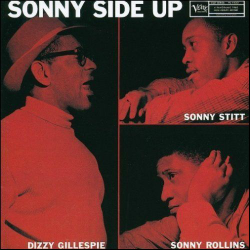

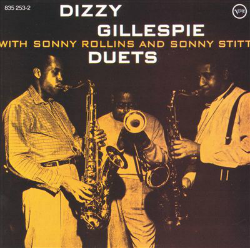

Norman Granz loved contrasts. Time and again, he would assemble diverse groups of musicians in the recording studio and then let the sparks fly. It was a very successful formula for creating exciting jazz, even when the musicians avoided the battle-like atmosphere that Granz wanted. But when the conditions were right, even the battles could be both musical and thrilling. Dizzy Gillespie joined the Granz roster in 1953, and he was the catalyst for many summit meetings, including superb albums with Stan Getz, Roy Eldridge and Oscar Peterson. However, there is little doubt that the greatest of these recordings were the two 1957 albums with Sonny Rollins and Sonny Stitt, issued as “Sonny Side Up” and “Duets”.

The pairing of Rollins and Stitt was highly inspired. More important than their common nicknames (and the punning album title), tenor saxophonists Rollins and Stitt were both influenced by Charlie Parker, but each took a vastly different approach to improvisation. Stitt transferred Parker’s white-hot intensity to the tenor after several fans and critics pointed out the tonal similarity of their alto sounds. Rollins was a more thoughtful player who expanded the vocabulary of bop improvisation by incorporating thematic elements into his solos and by experimenting with different melodic shapes and unusual phrase lengths. Stitt enjoyed the competitive nature of the jam session, but Rollins stayed away from cutting contests (there was the famous tenor battle with Rollins and John Coltrane on “Tenor Madness” but I’ve never sensed any real chemistry between the two giants on this recording). In 1957, Rollins was the hottest young tenor player around and he was free-lancing, recording brilliant albums for a wide range of independent record labels. Granz undoubtedly wanted Rollins on his roster, and an album with Gillespie was probably the best way to bring him on board. Stitt had worked with Gillespie on several recordings going back to 1946, and the trumpeter may have suggested the dual tenor setup. Gillespie definitely supplied pianist Ray Bryant and drummer Charli Persip (both were playing with Gillespie’s band at the time) and when asked about a suitable bassist, Bryant recommended his brother Tommy.

The pairing of Rollins and Stitt was highly inspired. More important than their common nicknames (and the punning album title), tenor saxophonists Rollins and Stitt were both influenced by Charlie Parker, but each took a vastly different approach to improvisation. Stitt transferred Parker’s white-hot intensity to the tenor after several fans and critics pointed out the tonal similarity of their alto sounds. Rollins was a more thoughtful player who expanded the vocabulary of bop improvisation by incorporating thematic elements into his solos and by experimenting with different melodic shapes and unusual phrase lengths. Stitt enjoyed the competitive nature of the jam session, but Rollins stayed away from cutting contests (there was the famous tenor battle with Rollins and John Coltrane on “Tenor Madness” but I’ve never sensed any real chemistry between the two giants on this recording). In 1957, Rollins was the hottest young tenor player around and he was free-lancing, recording brilliant albums for a wide range of independent record labels. Granz undoubtedly wanted Rollins on his roster, and an album with Gillespie was probably the best way to bring him on board. Stitt had worked with Gillespie on several recordings going back to 1946, and the trumpeter may have suggested the dual tenor setup. Gillespie definitely supplied pianist Ray Bryant and drummer Charli Persip (both were playing with Gillespie’s band at the time) and when asked about a suitable bassist, Bryant recommended his brother Tommy.

To test the waters, Granz scheduled a double session on December 11, 1957. Gillespie and the rhythm section were there throughout, but the tenors were  brought in separately. Two extended tracks by each pairing were issued on the album “Duets”, but the CD reissue includes an additional two tracks featuring the group with Stitt. The tracks run about 10 minutes each, giving the soloists plenty of time to stretch out. Both of the tracks with Rollins are blues, “Wheatleigh Hall” and “Sumphin’”. “Wheatleigh” burns from the start, with Rollins getting right to work developing Gillespie’s original theme. Rollins had plenty of experience with lightning-fast tempos from his days with the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet, and he had a unique way of breaking up his phrases so that his thought process never sounded rushed. In contrast, Gillespie starts with long strings of notes played on top of the beat, and then breaks up the phrases as the solo progresses. “Sumphin’” is a slinky medium-tempo line with a secondary melody played against Bryant’s piano. Rollins is again highly thematic in his solo (as Gunther Schuller pointed out, Rollins was fond of creating thematic improvisations on blues changes). Gillespie’s solo is a delight, with great vocalized effects mixed in with the bop licks.

brought in separately. Two extended tracks by each pairing were issued on the album “Duets”, but the CD reissue includes an additional two tracks featuring the group with Stitt. The tracks run about 10 minutes each, giving the soloists plenty of time to stretch out. Both of the tracks with Rollins are blues, “Wheatleigh Hall” and “Sumphin’”. “Wheatleigh” burns from the start, with Rollins getting right to work developing Gillespie’s original theme. Rollins had plenty of experience with lightning-fast tempos from his days with the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet, and he had a unique way of breaking up his phrases so that his thought process never sounded rushed. In contrast, Gillespie starts with long strings of notes played on top of the beat, and then breaks up the phrases as the solo progresses. “Sumphin’” is a slinky medium-tempo line with a secondary melody played against Bryant’s piano. Rollins is again highly thematic in his solo (as Gunther Schuller pointed out, Rollins was fond of creating thematic improvisations on blues changes). Gillespie’s solo is a delight, with great vocalized effects mixed in with the bop licks.

When Stitt replaced Rollins for the second half of the session, the group started with the only non-blues of the day, Gillespie’s Latin-flavored “Con Alma”. This was the song’s first small-group recording, and the CD includes two takes. On the alternate, Stitt jumps right into the changes with an aggressive on-the-beat approach. After hearing Rollins for the previous 20 minutes, this style comes as a shock, and it makes less of a contrast with Gillespie’s style. But on the master take, Stitt relaxes into the groove and creates a much more varied rhythmic palette. Gillespie also seems more poised and relaxed on the master take, spinning out incredibly complex melodic lines with surprising rhythmic accents along the way. The rhythmic feel is also improved on the master take, with Persip keeping the eighth-note pulse on maracas throughout (on the alternate, he switches between hand drum and set, creating abrupt changes in the background). The other unreleased take, “Anythin’” features Stitt’s only work on alto for the date. And while Stitt certainly sounds like Bird on this track, his sound here is less intense than Parker’s, and that was probably a conscious decision by Stitt. When Gillespie takes over, Persip sets up a great backbeat and the trumpeter digs in for several soulful choruses. Then Stitt returns on tenor, bringing back the aggressive phrasing from the alternate of “Con Alma”. The final track, “Haute Mon’” rolls along in 12/8 time, with Persip adding to the atmosphere with finely shaded cymbals. There’s quite a bit of collective improvisation throughout this performance and that makes the piece stand out from the other tunes, which were straight-ahead blowing vehicles. Overall, the solos are shorter and the inclusion of bass and drum solos along with the collective playing makes this an intriguing close for the “Duets” album.

The follow-up session was scheduled eight days later, on December 19, 1957. This time, both tenors would be present together along with Gillespie and the rhythm section. A persistent piece of historical trivia has it that Gillespie called both Rollins and Stitt in the week between the sessions, telling each that the other tenor man was out to cut him. Whether or not that really happened, the sparks certainly flew at the recording session. It seems like the entire band picked up the momentum right where they left off the previous week. In fact, the first track they recorded that day was the track everyone wanted to hear: the tenor sax battle between Rollins and Stitt on “The Eternal Triangle”. This ultra-fast “I Got Rhythm” contrafact was written by Stitt, and while others have recorded the piece, none have ever come close to this version. After a very clean exposition of the melody, Rollins jumps in with a meaty solo, nearly matching Stitt’s aggressive style from the previous week. His ideas seem to flow without cessation, and even a squeaky reed fails to deter him. Only a change of timbre marks the switch-off between Rollins and Stitt, and if anything, the intensity continues to build as Stitt plays. Then Rollins and Stitt trade fours and it’s clear that each of them was ready to match the other, phrase by phrase. Gillespie was certainly inspired by all of the revelry, and his solo is electric, with brilliant forays into the high register and exciting execution. Ray Bryant keeps the rhythmic intensity going with an incisive solo before Gillespie comes back for a round of fours with Persip. (This sequence may have gone on a bit longer at the session, for there is an audible splice before the recapitulation on the original LP).

The rest of “Sunny Side Up” doesn’t reach the ecstatic heights of “Eternal Triangle”, but it is all superbly performed. “On the Sunny Side of the Street” must have seemed a natural for this record, and Gillespie’s arrangement and vocal offer delightful variations on the original melody. Now that the combat is over, Stitt and Rollins revert back to their recognizable—and considerably different—styles (Somehow, the solo order was reversed in the original liner notes). Avery Parrish’s “After Hours” turns the spotlight to Ray Bryant and the laid-back 12/8 groove allows everyone to relax. Bryant retains many of the riffs from the original Erskine Hawkins version, including the recurring tag at the end of each chorus. A muted Gillespie serves up the grits n’ gravy followed by Rollins with his rough-hewn sound (on other recordings from this period, Rollins played with a much smoother tone, leading me to suspect that he was experimenting with different mouthpieces and reeds). Stitt is in excellent form here, with an intense, piercing tone and a perfectly modulated approach to the rhythm. The final track recorded was “I Know That You Know”, which had been the basis of a classic 1928 recording by clarinetist Jimmie Noone. Rollins loved to resurrect old pop songs, and he probably brought this song to the session. Rollins plays a marvelous stop-time solo on this track, which clearly highlights his rhythmic acuity and foretells the brilliant unaccompanied solos that would become a regular part of his repertoire.

Both “Duets” and “Sonny Side Up” were originally issued in mono, but in the CD era, reissue producer Phil Schaap tried to reconstruct the albums in stereo. The “Duets” session reels were recorded in stereo, but the sound was out of phase, so once that problem was corrected, the album sounded fine in stereo. However, some of the stereo reels for “Sonny Side Up” must have been lost or damaged, because the sound jumps back and forth from mono to stereo throughout the Verve Master Edition CD. Short of going back to the original mono LP, there’s no other way to hear this classic album without these jarring audio manipulations.

However, the best postscript to these recordings may come from the following video clip. Recorded at a 1987 tribute to Gillespie, it is a reunion with Rollins, and they play the first track they recorded together, “Wheatleigh Hall”. The individual sounds of the two men had changed with the years—Gillespie’s weakened by age and health, and Rollins’ toughened through an r&b-influenced style—but their gifts as improvisers remained unmatched. Rollins opens his solo with another wonderful stop-time episode before soaring above the cooking rhythm section. Gillespie is fearless, with ideas that rival those of his halcyon days. This performance shows that Gillespie and Rollins were easily able to recapture the excitement that had originally created 30 years before.