Duke Ellington was far from a typical Christian. He swore, smoked and drank; he collected royalties for music he did not compose, and he was a serial adulterer. However, Ellington’s belief in God stemmed back to his early childhood, when he attended prim Methodist services with his mother, and roof-raising Baptist meetings with his father. Clearly, the differences between the two forms of worship caught the boy’s attention, and he found ways to embrace both in his personal religious philosophy. Ellington could emulate the boisterous Baptist feeling in his music—even when the scene was not specifically religious. Whenever an interviewer would ask about his rise to fame, Ellington would inevitably say that when he was a little boy, his mother told him he was blessed, and that he had nothing to worry about. The late hours of a bandleader precluded Ellington’s attendance at Sunday morning services, but he kept a Bible with him wherever he went, and when his mother died in 1935, he read the holy book from cover to cover to assuage his grief.

Any doubts as to Ellington’s deep and sincere faith can be dissipated through a single pivotal composition. “Come Sunday” was written as the spiritual in Ellington’s musical history of the American Negro, “Black, Brown and Beige”. The unquestionable strength of the melody, along with the reverent lyrics added years later, revealed Ellington’s fervent belief in a higher being, and his earnest desire to communicate that faith through his music. While “Black, Brown and Beige” received mixed reviews on its 1943 Carnegie Hall premiere, Ellington refused to let go of his masterpiece. In addition to the Carnegie recording—issued in 1977, three years after Ellington’s death—Ellington recorded versions of “Black, Brown and Beige” in 1944, 1958 and 1965 (the latter also released posthumously). Each recording featured several changes from the original score, but “Come Sunday” was always a prominent part of the suite. [Years later, Ellington’s paramour, Fernande, and his son, Mercer, were discussing Ellington’s music while the maestro was sitting in the same room editing music. Fernandae remarked that “Come Sunday” was “the single most beautiful piece of music [Duke] ever wrote”. Mercer looked at his father, who simply said “She’s right” and went back to work.]

It was the 1958 recording of “Black, Brown and Beige” featuring Mahalia Jackson’s stunning rendition of “Come Sunday” which attracted the attention of two San Francisco clergymen, Rev. C. Julian Bartlett and Rev. John S. Yaryan—the latter the canon of Grace Cathedral. Bartlett and Yaryan both wrote letters to Ellington, encouraging him to create a concert of sacred music for Grace Cathedral. Initially, Ellington refused the commission, stating When you get that kind of invitation, you’re not in show business. You think to yourself “It has to be kind of right. You have to go out there and make a noise that tells the truth.” I had to stop and figure out my eligibility. I prayed. Eventually, Ellington was told (or reminded of) the story of the man who was criticized for juggling before a statue of the Virgin Mary. The performer replied that he was doing the skill he did best as an offering to God. Ellington later expanded on the topic: I believe that no matter how highly skilled a drummer or saxophonist might be, if this is the thing he does best, and he offers it sincerely from the heart in—or as accompaniment to—his worship, he will not be unacceptable because of lack of skill or of the instrument upon which he makes his demonstration, be it pipe or tom-tom. Clearly, Ellington found the similarity between the juggler and himself, and he eventually agreed to perform the concert.

The term “sacred concert” seemed to suit Ellington. As his personal religious philosophy reflected the moral tenets of Christianity, rather than the dogma of particular denominations, Ellington had no interest in creating a “jazz mass” (a form that was popular in the 1960s in the light of the Vatican’s relaxed regulations about music in the church). Billed as a “sacred concert”, Ellington had free reign to present any music with a sacred theme. He assured his benefactors and audience that the performance would not include a jam session, and that none of Ellington’s hit pop songs would be included in the program.

The Grace Cathedral concert was scheduled for September 16, 1965, as part of the Cathedral’s year-long celebration of its consecration. Preparations went on for about two years, but the always-busy Ellington wasn’t making much progress on the music. One night, he made a cross-country phone call to his composing assistant, Billy Strayhorn. Ellington said he wanted to set the first four words of the Bible—“In the Beginning, God”—but wasn’t sure of how to do it. After assuring Ellington that he was much more skilled at setting text, Strayhorn agreed to try his own setting. According to Ellington, the resulting two versions of the six-note phrase both started and ended with the same pitches, and only two of the notes were slightly different. Ellington never revealed if the final version of the motive was his, Strayhorn’s or a combination of both, but the motive appears throughout “In the Beginning, God”. The first concert also included an original song called “Tell Me It’s the Truth” and a new setting of “The Lord’s Prayer”. For the rest, Ellington revived music from earlier projects, including the solo piano work, “New World A-Comin’”, four songs from his 1963 Chicago stage production, “My People”, as well as “Come Sunday” (which had also appeared in “My People”). The latter appears three times in the program: first as a vocal solo, then as a feature for Johnny Hodges, and finally in a long-meter up-tempo version re-titled “David Danced Before the Lord” featuring the tap-dancing of Bunny Briggs.

In the Sacred Concerts, Ellington had a message to deliver and he didn’t want to alienate any potential listeners. Ellington’s fan base included long-standing jazz aficionados, casual pop music lovers, and some who simply enjoying hearing his colorful stage patter. All of these people needed to be represented in Ellington’s sacred music, as well as the people who had never heard the Ellington band live, but might attend the concert out of curiosity. As a result, the music and lyrics of the Sacred Concerts move from the lofty to the commonplace with stunning frequency. At times, simplicity and complexity appear simultaneously, but more often, Ellington either hammers home a point with a sung sermonette, or leaves the audience awestruck at the mysteries of his harmonic language. Most of all, Ellington delivers a positive message, filled with sentiments about love, hope and freedom, and avoiding references to “miserable sinners who are all going to Hell”. Ellington’s original lyrics have been widely criticized as naïve (and some are actually cringe-inducing) but Ellington was well-aware of the breadth of his audience and he knew that his lyrics had to speak to many people. As Ellington stated, Every man prays in his own language, and there is no language God doesn’t understand.

September 16, 1965.

“In the Beginning, God” was the most substantial part of the First Sacred Concert, both in its overall scope, as well as its 20-minute playing time. In this piece, Ellington introduces many of the band’s soloists, adds guest vocalists, offers dramatic flourishes for the orchestra, and displays his dry and knowing wit. The official recording of the First Sacred Concert took place at New York’s Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church on December 26, 1965. The audio recording was made and issued by RCA Victor, and the concert was also filmed by either NBC or CBS for a national broadcast in January 1966 (Unfortunately, the video was not available for review here, but the audio recording was remastered for RCA’s “Duke Ellington Centennial” box set. ) “In the Beginning, God” is the first track on the LP, and this version has been the model for many re-creations of the work. It opens with the rhythm section playing in a somewhat menacing manner as Ellington introduces the main motive at the piano. It is a diatonic line made difficult by its successive leaps of a minor third, a major sixth, and a minor sixth and its overall range of a major tenth. Harry Carney intones the motive again through his deeply resonant baritone sax, as Ellington provides the sole accompaniment on piano. The band comes in at a medium-slow tempo as Carney continues to improvise, but everything is interrupted with a dramatic high clarinet note from Jimmy Hamilton. He plays a brief cadenza before the trombones, Carney and the rhythm section re-enter. Another Hamilton cadenza leads into the vocal, sung here by Brock Peters. He sings the motive with great passion and hints at what is to come with the sung passage “No Heaven, No Earth, No Nothing.” The tempo suddenly picks up at a quick tempo as Peters continues singing. Then, as Ellington plays behind him, Peters launches into a spoken passage noting all of the things that didn’t exist: No night, no day, no bills to pay…No birds, no bees, no Beatles and my personal favorite, No symphony, no jive, no Gemini Five, no 10, 9, 6 or 8, no men trying to fill an inside straight (The audience didn’t seem ready for jokes in church, which is surprising since most ministers regularly spice up their sermons with a few punch lines). The first part of the piece ends back in the slow tempo with Peters singing the final high note—fittingly, on the word “God”—at full voice.

The remaining 12 minutes of “In the Beginning, God” is given over to the soloists. Tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves improvises over a gospel-styled background, as the choir enters chanting the names of the Old Testament books and the band riffs joyfully (and joyful it is, as the band quotes a lick from Ellington’s “Jump for Joy”!) After a Gonsalves cadenza, there is a fanfare to introduce trumpeter Cat Anderson, who intones the main motive at successively higher pitch levels. At the end of his spot, Anderson squeaks out the highest notes which he—or anyone else—could play on a standard trumpet. Ellington follows with the spoken quip “That’s as high as WE go!” Then under a Louis Bellson snare drum roll, the choir chants again, this time the books of the New Testament, with Ellington plucking out ascending notes from the keyboard. As the choir nears the end of the list, the tempo speeds up, and Bellson plays an impressive 5-minute drum solo, starting with cymbals and eventually moving to the tom-toms. The solo ends with more cymbals, a final sung declaration by the choir and a final band chord.

Video recordings of the first performance at Grace Cathedral and a 1966 performance at Coventry Cathedral in England show that Ellington made major revisions to this work after the premiere. The Grace version starts with the vocal (sung here by Jon Hendricks), then to the Gonsalves section (which includes a solo break that seemed to take the saxophonist by surprise). Gonsalves continued to solo after the choir finishes chanting. Cat Anderson’s feature follows (minus the closing joke from Ellington), the choir’s New Testament chant is next (without Ellington’s ascending melody), the drum solo is omitted, and the ensemble jumps to the final choir declamation and the closing chord. By the time of the Coventry concert in February 1966, Ellington had added a lyric section in lush harmony for the chorus—based on “The Word Made Flesh” and located right before Anderson’s spot—as well as a fugal variation which followed the reinstated drum solo (now played by Sam Woodyard). Additionally, the solo baritone part—sung here by the rather stiff George Webb—moves the initial “no heaven…hell…nothing” lyric to the up-tempo section.

“Tell Me it’s the Truth” is a gospel waltz. In San Francisco and New York, the arrangement opens with a spirited duet between trombonist Lawrence Brown and alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges. Gospel singer Esther Marrow sings the vocal whose lyric consists of the title line, the expansion “the gospel truth” and the final line, “’cause the truth is the light, and the light is bright, and that’s right. Right? Right!” Marrow looks extremely nervous on the Grace video, and she doesn’t sound much more relaxed on the New York recording. She barely gets the song out, and she seems completely unable to entice the audience to respond to the repeated words at the end of the chorus. Marrow was not with the band when they traveled to Coventry, so the piece became an instrumental feature for Brown and Hodges. “The Lord’s Prayer”, set over a driving beat, was obviously inspired by Mahalia Jackson. In hearing this piece, one can easily imagine Jackson raising the roof—and not stopping until everyone in the church had been converted. Unfortunately, Marrow lacked any of the charisma that Jackson had in reserve. Her voice is strong, but her facial expression is blank on the Grace video. In New York, Ellington tried to add some life to her performance by having trumpeter Cootie Williams growl incessantly in response to her vocals. It helped, but not too much. The piece was not performed at Coventry.

“New World A-Comin’” was premiered in December 1943 as a concerto for Ellington and his Orchestra. In later years, Ellington used it as a solo piece, and its presence in the First Sacred Concert may have been a method to pad the program. The RCA Ellington box includes two versions, one from each of the two concerts performed that December night in New York (the takes were not attached to the concerts, so we don’t know if the master is from the first or second concert). The master take was probably chosen for its greater energy, but the alternate finds Ellington using a lighter touch to greater effect. Yet, both the Grace and Coventry are the best extant performances due to Ellington’s superb use of dynamics. (Only part of the Coventry performance made it to the videotape, but the entire performance can be heard on Storyville’s CD “Duke Ellington at Coventry”, which contains the full soundtrack of the concert.)

The four songs from “My People” (not counting “Come Sunday”, which will be discussed below) were all recorded at the New York concerts, but only two of them were included on the original Sacred Concert LP. “Ain’t But the One” was the standout of these songs. With a directness to its music, and lyrics reminiscent of gospel, folk and rock music, this powerful swinger brought the raw emotion of the black church to the predominantly white audience. The New York performance with soloist Jimmy McPhail and the Herman McCoy Choir is an emotionally overwhelming experience with spirited call and response patterns in the voices alongside potent riffing by the horns. McPhail had been part of the Ellington musical family since at least 1950, but he was never featured as effectively as here, where he unleashes his inner preacher. “Will You Be There?” is a declamatory piece for the choir and soloist, which was probably tacked onto “Ain’t But the One” because of its church origins. “99 Percent Won’t Do” continues in the evangelical style, but the performance is marred by pallid rhythm and low energy in the chorus. “Heritage” (re-titled “My Mother, My Father and Love”) is another flawed rendition of a worthy piece. It is Ellington’s heartfelt tribute to his family—and as he notes in the spoken introduction, none of the family members are referred to in the past tense. The version on Storyville’s re-creation of the complete “My People” score is much better than this hesitant recording.

I suspect that Ellington made Esther Marrow study Mahalia Jackson’s recording of “Come Sunday”, and the results are obvious on the Grace and Fifth Avenue recordings. She puts her heart and emotions into this beautiful combination of music and lyrics, and gives the compelling performance which should have marked all of her work. Ellington did not always pick the best vocalists for his band, and it seems that Ms. Marrow was simply in over her head. She didn’t stay long in the Ellington world, but “Come Sunday” redeems her to some degree. The instrumental version of “Come Sunday” uses some of the development material from “Black, Brown & Beige” (one section is rescored with Jimmy Hamilton’s clarinet replacing Ray Nance’s violin from the original). Naturally, the highlight is Johnny Hodges’ stunning solo performance over sustained chords (Both the New York and Coventry performances are equally mesmerizing). Long before “Come Sunday” had lyrics, Hodges sang this tune through his horn. I can’t help but imagine that Ellington found the words to this song by listening to his star saxophonist glide through its glorious melody.

While the order of selections was shuffled around in performances of the First Sacred Concert, “David Danced Before the Lord” always remained the closer. The sight of Bunny Briggs tap-dancing before the altar of Grace Cathedral raised more than a few eyebrows, but the passion of the performance certainly made up for any supposed improprieties. The Grace version is a delight from beginning to end, with Briggs displaying boundless energy throughout, Jon Hendricks adding a fine scat solo, and Louis Bellson giving Briggs a suitable challenge near the end. Herman McCoy’s choir lacks polish on the RCA recording and Hendricks’ absence is certainly felt. However, the interplay between Ellington and Hamilton (in the spot where Hendricks sang at Grace) and the powerful closing band chorus makes the track a partial success at the very least.

The loose programming of the Sacred Concerts allowed Ellington to add music featuring the band, choir or guest artists. The Grace Cathedral Choir performed several traditional spirituals including “Do You Call That Religion?”, “My Lord, What a Morning”, “Every Time I Feel the Spirit” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”. Vocalist Toney Watkins—usually associated with Ellington’s Second and Third Sacred Concerts—made his debut with the band at Grace singing “The Preacher’s Song”, an a cappella slow-tempo setting of “The Lord’s Prayer” performed at the end of the concert. At the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in New York, Billy Strayhorn presented a new song “A Christmas Surprise” which was performed by Lena Horne, with the composer at the piano. RCA recorded both performances of this charming song, but neither was issued until the release of the Ellington Centennial box in 1999. The Storyville CD of the Coventry performance contained a genuine surprise with its inclusion of “Come Easter”, a relaxed and understated instrumental which opens with the trombone trio and gradually adds Carney, Hamilton, and the trumpets. Unfortunately, the piece ends just as it gains momentum. The band read through the piece on the day of the concert, made this concert recording, and never recorded it again.

Ellington’s goal to reach a wide variety of listeners was certainly reached in San Francisco, where one report stated that the congregation included a wild mixture of jazz musicians up from the Monterey [Jazz] Festival, a few bearded hipsters, matrons, students, and the great well-dressed mass of Ellington lovers. Most of the Bay Area critics wrote positive notices, including Ralph J. Gleason (who also filmed the concert for educational TV). Gleason was entranced by the music, but noted a problem that plagued many of these concerts: the poor amplification systems which usually allowed those in the cheap, distant seats to hear the music better than those in the expensive, close chairs. In a Downbeat review of the New York performance, Dan Morgenstern praised Ellington’s use of the term “sacred concert”, expanding that In spirit and content, the music is more fitting and proper to a religious context than pieces with more ambitious titles. Unfortunately, some conservative commentators did not agree. A Sunday school teacher from Baltimore wrote that true worship and prayer is not accomplished through the medium of jazz, but through the teaching of God’s word. A reader of the “Des Moines Register” asserted that Ellington’s music did not promote worship, but was simply a ploy to have fun shocking a few old fuddy-duddies. Surprisingly, Black churches were slow to accept Ellington’s sacred music. It would be nearly nine months after the premiere before Ellington performed this music at a black church, specifically the Brooklyn First AME Zion Church. And while there were three more performances in 1966 of the sacred concert in black churches, a December performance in Washington DC was nearly sabotaged due to the objections of the primarily black Baptist Ministers Conference. The concert, held at Constitution Hall, was designed to be a charity event, but due to the furor in the local press, the auditorium was only two-thirds full for the performance. Thankfully, many churches—white and black—realized the value of Ellington’s music and the importance of embracing new methods of worship. From 1965 to the end of his life, Ellington received many requests for performances of the Sacred Concerts.

Billy Strayhorn was diagnosed with cancer of the esophagus in early 1964. Even under the supervision of Ellington’s personal physician, Arthur Logan, his health went on a downward spiral. His appearance with Lena Horne at the First Sacred Concert in December 1965 was the last time he played in public. Ellington couldn’t stand to see Strayhorn in the hospital, but called him on the phone every day. Moreover, he encouraged Strayhorn to continue writing for the band. Strayhorn’s emotionally wrenching “Blood Count” was sent to the band from the hospital. It would be his final composition. When Strayhorn died on May 31, 1967, Ellington was on the road in Reno. He rushed back to New York for Strayhorn’s funeral, and wrote an eloquent tribute to his friend which included Strayhorn’s Four Freedoms, a set of moral codes which found a place in Ellington’s Second Sacred Concert. Strayhorn’s passing was an obvious sign to Ellington about his own mortality, and without anyone to take Strayhorn’s place, Ellington knew that he was the only one to write new music for the band. Ellington recorded a tribute album to Strayhorn in September 1967—the extraordinary “…And His Mother Called Him Bill”—and then he set to work writing an entirely original set of new sacred music.

No one could replace Strayhorn, of course, but Ellington built his Second Sacred Concert around the talents of a superb musician who would give new voice to his music. That musician was the vocalist Alice Babs. For those who may be unaware of her, Babs could be considered the Swedish version of Julie Andrews. Like Andrews, Babs first caught the public’s attention as a teenager, she was blessed with an astounding voice and a wide vocal range, and she promoted her sunny and optimistic demeanor through a series of film, radio and television appearances. She performed and recorded classical works, folk songs and pop music, but Babs’ greatest talent was as a jazz singer. She had unerring pitch, perfect English diction, and was an outstanding scat singer. Ellington could put any music in front of her, and she would sight-read it without error. The two first met in February 1963, when Ellington was booked to film a television show in Sweden. The producers wanted to have a local singer perform with the Ellington band, so they handed Ellington a pile of records by leading Swedish artists for him to audition. All it took was a quick listen to Babs’ 1959 LP “Alice and Wonderband” for Ellington to make his decision. Once the special was completed, Ellington told Babs, “We should make a record together”. Babs was flattered at the offer—she had been an Ellington fan since she was 12 years old—but was completely surprised when Ellington called three weeks later, asking her to fly to Paris in the coming days to record. The resulting album, “Serenade to Sweden” was a rewarding collaboration highlighted by Babs’ exquisite version of “Come Sunday”. Perhaps the memory of that rendition convinced Ellington to hire her to sing his new sacred music. While Babs performed the Second and Third Sacred Concerts many times, she was unable to tour extensively with the band, owing to her own career and family commitments. When she wasn’t available, Ellington said he had to hire three vocalists to take her place.

Babs flew to New York in mid-January 1968 for four days of extended rehearsals, two concert performances, and the official recording of the Second Sacred Concert. Ellington had composed 90 minutes of new music in just about four months, and only he knew the way the music was to be assembled. Babs, the band, and choirs from AME Mother Zion Church, St. Hilda’s and St. Hugh’s schools rehearsed in a large room in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. For the first concert, the ensemble simply moved to the sanctuary of the church, where an overflow crowd of 6000 people and a TV crew awaited the new music. Ellington’s close friend Stanley Dance reports that the second performance at St. Mark’s in New Canaan, CT was much better since it was in a smaller church with better acoustics and no TV lights. Ellington had anticipated the acoustical issues at St. John’s, and thus rented engineer Robert Fine’s studio at New York’s Great Northern Hotel to create the official recording. The order of recording was shuffled to accommodate Babs’ schedule, and the full recording was later issued as a 2-LP set on Fantasy Records. When the RCA’s Ellington Centennial box was assembled in 1999, the box’s producer Orrin Keepnews, convinced his previous bosses at Fantasy to license the recordings of the Second Sacred Concert to RCA (which recorded the First and Third Concerts). Thus, all three of the Sacred Concerts were made available complete on CD for the first—and possibly only—time.

As with the first and third concerts, Harry Carney is entrusted with the first statement of the Second Sacred Concert’s primary theme. “Praise God” is a fairly short opener, but its majestic demeanor and performance underscores its importance. “Supreme Being” acts as the equivalent to the opening section of “In the Beginning, God”. Ellington said that the piece depicted the scene before, during and after the creation of order, and indeed, the music is so descriptive it nearly sounds like a ballet score. Babs was particularly impressed with this piece stating that Europeans, the conductors, people in the symphony orchestras will greatly admire this work. It belongs in the world of serious classical music. That is certainly true of the outer segments of this 12-minute work, but the central spoken part, intoned by the choir and soloists sounds like something from a church pageant. The humor that was an important element of the spoken portions of “In the Beginning, God” is completely absent. The only light-hearted part of this section is “The Apple”, a scene from the Garden of Eden, which was typically spoken by a young boy. However, the boy on the Fantasy recording seems rushed, and unaware of the underlying humor. Hamilton is featured on clarinet through the instrumental portions of the work (Hamilton’s role would be taken by Harold Ashby after Hamilton’s retirement later in 1968).

“Heaven” is one of the enduring songs from the Second Sacred Concert, and it is a prime example of an Ellington song that works simultaneously on two different levels. The first half of the melody is highly chromatic, opening with an ascending minor second, followed almost immediately by a descending minor seventh. In the next phrase, a descending major second is followed by an ascending minor second and a tritone. After two times through that obstacle course, the melody becomes fairly logical with relatively simple melodic movement. Taken on its own, it is simply a difficult song for Babs; but when paired with the lyrics, we see how the melody compliments the words. The opening section carries the following lyrics: Heaven, my dream/Heaven, divine/Heaven, supreme/Heaven combines…, which describes Heaven in terms which make it sound inaccessible. But what does Heaven combine? The rest of the lyric: Every sweet and pretty thing/life would like to bring/Heavenly Heaven to me/is just the ultimate degree to be. As the melody settles down, the lyric shows that Heaven contains things that we want to be around, and that as “the ultimate degree to be”, it is indeed a place for everyone. This was Babs’ first feature in this concert. Her opening chorus shows her astounding vocal control and winning delivery. Johnny Hodges’ creamy alto takes over, and he caresses the melody just as he had in Strayhorn ballads like “Isfahan”, “Passion Flower” and “Blood Count”. When Babs returns, the band adopts an attractive beguine feel for a chorus. In the final cadenza, Babs dazzles with her clear swoop into the high register.

Ellington switches to electric piano for “Somethin’ ‘Bout Believin’”, a choir feature with a relaxed opening reminiscent of Strayhorn’s “Charpoy” (aka “Lana Turner”). The words match the music well, as they describe the satisfaction of having faith in one’s life. There are a few lines spoken by the choir, and as they are set over harmonies which have already supported Ellington’s melody, the change from sung text to spoken seems unnecessary. One of the spoken parts denies the then-popular saying “God is Dead”, but for the most part, this is an amiable but not deathless portion of the concert. [Two things which should be considered regarding the choral music in the sacred concerts: Ellington deliberately made the choir settings easy, as he never knew the abilities of the church choirs with which he worked; also, as this music predated the emergence of college vocal jazz ensembles, most of the church choirs did not know how to sing in the jazz style. Ellington usually sent an assistant two weeks ahead to teach the choirs how to sing the music in the proper style.]

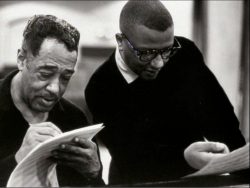

Despite its title, “Almighty God” is actually about God’s angels. After telling us about the angels that will make all of Heaven’s inhabitants comfortable, the bridge starts with the seemingly abominable line Wash your face and hands/and heart and soul/’cause you wash so well. Those who groan at the thought of another “Cleanliness is next to Godliness” bromide will likely miss the payoff: God will keep you safely/where there’s no sulphur smell. Even with this clever joke, this piece might be a little hard for a non-believer to take, but Babs is the perfect communicator. She sings the melody with total conviction, and later—accompanied first by Russell Procope’s clarinet and then by the choir—she provides elegant improvised fills in her upper register. From heavenly angels, Ellington then salutes an angel on Earth, the Reverend John Gensel, a Lutheran minister from New York who used personal and church resources to help needy jazz musicians (Gensel is pictured with Ellington at the top of this article). The full title of Ellington’s tone portrait is “The Shepherd Who Watches over the Night Flock” and it was one of the last features Ellington wrote for Cootie Williams. The trumpeter offers brilliant demonstrations of his legendary growl and open horn techniques, while constructing a passionate portrayal of Father Gensel.

The Second Sacred Concert was a product of the 1960s, and the eleven-minute “It’s Freedom” suite—with its constant reiteration of the principal word—is a concept that gets old rather quickly. However, there are some catchy melodies, good solos by the band and valid points in the lyrics. One section, subtitled “Sweet, Fat and That” was based on a piano lick by Willie “The Lion” Smith, but the words sound like a commercial: Freedom is sweet/on the beat/Freedom is sweet/to the reet complete/It’s got zestness and bestness/no more pains/no more chains/to keep me from being free/Freedom is sweet, fat/and that’s for me. After this light-hearted episode, Ellington has members of the choir say the word “freedom” in 17 different languages, and then Ellington salutes his late composing partner by reciting Billy Strayhorn’s four freedoms: freedom from hate unconditionally, freedom from self-pity, freedom from fear of possibly doing something that might benefit someone else more than it would him, and freedom from the kind of pride that could make a man feel that he was better than his brother.

Ellington follows the “Freedom” suite with a “Meditation” for piano and bass, which he also performed later in 1968 on a televised memorial to Robert F. Kennedy. Ellington’s abilities as a pianist were frequently overlooked, but here he is in top form, playing a piece designed to calm, not amaze. “The Biggest and Busiest Intersection” is an instrumental which Ellington prefaced with a lengthy monologue about choosing the proper road—in this case, the road to Heaven. The orchestration is impressive and highly descriptive in his emulation of road traffic. Live performances of this piece were show-stoppers with their inclusion of a lengthy Rufus Jones drum solo. The following piece was also a show-stopper in a different sense. “TGTT” stood for “Too Good to Title” and this remarkable vocal/piano duet was Ellington’s way of portraying Jesus Christ. Babs sings the angular, wordless melody with ease (she reportedly sight-read it perfectly at the first rehearsal) and the angelic quality of her voice is a perfect match with Ellington’s piano.

The title of Toney Watkins’ feature “Don’t Get Down on Your Knees to Pray until You Have Forgiven Everyone” is a favorite target of critics who dislike the Sacred Concerts. Yes, it’s very preachy…but this is actually a sermon! The Fantasy recording seems lifeless, and that makes it easier to hit it with brickbats, but its importance becomes apparent in the video recordings discussed below. “Father Forgive” continues Watkins’ feature. It is similar to the Prayers of the People offered weekly in many churches. The choir sings a repeated phrase, which is set against Watkins’ spoken pronouncements of everyday sins. At the end, the choir sings a lyric, contrapuntal passage in four-part harmony.

The concert closes with “Praise God and Dance”, based lyrically on the 150th Psalm and musically on Ellington’s opening movement. It opens with rubato statements of the Psalm by Babs and Ellington. This section stops and starts several times, and it just goes on too long before exploding into the closing fast tempo (yes, there is such a thing as too much Alice Babs!) The finale brings back many of the band’s soloists, but the choir’s repeated spoken exultations to “Praise God and Dance” seem empty without the visual element (to be discussed below). Still, the complex instrumental motives are well-played, and the solos by Paul Gonsalves, Cat Anderson and Buster Cooper bring the recording to a thrilling conclusion.

As implied above, the video recordings of the Second Sacred Concert are superior to the official audio version. Both versions were filmed in the fall of 1969, which meant the musicians had a better grasp of the music, as they had been playing it live for several months. Further, the visual aspect gives us important details that cannot be discerned from the audio recording. While the recording from Paris’ Saint-Sulpice on November 16, 1969 is quite good (with the original French Swingle Singers providing the choir parts) it is an incomplete performance, with critical parts missing. The video made at Stockholm’s Gustav Vasa Church on November 6, 1969 is complete, in color, and can be viewed in its entirety on the website of the Duke Ellington Society of Sweden. (Part 1, Part 2). The Stockholm performance finds the Ellington band in top form, playing Ellington’s score with precision and energy. The Swedish Radio Choir, led by the legendary conductor Eric Ericson performs their parts with little effort (around this time, they recorded exceedingly difficult choral works such as Thomas Tallis’ 40-part motet, “Spem in Alium” and Richard Strauss’ “Deutsche Motette”). Alice Babs is the featured vocalist, with a beaming countenance to match her remarkable virtuosity. Even the young boy who reads “The Apple” is relaxed and confident. However, the most illuminating portions of the video appear in the final 25 minutes. Toney Watkins’ feature on “Don’t Get Down on Your Knees” is taken at a more robust tempo, and it takes place within the congregation. Of course, it is typical for a preacher to take the microphone and walk down the center aisle during a sermon, but in this case, it is Ellington’s way of breaking the fourth wall. By removing the invisible barrier between the performers and the audience, we are set up for the explosive finale.

After Babs’ initial rubato verses on “Praise God and Dance”, the tempo picks up and two black dancers in brightly colored African robes suddenly emerge from behind the altar. They move into the congregation while Watkins, Babs and Ellington demonstrate a hand-clapping pattern for the audience. While this is going on, the choir chants “Dance! Dance! Dance!” alongside a string of instrumental solos. All of this kinetic and musical energy raises the intensity of the music, and creates a visceral experience that is quite exciting on television, and must have been thrilling to witness in person. Fifty years after these concerts, there are many surviving audience members who specifically remember the hand-clapping and dancing in the aisles.

In 1973, Ellington received another reminder of his mortality when he was diagnosed with cancer in both lungs. Ellington did not share this news in public, but on October 24, when he premiered his Third Sacred Concert at Westminster Abbey, his health was failing him. The preparations for the concert were exhausting and troublesome. The band had rehearsed some of the music after hours at the Chicago nightclub, Mr. Kelly’s, while the John Alldis Choir rehearsed in London with Ellington’s choral director, Roscoe Ellis. However, Ellington continued to tinker with the music right up until the performance. Reportedly, Ellington had stayed up over 48 hours straight editing and re-writing music—a difficult task for anyone, but especially for a 74-year-old man with a fatal disease. Ellington and the band took the red-eye to London, landing there the day before the concert. They went right into rehearsal. Ellington complained about the legions of photographers which obstructed his work (eventually, he told them, “I can sit here and do this [pose for pictures and do interviews] or I can do a concert”). Paul Gonsalves had an epileptic seizure on the day of the concert and was taken to the hospital. Ellington was forced to give Gonsalves’ solos to Harold Ashby, and brought in another tenor saxophonist, Percy Marion, to play Gonsalves’ written parts. Meanwhile, Alice Babs had flown in from Sweden, and she learned her songs just hours before taking the stage. Shortly before the concert, Mercer Ellington went backstage to check on his father: He was lying on the cot, barely breathing, looking like a very tired, exhausted old man. From the way he was breathing, I began to get worried. However, at that moment, someone came to the dressing room to announce the arrival of Princess Margaret. Ellington sprung to his feet, put on his tails, and escorted the Princess to her seat. He would manage another magical rejuvenation the very next day.

Although the official subtitle of the Third Concert was “The Majesty of God”, Ellington told the audience at the outset that the true message of the concert was love. After a solo piano rendition of “The Lord’s Prayer”, Ellington segued into “My Love”, a feature for Alice Babs where the word “love” is reiterated 17 times in the first chorus. The melody is based on a simple two-note motive which moves in predictable ways to various pitch levels. Babs’ voice is noticeably darker here than on the Second Concert, and her diction is a little fuzzy, which makes it hard to understand all of the words. Harry Carney takes his usual spot in the opening number of the sacred concerts, reprising the melody with his still-strong baritone sax. “Is God a Three-Letter Word for Love?” is presented in two parts. Babs floats the lovely melody while communicating the lyric’s observations about God’s presence in nature and in love. When Babs sings the tune again, she is backed with sustained chords by the choir. The choir continues into the second part, where Toney Watkins delivers a rather pompous narration which elaborates on the song’s lyrics. Ellington improvises a solo piano interlude and then provides the sole accompaniment for Babs as she returns for the final chorus. The choir and trombones supply the quiet final chord.

“The Brotherhood” is dedicated to the United Nations, who sponsored this concert. The lyrics say little beyond “the United Nations brotherhood”, and except for Ashby’s tenor solo, the piece is completely forgettable. The choir feature, “Hallelujah”, isn’t much better. Lyrically, the song never goes beyond the title word, and despite a swinging background from Ellington, bassist Joe Benjamin and drummer Quenten “Rocky” White, the piece never takes flight. Ellington created a setting of his original phrase “Every Man Prays in His Own Language” for this concert. The recording starts with a fade-up on the unaccompanied choir, who are in the midst of the title phrase. Ashby returns, eventually leading the band in a melody statement and variation. The brass makes their first major appearance with another variation, but Carney is soon back to guide us into the choir’s a cappella setting of “The Lord’s Prayer”. A subdued instrumental passage—with Carney playing lead—introduces an “Amen” from the choir, and Babs’ solo version of “The Lord’s Prayer”, sung in her native Swedish. Then, in the most memorable part of the concert, trombonist Art Baron takes up the recorder for an unaccompanied solo. Babs and the choir then perform a wordless and tranquil piece which could stand by itself as a concert piece. Ellington narrates a short passage with subdued backing from the choir. Next, Watkins returns for another sermon, but the song “Ain’t Nobody Nowhere Nothin’ Without God” retreads the spoken passage from “In the Beginning, God”, and it fails to raise the roof like the Stockholm performance of “Don’t Get Down on Your Knees to Pray”. The medium tempo finale, “The Majesty of God” starts with a swinging Ellington solo, moves into a saxophone section melody, and includes a brief clarinet solo (likely Procope) before Ellington changes the tempo and leads into a duet between himself and Carney. After a short interlude, Babs performs Ellington’s dramatic setting of the text, The beauty of God is indescribable/The power of God is unappraisable/The sight of God is unimaginable/and one should know that the light of God is truth/and does not a shadow throw. The choir hesitantly enters with a reiteration of the main melody, with Babs improvising fills above. There is a brief waltz-time variation before a somewhat sudden and overblown ending.

After the concert, there were the usual groups of well-wishers to greet Ellington and the band. Ellington was as gracious as his health would allow, but eventually left for 10 Downing Street, where he was expected for a dinner party given by the Prime Minister in honor of the maestro. Ellington stayed there only 15 minutes, never took off his coat, and left, pleading exhaustion. The next day, the band traveled to Malmo, Sweden for a concert. Alice Babs was in the audience, and Ellington—now unexpectedly lively—invited Babs to the stage. Instead of the usual one-tune guest appearance, Babs was encouraged by Ellington to sing seven numbers with the band! One of the pieces was “Somebody Cares” a song written for the Third Concert, and performed the night before, but curiously left off the official recording. Ellington’s vocalists Toney Watkins and Anita Moore came onstage to provide the backup parts which were supposedly sung by the choir at Westminster. The concert was recorded by Swedish Radio, and is now available on the CD “Duke Ellington in Sweden, 1973”.

Just a few days later, Babs received a frantic call from Ellington. “Alice, you gotta save me!” said the familiar voice. A group of Spanish promoters had booked Ellington to perform the new sacred concert in Barcelona’s Santa Maria del Mar Basilica on November 10. The promoters had mistakenly assumed that Ellington was touring with both a choir and his band. Ellington did not have a touring choir and requested a local choir that had performed the Second Sacred Concert in Barcelona back in 1969. Unfortunately, they were not available, and Ellington had to scramble to assemble a sacred concert without the necessary choral forces. Babs was told that she would perform her usual solo numbers, and that it would be greatly appreciated if she could learn and sing some of the choir parts with Moore and Watkins. Babs agreed to help, but she was understandably nervous about the situation. She flew to Barcelona, arriving just hours before the concert. She fortified herself with a touch of whiskey, and made her way to the church, where Ellington had promised a 9:00pm rehearsal ahead of the 10:30pm concert. Ellington and the band failed to show up until 10:15, leaving Babs to rely on her sight-reading skills to get through the concert. And as fate would have it, the entire concert was filmed for nationwide TV.

Ellington’s program leaned heavily on his newly-composed music, but also included several items from the earlier sacred concerts. Ironically, he opens with the instrumental backing for “Somebody Cares”! Gonsalves, back from his illness, performs a tender solo over the gently flowing background. After a noticeably thinner Ellington enters, he conducts the band in the Second Concert’s theme, “Praise God”. Ellington moves to the piano for a unique rhythm section version of “Hallelujah”, with a featured spot for Joe Benjamin’s bass, alongside Quenten White’s snappy rimshots. It is something of a surprise when Ellington brings up Toney Watkins to sing “Heaven”. Watkins looks a little nervous about singing a piece so closely associated with Babs. He passes where she is sitting on stage and says something to her; Babs smiles in return, and Watkins rolls his eyes and starts to sing. To his credit, he sings it well, even if a little too dramatically. Johnny Hodges had passed away three years earlier, so the instrumental chorus is shared by Ellington (playing the melody in octaves) and Gonsalves (weaving variations). Watkins returns for the beguine section, which is played with a little more aggression than in Babs’ versions. “Supreme Being” makes a return appearance, with Roscoe Gill reading all of the spoken parts (with the band chanting the “good” responses). Considering the likelihood that the audience was not fluent in English, I wonder how many of them could actually follow this section. “The Majesty of God” takes several different turns in Barcelona. The opening chorus has been rescored for full band, Babs has an extra chorus of variations, and Gill returns for a spoken section (in time) with Babs’ improvised fills. On “Is God a Three-Letter Word for Love?” Toney Watkins’ sermon—spoken with much less dramaticism—is moved to the opening and is followed by Babs’ angelic rendition of the melody. Procope plays a full-chorus solo in the chalumeau register of his clarinet. Babs beams in reaction to Procope’s solo, and closes the piece in a heartfelt duet with Ellington.

“My Love” is presented without “The Lord’s Prayer” piano prelude. Babs’ diction is better here than at Westminster, so that the lyric’s themes of heavenly and Earthly love are easier to decipher. Carney’s solo is as rich as before (how he could sing through that horn!) and Babs’ closing chorus includes a few surprising—and glorious—leaps into the high register. There is a rather sudden cut to “The Shepherd”, here featuring Johnny Coles playing Cootie Williams’ old feature. Coles doesn’t growl as much as Williams, but he makes the piece his own with his unique approach to the material. “Tell Me It’s the Truth” is revived from the first concert, with Anita Moore giving the song the energy that Esther Marrow could not deliver. Toney Watkins improvises responses to Moore’s lead in this abbreviated arrangement. “Somebody Cares” finally appears as a trio for the vocalists. Moore takes the lead in the first chorus, with Babs singing fills above. A spirited scat duet between the women follows, and Watkins leads the trio in the out-choruses. As a song, “Somebody Cares” is a mere trifle, but the joy transmitted between the vocalists makes this performance a true delight. “Every Man Prays in His Own Language” opens with a new slow passage for the entire band. Apparently, it was so new that Ellington conducted it from a short score handed to him by Mercer! Ellington follows with an extended piano interlude. He then points to Quenten White, who sets a medium-up tempo, launching the melody and variation which opened the Westminster version. Then we cut to Babs’ Swedish rendition of “The Lord’s Prayer”. Ellington’s narration follows, with Art Baron’s recorder solo closing out this unique version of the arrangement.

The video of “Ain’t Nobody Nowhere…” reveals why Toney Watkins’ performance seems so grounded: he is obviously still learning the song, as he is seen holding a typed lyric sheet, and he keeps a finger on the page to guide him through the lyrics. Had Watkins sung this piece more often, he might have turned it into the show-stopper that “Don’t Get Down on Your Knees” had become. Unfortunately, he only had one more opportunity to perform it. To close the concert, Ellington goes back to the second concert’s finale, “Praise God and Dance”. After Babs’ sings her extended melody statement, there is a break for applause, and then Ellington kicks off the fast tempo. There are no guest dancers, so Moore, Watkins, Gill and Ellington all go into the audience, with Babs leading the hand-clapping from the stage. Gill and Watkins break loose with a few dance moves, and the vocalists (including Gill) do an impromptu four-part version of the theme over the band. Most of the solos from the earlier versions are gone, but Gonsalves plays a brief spot, and Harold “Geezer” Minerve makes up for the missing Cat Anderson by playing the final solo on piccolo! Then, as was true for all of the Sacred Concerts, Toney Watkins closes the program with an unaccompanied (and unamplified) rendition of “The Preacher’s Song” (aka “The Lord’s Prayer”).

After the Barcelona concert, Ellington would only perform one more sacred concert. It occurred on December 23, 1973 at the St. Augustine Presbyterian Church in Harlem. No information or recording has survived from this performance. However, we do know that Alice Babs did not perform at this concert. Ellington’s health worsened after returning to the US, and several (non-sacred) concerts in early 1974 were cancelled. His final appearance with the band took place in Sturgis, Michigan on March 22. Ellington was admitted to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York on March 25, and he would spend the final two months of his life there. He continued to work on his music, but he finally succumbed to cancer on May 24, 1974. Many of Ellington’s current and former sidemen died within months of him: Joe Benjamin on January 26, Paul Gonsalves on May 14, Tyree Glenn on May 18 and Harry Carney on October 8. Alice Babs continued performing for several years, and included many of her features from the sacred concerts in her solo repertoire. She took part in a memorial concert at the Swedish Royal Academy of Music (of which Ellington had been an honorary member since his initial visit to the country in 1939) and then recorded a superb tribute LP, “Serenading Duke Ellington”. On her LP with pipe organist Ulf Wessléin ,“What a Joy!” the entire second side is comprised of Ellington sacred music. The album also includes an improvised salute to Ellington, “God’s Messenger Boy”. [Note that the CD reissues titled “What a Joy” do not include these tracks. The original LP is the only source at present.]

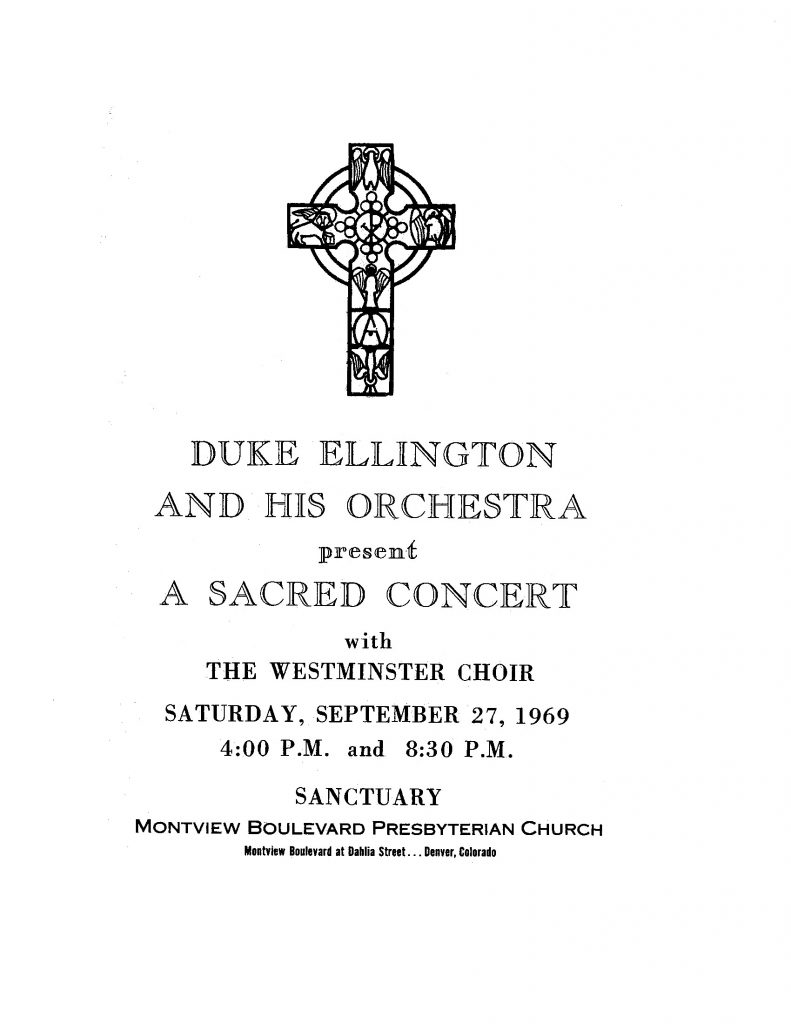

Ellington’s Sacred Concerts may not have inspired sweeping social changes, but it certainly made small inroads. Montview Presbyterian Church is located in the Park Hill neighborhood of Denver. For many years, Park Hill was a white upper-middle class area. The Denver Public Library has a pamphlet dated from 1932 which attempts to scare the residents by stating that blacks had infiltrated the area. Following World War II, there was a concerted effort by upscale blacks to move from the lower-income Five Points neighborhood to Park Hill. However, the combined efforts of bankers who would not grant mortgages to blacks in Park Hill and realtors who discouraged blacks from exploring homes in that area, kept Park Hill as an essentially whites-only neighborhood. But the progressives who lived in Park Hill had no issues with blacks moving into the area, as long as they kept up their homes and lawns. In 1960, members of eight Park Hill churches met at Montview to form the Park Hill Action Committee which strove to integrate the neighborhood and eliminate racial discrimination in Denver. Montview’s minister, Dr. Arthur Miller spearheaded the efforts, and by the end of the 1960s, Montview hosted Martin Luther King to speak at the church. In 1967, Dr. Albert Fay Hill replaced Miller as minister—although Miller continued to be active at the church. It is believed that Hill knew Duke Ellington, or at least had a connection to his agent. When Ellington’s band was scheduled to perform the Second Sacred Concert on September 27, 1969, the church launched an energetic campaign to assemble an audience from across the Park Hill neighborhood and Denver as a whole. At the time, Montview had a primarily white congregation, but at the sold-out concerts, several surviving choir members said that there were many black people in the audience—more than they had ever seen at Montview before. The communion of Ellington’s sacred music brought this community together like few events before or after. Even for a non-traditional Christian like Duke Ellington, an accomplishment like that should earn him a few extra days in Heaven.

Thanks to Adam Waite, Barbara Lovelace-Williams, Jean Sibley, Phyllis Bryant, Marcia Whitcomb, Kathy Hoy-Gipe, Vicki Burrichter, Barbara Hulac, Orlando Archibeque, Mona Granager, Sarah Ganderup, Mara Miller, and Olive (Molly) Simpson. Special thanks to Ulf Lundin and the AMAZING Duke Ellington Society of Sweden for posting (and allowing me to embed) the rare videos of the Paris, Stockholm and Barcelona concerts.