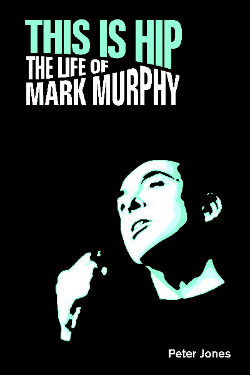

Superb artists deserve superb biographies—and Mark Murphy certainly deserves Peter Jones’ just published “This Is Hip: The Life of Mark Murphy” (Equinox). Meticulously researched, skillfully written, and filled with the recollections of scores of sources, Jones’ biography is admiring of its subject—yet not fawning. Jones is not afraid to criticize Murphy when the singer’s art is a tad too purple, or his behavior self-indulgent. Yet what comes through is a fearless risk-taker of an artist, living life for his art at the expense of creature comforts. With an exhaustive discography and two packed-with-further-information appendixes, This Is Hip takes no short-cuts. This fine book makes one want to hear Mark Murphy in all his glory.

Superb artists deserve superb biographies—and Mark Murphy certainly deserves Peter Jones’ just published “This Is Hip: The Life of Mark Murphy” (Equinox). Meticulously researched, skillfully written, and filled with the recollections of scores of sources, Jones’ biography is admiring of its subject—yet not fawning. Jones is not afraid to criticize Murphy when the singer’s art is a tad too purple, or his behavior self-indulgent. Yet what comes through is a fearless risk-taker of an artist, living life for his art at the expense of creature comforts. With an exhaustive discography and two packed-with-further-information appendixes, This Is Hip takes no short-cuts. This fine book makes one want to hear Mark Murphy in all his glory.

Born in 1932, Murphy grew up the third child of four in Fulton, New York. His father, Dwight Louis Murphy (nicknamed DL), was the opposite of his son. People loved DL’s openness and energy, always outdoors, holding parties for friends on his boat, writes Jones. But Mark found his dad intimidating, while DL found his son a source of embarrassment and frustration…(Mark) was so shy and sensitive at school that he would sometimes start sobbing uncontrollably in class… When Mark was 14, his Uncle Bill played him an Art Tatum record. Bitten by the jazz bug, emotionally connected to the music…Mark was performing in public by his second year at Fulton High School. Jones skillfully dives into the psyche of a young man, who already realized that he was gay, and who began to lose his hair early, wearing a series of wigs.

After studying drama at Syracuse University, Murphy moved to Greenwich Village, where people such as Sheila Jordan, Nat Hentoff, and Steve Allen encouraged the young singer. He met his idol, Peggy Lee, who attempted to seduce the shy young man. Signed by Decca Records, he recorded his first album, “Meet Mark Murphy” in June 1956. Jones is an astute critic: There was no question that (Murphy) had the chops. But there were also some signs of trouble to come. Here and there he makes the mistake of overdoing it. Again, Jones is no sycophant, but he realizes that his subject is a gifted, uncompromising artist: He knew that if as a jazz singer you wanted to scale the heights of performance, you had to take risks, and that meant that consistency was not always possible.

As besotted with Beat writer Jack Kerouac as he was with Miles Davis, Nat Cole and Peggy Lee, Murphy’s life became an endless world-hopping adventure—living in London for several years in the 1960s, performing all over Europe and in South America. It was in London that Murphy met the love of his life, Eddie O’Sullivan. Soon the two shared a flat. Writes Jones: [Murphy] remained discreet about his sexuality. Despite knowing Mark for 40 years, [friend] Michael Bourne was surprised when he learned of Eddie’s existence for the first time at Mark’s memorial service in 2016. Jones is skilled at cataloging Murphy’s endless professional disappointments: low album sales, bad financial deals, and endless travel. Jones quotes a friend: For his entire life, Mark was struggling financially. I don’t think he ever had any appreciable money at all. For many years, the singer lived in a camper and on friends’ couches.

Yet Murphy’s endless artistic persistence paid off. By the 1970s he taught at various European universities, filled clubs all over the globe, was nominated for (but never winning) Grammy awards, and worshiped by a new generation of jazz singers, including Kurt Elling. At this time, the International Mark Murphy Appreciation Society, with its own newsletter, “Mark’s Times”, was established in the U.K. In addition to contributions from fans all over the works, Murphy also sent in correspondence from the road and from home. Murphy remained a restless figure: “Mark was always changing his appearance,” with friends at times not even recognizing the singer. After the death of O’Sullivan, Murphy began to drink heavily, even dabbling with crack cocaine. Sadly, there is a price to pay for being a fearless artistic pioneer.

Above all, however, Jones makes it clear what a truly unique, uncompromising and gifted artist Murphy was. A constant theme of [the] book [is] why Mark Murphy never quite emerged into mainstream consciousness, despite a career spanning seven decades. To put it bluntly, most people have never heard of him. The qualities that set Mark Murphy apart from any other singer were those that simultaneously made him both a great artist and a commercial failure. He did not popularize his art. His unpredictability, his unwillingness to compromise in the struggle between art and entertainment, was the thing that condemned him to obscurity, but also the thing that made him great. Further, Jones helps the Murphy neophyte by recommending the singer’s best albums: “Mark Murphy Sings” (“one of the greatest jazz vocal albums in history”); “Stolen Moments“; “Bop For Kerouac“; “Brazil Song“; and “Once To Every Heart“. Perhaps with a biography this fine, this honest, and this carefully researched, Mark Murphy will reach the wider audience that eluded him in his lifetime.

Want some solid advice? Buy yourself any (or all!) of the albums listed above and Peter Jones’ This Is Hip—and enrich your life.