On the surface, Johnny Mercer’s lyric to the song “P.S. I Love You” is nothing more than a letter from a wife to her traveling husband, listing the simple everyday activities of her life. But there is a deeper subtext to Mercer’s words: it is a song about marital fidelity where the wife’s list of mundane tasks is punctuated with the recurring title line. “P.S. I Love You” has been recorded by many great vocalists, including Billie Holiday and Frank Sinatra, but no singer captured the subtext of the song as well as Susannah McCorkle. In her 1988 recording of the song, McCorkle embodies the lyric as she takes on the role of  the lonely housewife. She sings the first line alone—“Dear, I thought I’d drop a line”—with a dramatic pause after the first word. After guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli joins in, McCorkle hews close to the melody and adjusts the rhythm to make it more conversational. There’s a teasing quality in her delivery of the crucial line I’m in bed at night at nine but with the appearance of the title line, it’s clear that she’s alone in that bed, and that her husband is the only person she wants by her side. Ken Peplowski is the only other musician on the track, and his clarinet solo (which also stays close to the melody) offers comfort and solace to McCorkle’s narrative.

the lonely housewife. She sings the first line alone—“Dear, I thought I’d drop a line”—with a dramatic pause after the first word. After guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli joins in, McCorkle hews close to the melody and adjusts the rhythm to make it more conversational. There’s a teasing quality in her delivery of the crucial line I’m in bed at night at nine but with the appearance of the title line, it’s clear that she’s alone in that bed, and that her husband is the only person she wants by her side. Ken Peplowski is the only other musician on the track, and his clarinet solo (which also stays close to the melody) offers comfort and solace to McCorkle’s narrative.

That recording, and the album on which it appeared, “No More Blues”, was my introduction to Susannah McCorkle and it made me a devoted fan. As I collected her albums, I discovered a young vocalist with a deep and abiding love for the Great American Songbook, who researched her material, and discovered rarely heard gems and obscure alternate lyrics. She was fluent in several languages, and wrote brilliant translations of songs originally written in French, Italian and Portuguese (the latter featured on her second Concord album, “Sabia”). She also spotlighted contemporary music that honored the Songbook tradition, including the brilliantly funny songs of Dave Frishberg. She was among the first vocalists to sing the heart wrenching Johnny Mandel/Alan & Marilyn Bergman opus “Where Do You Start”. That song seemed to touch McCorkle personally, and in my only opportunity to speak with her, she confirmed that she broke into tears while recording the song, and continued sobbing for several minutes after the recording was completed. I learned that she was a published author and had won awards for her short fiction. As a young jazz writer, I desperately wanted the challenge to write liner notes for one of her albums, and for years I lobbied for the opportunity. However, I did not have a newspaper or magazine job at the time, so the notes were written by others.

In the early morning hours of May 19, 2001, McCorkle committed suicide by jumping from the window of her 16th story Manhattan apartment. It wasn’t until the publication of Gwenda Blair’s 2002 article “JazzBird” and Linda Dahl’s 2006 biography, “Haunted Heart” that the world learned why McCorkle decided to end it all: she was bipolar and was not taking the medications she needed to maintain her equilibrium. Like many artists, she felt that she lost her creative edge when taking antidepressants, and she experimented with homeopathic methods. She had faced several professional setbacks in the months prior to her death, including cancellations of her recording contract and her yearly engagement at the Algonquin’s Oak Room. She had been married and divorced three times, experienced sexual abuse as a child, and fought breast cancer as a woman. But the demons in her soul became more than she could handle, and while keeping up her confident public image, she updated her will, wrote a detailed suicide note, and ended her life.

To be fair, McCorkle brought on some of her own problems. She was, in her own words, “a hopeless romantic” and Dahl’s book offers several examples of McCorkle being unable to reconcile real-life relationships with her elaborate fantasies. Similarly, she seemed to embrace the ideas of being a writer and a jazz singer, but had little interest in undergoing the training necessary to excel in the field. Dahl reports that McCorkle rarely pulled A’s in her English classes at Berkeley, but found early success writing satiric pieces for a school newspaper. After hearing recordings of Billie Holiday, McCorkle was determined to become a jazz singer, but she never had any formal music training. In a jaw-dropping quote from Dahl’s book, McCorkle said If you just let go and make people feel a song, nobody’s going to worry about whether you read music or breathe right. McCorkle never learned either skill. Any vocal coach would have told her that breath control is the single most important element of singing. Put simply, without proper support of air, the vocal cords are needlessly stressed and will eventually fail. By not reading music or knowing any music theory, McCorkle was sometimes at a loss in explaining what she wanted her musicians to play behind her. And as McCorkle had a reputation as a notorious perfectionist, her inability to communicate in technical musical terms made things frustrating for both her and her musicians (Dahl quotes several musicians who vowed to never work with McCorkle again after spending a few hours with her on a recording session or a gig. However, McCorkle’s last pianist, Allen Farnham told me that her last trio was very comfortable in interpreting McCorkle’s requests). The quote also reveals another troubling aspect: that McCorkle’s primary interest was in pleasing an audience rather than taking care of her instrument.

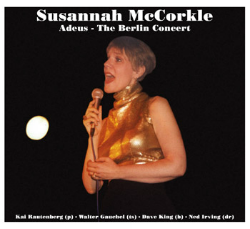

McCorkle could certainly please an audience, as a newly released CD “Adeus: The Berlin Concert” (Sonorama C-86) makes clear. Recorded in 1996 at the 60th birthday party of German radio host Siegfried Schmidt-Joos, McCorkle performs an hour-long set for a very enthusiastic audience (Dahl actually  mentions this performance in her book, but conflates it with a disastrous big band gig that occurred later in the year). While McCorkle has occasional issues with intonation, hoarseness and other vocal problems, she’s in generally fine form, creating a superb melodic variation on “Zing Went the Strings of My Heart”, singing a cappella on the opening lines of Paul Simon’s “Still Crazy After All These Years” and matching the band’s rhythmic feel on “Adeus America”. She sings a surprising interval on the final chorus of “Get Out of Town”, gently admonishes the audience to keep quiet before commencing her spellbinding version of Holiday’s “That Ole Devil Called Love”, and relates “Don’t Fence Me In” to her personal relationships. Although she has pitch issues throughout “I Thought About You”, her luxurious approach to the rhythm is fascinating. McCorkle always said she preferred to sing ballads, but she had a strong feeling for rhythm songs, and her exuberant performance of Louis Armstrong’s “Swing That Music” is one of the set’s highlights. Her melancholy take on “That Old Feeling” leads to a burning “You Do Something to Me” which uses the rarely-heard verse as a bridge to the final chorus. She sings her own English translation on Ary Barroso’s tender “Pra Machucar Meu Coração” and sounds quite happy grooving through “S’Wonderful” and “Bye Bye, Baby”. The quartet of local musicians is rather rough-hewn, but McCorkle seems pleased with their performance.

mentions this performance in her book, but conflates it with a disastrous big band gig that occurred later in the year). While McCorkle has occasional issues with intonation, hoarseness and other vocal problems, she’s in generally fine form, creating a superb melodic variation on “Zing Went the Strings of My Heart”, singing a cappella on the opening lines of Paul Simon’s “Still Crazy After All These Years” and matching the band’s rhythmic feel on “Adeus America”. She sings a surprising interval on the final chorus of “Get Out of Town”, gently admonishes the audience to keep quiet before commencing her spellbinding version of Holiday’s “That Ole Devil Called Love”, and relates “Don’t Fence Me In” to her personal relationships. Although she has pitch issues throughout “I Thought About You”, her luxurious approach to the rhythm is fascinating. McCorkle always said she preferred to sing ballads, but she had a strong feeling for rhythm songs, and her exuberant performance of Louis Armstrong’s “Swing That Music” is one of the set’s highlights. Her melancholy take on “That Old Feeling” leads to a burning “You Do Something to Me” which uses the rarely-heard verse as a bridge to the final chorus. She sings her own English translation on Ary Barroso’s tender “Pra Machucar Meu Coração” and sounds quite happy grooving through “S’Wonderful” and “Bye Bye, Baby”. The quartet of local musicians is rather rough-hewn, but McCorkle seems pleased with their performance.

It was just a little over five years later when Susannah McCorkle jumped to her death. But what if she hadn’t jumped? Her fortunes could have turned around with a new recording contract, and in retrospect, it was probably best that she wasn’t performing at the Algonquin through September 2001. McCorkle’s unique straddling of jazz and cabaret might have found a new audience as a new wave of jazz singers emerged. However, there is one crucial difference between McCorkle and the younger vocalists: virtually all of the younger singers have thorough musical training and are able to read music, sing with proper technique, and write their own arrangements. Earlier generations of singers might have been able to get away without musical training, but if McCorkle was to survive, she would have had to adapt to the changing times. Still, there is a void where McCorkle once stood. With the exception of Stacey Kent, few contemporary singers tell stories with the same intensity as McCorkle, and the number of singers who research with the same thoroughness as McCorkle is smaller still. Perhaps the new live disc will fall into the hands of a gifted singer who will pick up the torch that McCorkle left burning some 14 years ago.