of bop’s fiercest critics, guitarist Eddie Condon, hosted a weekly series of Dixieland concerts at Town Hall in the mid-forties, and around the same time an organization called the New Jazz Foundation decided to produce bop concerts on the same stage. The most visible member of the NJF was Symphony Sid Torin, a disc jockey who was playing the newest records by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie over the New York airwaves. Torin hosted a pair of NJF-sponsored Parker/Gillespie Town Hall concerts on May 16 and June 22, 1945. Rosenkrantz, working on his own behalf, booked Town Hall for June 9—right between the two bop concerts—and Torin went to work discrediting Rosenkrantz and his proposed concert. Rosenkrantz usually had problems financing his grandiose ideas, so Torin had NJF members picket Town Hall, claiming that Rosenkrantz would not pay the musicians and that his headliners would not appear. Sure enough, when the agents of Billie Holiday, Erroll Garner and Mary Lou Williams heard about the pickets, they  refused to let them perform. Faced with a looming disaster, Rosenkrantz enlisted the aid of drummer Gene Krupa, who agreed to play the concert with his trio for free.

refused to let them perform. Faced with a looming disaster, Rosenkrantz enlisted the aid of drummer Gene Krupa, who agreed to play the concert with his trio for free.

The NJF’s tactics diminished ticket sales, but the concert took place as scheduled. Vibraphonist Red Norvobrought a new nine-piece band with trumpeter Shorty Rogers, trombonist Eddie Bert, clarinetist Aaron Sachs, tenor saxophonist Flip Phillips, pianist Teddy Wilson, guitarist Remo Palmieri, bassist Slam Stewart and drummer Specs Powell. This group was the house band for the concert. They played a long set on their own, and later, Wilson and Phillips fronted the rhythm section for a shorter, intimate set. Stewart also played a pair of exciting duets with tenor saxophonist Don Byas, and combos led by Krupa, trumpeter Bill Coleman and violinist Stuff Smith filled out the concert. Rosenkrantz recorded the entire concert with a pair of disc-cutting machines using 16” transcription discs. Later, those recordings were issued by several labels, including Moe Asch’s Disc (which also issued the first Jazz at the Philharmonic recordings) and Milt Gabler’s Commodore (which was the first label to pay Rosenkrantz’ musicians).

Rosenkrantz’ transcription discs are housed at the University Library of South Denmark. One might expect that the tracks of each ensemble would all appear together in a logical sequence; instead, each group’s tracks are scattered across the set. This seems to indicate that these discs are dubbed copies with the tracks re-sequenced to fit each side. We can only guess about the actual concert sequence based on Sachs’ recollections (he was the last surviving musician, and I interviewed him a few months before he died), the somewhat unreliable memoirs of Rosenkrantz, Dan Morgenstern’s notes for Mosaic’s Commodore box set, and the conflicting reports of Leonard Feather (his grumpy 1945 concert review for Metronome magazine and his more charitable 1973 liner notes for the Atlantic reissue of the concert). When Martin Williams included the Byas/Stewart version of “I Got Rhythm” in “The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz”, he claimed that the two musicians were the first to show up for the concert, and spontaneously performed the duets to entertain the waiting audience. Using the matrix numbers as a guide, Morgenstern placed the duets at the very end of the concert. Feather’s review contradicts both Williams and Morgenstern by stating that the Byas/Stewart duet was an “interlude” (we will assume that the British-born and educated Feather knew the proper use of that word). The Rosenkrantz memoir also makes it clear that Byas and Stewart had performed together before the concert, and Morgenstern states that Rosenkrantz recorded the duo in his apartment a few days before the concert. Everyone agrees that the concert started quite late, but did Norvo’s group play first because none of the other musicians had turned up? It seems likely, since Norvo’s band was onstage for  nearly an hour, playing a mixture of long jam session length tunes and standard ballads. In all, the concert went on for two hours and twenty minutes without an intermission, ending only when the stagehands pulled the curtain across the stage. Many of the later groups played 15-minute sets, and Coleman was apparently rushed off the stage after only one number owing to time constraints.

nearly an hour, playing a mixture of long jam session length tunes and standard ballads. In all, the concert went on for two hours and twenty minutes without an intermission, ending only when the stagehands pulled the curtain across the stage. Many of the later groups played 15-minute sets, and Coleman was apparently rushed off the stage after only one number owing to time constraints.

Any of the audience members attuned to bebop would have heard elements of the new music throughout the concert. Norvo’s opening selection was a piece called “One, Two, Three, Jump”, a variation on a “mop, mop” number, a riff-based melody with phrases ending on two strongly accented quarter notes on the same pitch. There were several of these pieces around in 1944 and 1945, including the Coleman Hawkins tune that gave the style its name (the record—produced by Feather—was also known as “Boff Boff”), Tiny Grimes’ “Red Cross” and Sir Charles Thompson’s “The Street Beat” (both recorded with Charlie Parker). In retrospect, we can see that the “mop, mop” figure was a simplified version of the eighth-note “be-bop” phrase endings from the Gillespie/Parker recordings. The youngest members of Norvo’s group, Shorty Rogers and Aaron Sachs, were both clearly aware of Parker and Gillespie, and there are occasional glimpses of bop style in their solos. The rest of Norvo’s band was equally aware of bebop: Palmieri played on the first Gillespie/Parker sessions for Guild (recorded in February, and as noted, already receiving  airplay from Symphony Sid), and the remaining members of the Norvo band (except Bert) recorded with Parker and Gillespie for Comet Records only 4 days before the Town Hall concert. Later in the concert, Billy Taylor played piano for both Bill Coleman and Stuff Smith, and his style reflected a mixture of Art Tatum’s fluidity and Nat Cole’s proto-bop harmony. Additionally, the Wilson/Phillips version of “I Can’t Believe That You’re In Love With Me” included one of the earliest examples of a bop staple, a series of four-bar exchanges between the drummer (Powell) and the other band members. Stuff Smith’s version of “Perdido” interpolated the “Wahoo” line adopted by boppers for their performances of the song.

airplay from Symphony Sid), and the remaining members of the Norvo band (except Bert) recorded with Parker and Gillespie for Comet Records only 4 days before the Town Hall concert. Later in the concert, Billy Taylor played piano for both Bill Coleman and Stuff Smith, and his style reflected a mixture of Art Tatum’s fluidity and Nat Cole’s proto-bop harmony. Additionally, the Wilson/Phillips version of “I Can’t Believe That You’re In Love With Me” included one of the earliest examples of a bop staple, a series of four-bar exchanges between the drummer (Powell) and the other band members. Stuff Smith’s version of “Perdido” interpolated the “Wahoo” line adopted by boppers for their performances of the song.

If the bop elements weren’t clear from the above performances, there was Don Byas’ brilliant harmonic explorations of “Indiana” and “I Got Rhythm” with Stewart (In his Metronome review, Feather gripes that the duo “didn’t seem to accomplish anything that wouldn’t have sounded better with a full rhythm section”, but Byas’ frequent use of extended harmony is especially vivid when cast against Stewart’s traditional bass lines.) After the duets, Wilson joined Byas and Stewart for a lovely version of the current pop hit, “Candy”. Byas’ lush solo was a prototype of modern tenor sax ballad style. At the end, Byas played an extended cadenza, but Wilson and Stewart seemed unsure of when to hit the final chord; instead, they played isolated chords when Byas clearly wanted to play unaccompanied.

Despite the chaos that surrounded the concert, the music stands up very well. Norvo’s xylophone solos on “The Man I Love” and “Ghost of a Chance” are superb, with the band offering an exciting send-off on the Gershwin standard. While the Norvo jams on “In a Mellotone”, “One Note Jive” and “Seven Come Eleven” have individual highpoints, they go on much too long. Feather claimed that Wilson and Coleman seemed uninspired at the concert, but the recordings show that both men were in prime form. Krupa’s trio played flashy arrangements, and the lack of a bass gave the group a hollow, empty sound. Smith’s trio (filled out by Ted Sturgis’ bass) swung mightily throughout their set, and it’s too bad that they didn’t have more time to play (Morgenstern claims that a fourth tune by Smith went unrecorded). There are at least two further unissued items from this concert: Sarah Vaughan performed Ellington’s “I Got It Bad” with Norvo’s band, and Fran Warren sang “Temptation” to the sole accompaniment of Powell’s “jungle-style” drums.

Despite the chaos that surrounded the concert, the music stands up very well. Norvo’s xylophone solos on “The Man I Love” and “Ghost of a Chance” are superb, with the band offering an exciting send-off on the Gershwin standard. While the Norvo jams on “In a Mellotone”, “One Note Jive” and “Seven Come Eleven” have individual highpoints, they go on much too long. Feather claimed that Wilson and Coleman seemed uninspired at the concert, but the recordings show that both men were in prime form. Krupa’s trio played flashy arrangements, and the lack of a bass gave the group a hollow, empty sound. Smith’s trio (filled out by Ted Sturgis’ bass) swung mightily throughout their set, and it’s too bad that they didn’t have more time to play (Morgenstern claims that a fourth tune by Smith went unrecorded). There are at least two further unissued items from this concert: Sarah Vaughan performed Ellington’s “I Got It Bad” with Norvo’s band, and Fran Warren sang “Temptation” to the sole accompaniment of Powell’s “jungle-style” drums.

The Town Hall concert is overdue for a full reissue. The last time that the entire concert was issued was as part of Mosaic’s 1990 “Complete Commodore Recordings”. I have not heard Mosaic’s transfers, but I trust that they matched their usual high standard. Every other reissue of this music that I’ve encountered seems to have some sort of technical issue. The 1973 Atlantic issue crams two hours of music onto two LPs. I have owned three copies of this set, and they all mis-track during Wilson’s piano solo on “I Can’t Believe”. However, the Atlantic also includes the complete version of Coleman’s “Stardust” (the Pair/Commodore CD unaccountably omits Taylor’s gorgeous piano solo) and it has a better transfer of “In A Mellotone” than the 1974 edition on London (which has a noticeable tempo sag midway through Palmieri’s solo). The concert fits very comfortably on two CDs, and if the unissued selections could be restored, it would be a superb documentation of this event, which captured a time just before jazz (and the world) lost its innocence.

Thanks to Aaron and Phyllis Sachs, Dan Morgenstern, Scott Wenzel, Joe Peterson, Robin Filipczak, Fradley Garner and Frank Büchmann-Møller for sharing memories and research.