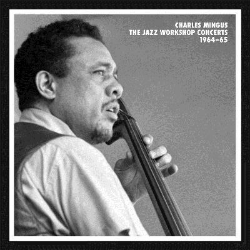

Charles Mingus was quite critical of avant-garde jazz musicians of the mid-1960s. On one of his stage announcements in the new Mosaic set “The Jazz Workshop Concerts”, he chides the free players for claiming that “they closed the book on [bebop] when most of them still can’t play Bird”. Yet in his music, Mingus provided the ideal bridge over this chasm of musical styles. He was firmly rooted in tradition, but he was eager to expand the existing forms into new directions. While he produced fascinating music throughout his career, his greatest body of work comes from the decade spanning 1955-1965. The Mosaic 7-CD collection focuses on the final two years of this period with five concert performances originally scheduled for issue on Mingus’ own record label. Over two hours of this music has not been released until now (In fact, the set was originally scheduled for release this past June, but at the last minute, Mosaic found additional unreleased material from three of the five concerts and they revamped the set to include it all. Gotta love that kind of dedication!).

Charles Mingus was quite critical of avant-garde jazz musicians of the mid-1960s. On one of his stage announcements in the new Mosaic set “The Jazz Workshop Concerts”, he chides the free players for claiming that “they closed the book on [bebop] when most of them still can’t play Bird”. Yet in his music, Mingus provided the ideal bridge over this chasm of musical styles. He was firmly rooted in tradition, but he was eager to expand the existing forms into new directions. While he produced fascinating music throughout his career, his greatest body of work comes from the decade spanning 1955-1965. The Mosaic 7-CD collection focuses on the final two years of this period with five concert performances originally scheduled for issue on Mingus’ own record label. Over two hours of this music has not been released until now (In fact, the set was originally scheduled for release this past June, but at the last minute, Mosaic found additional unreleased material from three of the five concerts and they revamped the set to include it all. Gotta love that kind of dedication!).

Mosaic’s set includes the Town Hall concert from April 4, 1964, a concert from Amsterdam recorded six days later, performances from the Monterey Jazz Festivals of 1964 and 1965, and the “My Favorite Quintet” Minneapolis concert of May 13, 1965. On the first two concerts, Mingus leads one of his greatest bands with Johnny Coles on trumpet, Clifford Jordan on tenor, Eric Dolphy on flute, bass clarinet and alto, Jaki Byard on piano and Dannie Richmond on drums. Mingus and Richmond could swing anyone into bad health and their powerful rhythmic feel electrifies this music throughout. Byard could play any style from stride to free, and Mingus had Byard open these two concerts with his unaccompanied multi-stylistic (and apparently thorough-composed) tribute to Art Tatum and Fats Waller, “A.T.F.W.” Of the horn men, Coles was the most traditional and Dolphy the most daring; Jordan was stylistically in the middle, but Mingus and Richmond could effectively push him into the outer reaches, and his solos are quite surprising as a result. However, Mingus challenged all of these players: Coles moves outside the changes on several occasions, and Dolphy plays some of his most lyric flute on the Town Hall version of “Meditations on Integration” (listed here and on the original issue as “Praying with Eric”).

Mingus’ music seemed to be in a constant state of evolution, and it is fascinating to hear how the same piece changed between concerts. There are three different versions of “Meditations on Integration” on this set, and on each version, major sections of the composition are shifted from one place to the other. Each of these renditions have their own strengths, so trying to pick one as a favorite is as useless as trying to pick a favorite flavor of ice cream. Mingus liked to teach his music aurally, and as a result, the concepts developed for one composition could easily turn up in another piece. For example, some of the background ideas from Town Hall’s “So Long Eric” appear in the Amsterdam version of “Parkeriana”. Brian Priestley’s superb liner notes help the listener sort out the lineage of the ideas through Mingus’ other recordings, but even he fails to note that the vocalized argument between Dolphy and Mingus that first appeared on “What Love” from “Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus” shows up here on the Town Hall version of “Fables of Faubus” (but not on the longer, completely different and totally fascinating Amsterdam version).

The final three concerts were recorded after Dolphy’s death, but while Mingus could hardly replace the progressive reed man, his groups still effectively advanced his musical philosophy and style. For the 1964 Monterey concert, the front line featured Lonnie Hillyer, who was a more progressive trumpeter than Coles, and the saxophones of Charles McPherson and John Handy, both of whom balanced their styles between bop and free. After an energetic Ellington medley and a so-so version of “Orange Was the Color of her Dress, then Blue Silk”, the band was expanded to 12 pieces for a newly orchestrated and superbly played version of “Meditations”. The concert was lauded as one of Mingus’ greatest triumphs and it still holds up well, despite some major distortion on the recording. When Mingus returned to Monterey the next year, he had a stack of new music for his octet to premiere, but his stage time was severely cut by the festival promoters. Two of the four pieces they played that afternoon are newly released in this set, but the playing is quite ragged and the performance ends just as it starts to gain momentum. The Minneapolis concert with Hillyer and McPherson in the front line is much better, and the 68 minutes of unreleased music features a formerly unknown piece called “A Lonely Day in Selma, Alabama” (dedicated to the civil rights tragedy from two months earlier) and a rarely heard barn burner here called “Copa City Titty” and formerly known as “O.P. Junior”. There is also a stunning piece called “Bird Preamble” which re-works some of the ideas of “Parkeriana”, and an untitled blues that features Hillyer and Mingus in the same kind of vocalized argument that the bassist and Dolphy had done on “What Love”.

Mingus was considerably less successful as a record company executive than as an artist. The albums he produced were sold only through mail order, and were manufactured in limited runs. There were complaints from customers who had sent money but never received their records, and Mingus seemed unable to have the albums available for sale at his concerts. Although some of this music was later reissued by Fantasy and Prestige, it never seemed to get the exposure it deserved. Mosaic’s set fills this gap in Mingus’ discography and adds several new important recordings to the canon. It does not pretend to cover all of the music from this period, and listeners intrigued by this music should also pick up the Jazz Icons DVD, “Charles Mingus Live in ‘64” as well as the authorized concert recordings available on Sue Mingus Music/Sunnyside and Revenge. Mingus’ music is powerful and inspiring, and it provides vibrant proof of jazz as a living art.