Playlist

Dan Morgenstern has written that reading a discography can be as compelling as a good mystery novel. Certainly, the raw information contained in discographies can lead our inner detectives to discover recordings and learn more about the origin and development of artists. However, the same technique can also be used to research a song. In the case of “Body & Soul”, the discographies open up a maze of riddles and offer unique insights on the history of one of the great popular standards. Most Tin Pan Alley songs were premiered in Broadway shows or revues, but by the time Libby Holman sang “Body & Soul” for its first Broadway audiences on October 15, 1930, the song had been recorded 22 times and had already become a hit in England. Those recordings offer us the opportunity to hear “Body & Soul” before it became sacrosanct, when arrangers and performers felt free to create audacious approaches to the original material.

The song’s composer, Johnny Green was not a jazz musician, but he understood jazz and he included several features in “Body & Soul” which would appeal to jazz musicians through the years. “Body & Soul” is famously known as “the song that begins with a rest”. The opening motive—which is repeated several times in the song—starts with a silent downbeat and a sixteenth-note pickup to the second beat. This simple but engaging syncopation propels the melody. The same idea is transformed in the bridge to a repeated eighth/dotted quarter note pattern. Each of the three A sections builds to the felicitous triplet pattern to which the title phrase is set. The entire song is set over a harmonic sequence that was quite daring for its time. It opens not with the tonic chord, but the minor chord on the supertonic (ii). The elaborate chord structure for the bridge was Green’s elegant solution of moving from the home key of D-flat, through the unrelated keys of D major and C major and back again to the E-flat minor chord that opens the final strain. Apparently, the bridge was originally discarded from an earlier Green song, “Coquette”, but inserting the bridge of “Body & Soul” into “Coquette” creates a composite that sounds awkward, to say the least!

In the summer of 1929, Green and his lyricists, Edward Heyman and Robert Sour, wrote four songs for singer Gert rude Lawrence. “Body and Soul” was the torch song, and the only one remembered today. (According to Sour, the fourth credited songwriter on “Body and Soul”, Frank Eyton, “didn’t change a comma” of the lyrics; Will Friedwald states that Eyton influenced British bands to play the song). While Lawrence included the song in her act and even invested a small amount towards its publication, she never recorded “Body & Soul”—even after it became a hit. The song caught the attention of British bandleader Bert Ambrose when he heard Lawrence perform it on the radio. Ambrose was so taken by the song that he commissioned an arrangement so that his band could play it the following night! However, it was Ambrose’s chief rival, Jack Hylton, whose band made the first recording of “Body & Soul” on February 7, 1930. Ambrose followed with his own recording on February 22. Not to be outdone, Hylton went back into the studio on February 25 to record an entirely new 4 ½ minute “concert” arrangement! (If the reader wonders just how these two bandleaders kept such close tabs on each other, the answer may have been with saxophonist Joe Crossman, who discographies say might have appeared on all three recordings—a classic double agent!)

rude Lawrence. “Body and Soul” was the torch song, and the only one remembered today. (According to Sour, the fourth credited songwriter on “Body and Soul”, Frank Eyton, “didn’t change a comma” of the lyrics; Will Friedwald states that Eyton influenced British bands to play the song). While Lawrence included the song in her act and even invested a small amount towards its publication, she never recorded “Body & Soul”—even after it became a hit. The song caught the attention of British bandleader Bert Ambrose when he heard Lawrence perform it on the radio. Ambrose was so taken by the song that he commissioned an arrangement so that his band could play it the following night! However, it was Ambrose’s chief rival, Jack Hylton, whose band made the first recording of “Body & Soul” on February 7, 1930. Ambrose followed with his own recording on February 22. Not to be outdone, Hylton went back into the studio on February 25 to record an entirely new 4 ½ minute “concert” arrangement! (If the reader wonders just how these two bandleaders kept such close tabs on each other, the answer may have been with saxophonist Joe Crossman, who discographies say might have appeared on all three recordings—a classic double agent!)

The Ambrose and Hylton recordings owe a lot to Paul Whiteman, from the elaborate arrangements with strings to the strained tones of vocalists Sam Browne (Ambrose) and J. Pat O’Malley (both Hylton sides), as well as the rhythm, which bounces more than swings. Yet they all have interesting moments: there is a baritone sax solo (possibly Our Man Crossman) with violin accompaniment on the first Hylton version. At the bridge, the strings and sax reverse roles with the baritone playing a simple (and possibly improvised) countermelody. The Ambrose version opens with a lovely chalmeau clarinet introduction over a cloud of chords, followed by Browne’s vocal, accompanied with an elegant violin obbligato. And the Hylton concert recording includes a highly effective rat-a-tat trumpet soli within the verse. (Unfortunately, the fine verse to “Body & Soul”—which also changes keys at its halfway point— has been ignored over the years, but it appears in most of the recordings discussed here). It appears that Elsie Carlisle was the first to sing the verse on record, but the words she sings do not appear in any other version I’ve heard: You’re making me blue/All that you do seems unfair. You try not to hear/turn a deaf ear to my prayer. It seems you don’t want to see/what you are doing to me. My arms are longing to caress you/and to my heart they long to press you, sweetheart. While these lyrics are completely different than the version printed in the American sheet music, the rest of the words sung by O’Malley, Browne and Carlisle are very close to the version we all know. The exceptions are I wait and sigh (instead of For you I sigh) and the second half of the bridge: No use pretending/Don’t say it’s the ending! I wish I could have one more chance to prove dear (later restructured as Are you pretending? It looks like the ending, unless I could have one more chance to prove, dear). This version also included the words My life a hell you’re making, which usually became a wreck in view of censorship issues. For identification purposes, we’ll refer to these words as “the British lyrics”.

In the period between February and May of 1930, there were five other British recordings of “Body & Soul”. Pete Mandell’s version from May 5 is without merit, featuring a stiff vocal by Jack Plant, and a rhythm section drawn down by a drummer who loudly pounds out quarter notes on his tom-tom. Spike Hughes’ (below left) recording from March 12 is much more supple, thanks to the buoyant two-beat bass of the leader. Drummer Val Rosing takes the vocal. He does little harm to the song, and his drumming is subtle enough that it’s hard to discern just when he returns to his kit. Pianist Carroll Gibbons’ version is now believed to have been recorded on February 19 (but originally marked as late 1929, which would have made it the song’s debut recording). Gibbons’ recording holds up well today. It is a trio version with Gibbons’ piano and unidentified violin and clarinet. Gibbons sounds like an unusually gifted hotel pianist, but he takes liberties with the melody and adds a few effective tempo changes. The violinist seems fairly adept at light improvisation, and the clarinetist has a rich sound in the chalmeau register. (The other recordings, a February 15 version with Arthur Rosebery’s orchestra and a May 30 rendition by Gil Alfredo’s band—with Sam Browne again on vocal—were not available in print or online at press time).

violin and clarinet. Gibbons sounds like an unusually gifted hotel pianist, but he takes liberties with the melody and adds a few effective tempo changes. The violinist seems fairly adept at light improvisation, and the clarinetist has a rich sound in the chalmeau register. (The other recordings, a February 15 version with Arthur Rosebery’s orchestra and a May 30 rendition by Gil Alfredo’s band—with Sam Browne again on vocal—were not available in print or online at press time).

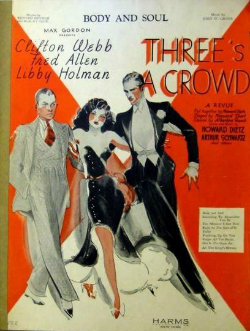

After Alfredo’s recording, there were no other versions of “Body & Soul” made until Paul Whiteman’s version of September 10. In the meantime, the song was incorporated into the Broadway revue, “Three’s A Crowd”. The show was produced by Max Gordon, later the proprietor of the Village Vanguard, and starred Fred Allen, Clifton Webb and Libby Holman (the supporting cast included another upcoming star, Fred MacMurray). Most of the music was by Howard Dietz and Arthur Schwartz, and for a while, it looked as though “Body & Soul” would be cut. Holman didn’t like the lyrics, the arrangement was problematic, and the staging involved moving Holman on an elaborate set of pulleys which rarely worked as designed. Ralph Rainger was hired to fix the arrangement, the pulleys were discarded, and the lyrics underwent several rewrites. Apparently, one of the early versions was given to a song plugger, for all of the “Body & Soul” recordings made in September (and most of those made in October) feature what we will call “the alternate lyrics”. These lyrics have been recorded several times in later years and include the couplets My days are sad and lonely/for I have lost my one and only, I was a mere sensation/My house of cards had no foundation and My life revolves about you/What earthly good am I without you? The verse was changed too, opening with I’m lost in the dark/Where is the spark for my love?, and later incorporating the dreadful rhymes of closed and supposed and even worse, abandoned and planned on. Thankfully, what didn’t change was Green’s melody and harmony.

Paul Whiteman (right) and Johnny Green were friends, and were probably introduced to each other through George Gershwin. Whiteman was  particularly fond of “Body & Soul”, both for the harmonic progression of the bridge and the modulation in the verse. He had his pianist Roy Bargy create an arrangement and the resulting recording became a major hit. The style is similar to the Ambrose and Hylton recordings, but Bargy’s setting is far superior, including a brilliant condensation of the melody in the introduction, a fine theme chorus for the orchestra (after Jack Fulton’s ridiculously high tenor vocal), an antiphonal flair in the verse, and a side-by-side comparison of Andy Secrest’s Bix-like cornet and Nat Natoli’s straight trumpet. Another orchestral version from September 17 issued by Fred Rich & His Orchestra also features contrasting soloists, this time the trombones of straight man Tommy Dorsey and growling jazzer Jack Lacey. And again, the weakest part of the side is the effeminate vocal performed by Dick Robertson.

particularly fond of “Body & Soul”, both for the harmonic progression of the bridge and the modulation in the verse. He had his pianist Roy Bargy create an arrangement and the resulting recording became a major hit. The style is similar to the Ambrose and Hylton recordings, but Bargy’s setting is far superior, including a brilliant condensation of the melody in the introduction, a fine theme chorus for the orchestra (after Jack Fulton’s ridiculously high tenor vocal), an antiphonal flair in the verse, and a side-by-side comparison of Andy Secrest’s Bix-like cornet and Nat Natoli’s straight trumpet. Another orchestral version from September 17 issued by Fred Rich & His Orchestra also features contrasting soloists, this time the trombones of straight man Tommy Dorsey and growling jazzer Jack Lacey. And again, the weakest part of the side is the effeminate vocal performed by Dick Robertson.

While male singers like Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett all had great success with “Body & Soul”, the song has belonged to female singers from the beginning. Three of the era’s top female singers recorded “Body & Soul” between September 12 and October 7, 1930. Helen Morgan was the first and she seems to drown in self-pity, despite a fine backing arrangement by Leonard Joy. Ruth Etting holds her composure through most of her September 29 recording,  but then pours on the bathos in the final eight bars. Annette Hanshaw (left) was a favorite vocalist amidst the white jazz New York musicians, and on her version, she sings the song simply, letting the lyrics tell the story. Hanshaw’s delivery was not as dramatic as Morgan’s or Etting’s, but her heartfelt reading of—as she sings it— My life revolves about him/Lord knows I’m just no good without him speaks volumes to the art of understatement.

but then pours on the bathos in the final eight bars. Annette Hanshaw (left) was a favorite vocalist amidst the white jazz New York musicians, and on her version, she sings the song simply, letting the lyrics tell the story. Hanshaw’s delivery was not as dramatic as Morgan’s or Etting’s, but her heartfelt reading of—as she sings it— My life revolves about him/Lord knows I’m just no good without him speaks volumes to the art of understatement.

With the Broadway opening of “Three’s A Crowd” set for October 15, there was a flurry of recordings between September 29 and October 10 of both “Body & Soul” and the show’s other perceived hit, “Something to Remember You By”. At least nine recordings were made during those two weeks, including one for Brunswick by the woman who officially introduced it, Libby Holman (below right). Holman’s recording is important, but not particularly for her straight-laced interpretation. Rather, it is because Holman’s recording is probably the first recording of the standard lyrics. Here again, the discographies provide a tempting riddle: the recording date is traditionally listed as October 1930 with no specific date attached. However, we do have matrix numbers for her versions of “Body & Soul” and “Something to Remember”, and the next tw o matrix numbers in the sequence are for Ozzie Nelson’s recording of the same two numbers (yes, that Ozzie Nelson). Nelson’s recording has also been traditionally listed as October 1930, but discographer Ross Laird has pinpointed the Nelson recording to October 8. Matrix numbers are not always a very accurate way to pinpoint recording dates—companies sometimes reserved numbers for special recordings, although it’s not clear why—but if we are to believe these particular numbers, Holman’s recordings were made between October 6 and 8, certainly in the same studio as Nelson, and possibly right before Nelson’s session! What makes this scenario particularly interesting is that Nelson sings the alternate lyrics, just like Hanshaw on October 7 and Louis Armstrong (in Los Angeles) on October 9. Apparently, none of the recording artists had been informed that the song’s lyrics had changed again, and that this time, the results would be published on the sheet music. There’s a chance that this little deception was done on purpose: Holman’s recording was released on October 13—approximately six days after the original recording and only two days before the Broadway premiere—and the final lyric might have been withheld from other artists to give Holman’s recording an extra boost.

o matrix numbers in the sequence are for Ozzie Nelson’s recording of the same two numbers (yes, that Ozzie Nelson). Nelson’s recording has also been traditionally listed as October 1930, but discographer Ross Laird has pinpointed the Nelson recording to October 8. Matrix numbers are not always a very accurate way to pinpoint recording dates—companies sometimes reserved numbers for special recordings, although it’s not clear why—but if we are to believe these particular numbers, Holman’s recordings were made between October 6 and 8, certainly in the same studio as Nelson, and possibly right before Nelson’s session! What makes this scenario particularly interesting is that Nelson sings the alternate lyrics, just like Hanshaw on October 7 and Louis Armstrong (in Los Angeles) on October 9. Apparently, none of the recording artists had been informed that the song’s lyrics had changed again, and that this time, the results would be published on the sheet music. There’s a chance that this little deception was done on purpose: Holman’s recording was released on October 13—approximately six days after the original recording and only two days before the Broadway premiere—and the final lyric might have been withheld from other artists to give Holman’s recording an extra boost.

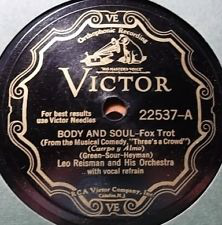

One New York bandleader did know that the lyrics had been revised. Leo Reisman recorded three separate versions of “Body & Soul” between September 13 and October 10. The first was a rejected (and presumably lost) version featuring Don Howard on vocal. On September 19, they tried again with Frank Luther singing the alternate lyric. For the October 10 version, Reisman switched to a female vocalist, Frances Maddux, who sang the British lyric! No information has come down about just how Reisman learned about the lyric change or who made the last-minute switch on the arrangement, but it’s entirely possible that one of his orchestra members was playing in the pit orchestra for “Three’s A Crowd” and dutifully passed the word onto Reisman. But since it was the British lyric that Maddux sang and not the final standard version, it seems that the information came to Reisman se cond-hand, and no one realized that there were slight differences between the British and standard versions. Two other interesting tidbits about the Reisman recordings: they feature Reisman’s newly acquired trumpet soloist, Bubber Miley (which means that this was an early example of a racially-integrated band), and both the Luther and Maddux recordings of “Body & Soul” and “Something to Remember” were issued with the same Victor catalogue numbers. In his essay on “Body & Soul”, Will Friedwald theorizes that Victor did this to offer its audiences a choice between male and female vocals, but the original labels of both versions only state “with vocal refrain”. As far as I know, there are no copies of the Victor 78 with male vocals on one side and female vocals on the reverse.

cond-hand, and no one realized that there were slight differences between the British and standard versions. Two other interesting tidbits about the Reisman recordings: they feature Reisman’s newly acquired trumpet soloist, Bubber Miley (which means that this was an early example of a racially-integrated band), and both the Luther and Maddux recordings of “Body & Soul” and “Something to Remember” were issued with the same Victor catalogue numbers. In his essay on “Body & Soul”, Will Friedwald theorizes that Victor did this to offer its audiences a choice between male and female vocals, but the original labels of both versions only state “with vocal refrain”. As far as I know, there are no copies of the Victor 78 with male vocals on one side and female vocals on the reverse.

Of all the recordings of “Body & Soul” made during this period, none have been reissued and studied more than the October 9 recording by Louis Armstrong and His Sebastian New Cotton Club Orchestra. As he did with so many other songs during this period, Armstrong showed the world how to transform a popular song into a vehicle for artistic expression. And he did it by simply adapting the music into his own personal language. After an open trumpet introduction, Armstrong inserts a straight mute into his trumpet, which sets his melodic paraphrase in relief against the syrupy saxophones. He never strays far from the melody, but when he does, we sense the personality in his horn— the same that infuses his vocal chorus. And notice his vocal entrance: he elaborates on the simple syncopation of Green’s original by setting the first three notes on the off-beats. His loose interpretation of the lyrics (with minute variations in melody and rhythm) make the whole thing sound like a confessional instead of a set piece. Then in typical Armstrong fashion, he goes back to his horn and closes the arrangement with a grand flourish.

the same that infuses his vocal chorus. And notice his vocal entrance: he elaborates on the simple syncopation of Green’s original by setting the first three notes on the off-beats. His loose interpretation of the lyrics (with minute variations in melody and rhythm) make the whole thing sound like a confessional instead of a set piece. Then in typical Armstrong fashion, he goes back to his horn and closes the arrangement with a grand flourish.

It seems rather strange that recordings of “Body & Soul” ended abruptly shortly after the premiere of “Three’s A Crowd”. Other than a version by pianist/vocalist Seger Ellis (with both Dorsey brothers and Eddie Lang in the band) recorded on October 30 (with the standard lyrics) there was only a piano recording by Vee Lawnhurst and a piano roll by Robert Armbruster (both in November) and a big band version by Nat Star (undated) before Ambrose’s remake in October 1933. Of course, the Great Depression was in full force by then and record sales were plummeting. There were also issues with radio airplay, as the word body in the song’s title was strictly taboo, as was the word hell and the overtly sexual theme of the lyric. But thanks to superb recordings in the mid- to late-1930s by Henry “Red” Allen, Benny Goodman, Django Reinhardt, Art Tatum and the pairing of Chu Berry and Roy Eldridge, the song started to gain acceptance with jazz musicians. The floodgates opened with Coleman Hawkins’ 1939 recording (which ironically, only hinted at the melody in its opening bars before moving into Hawkins’ pure—and harmonically astute—improvisation.) Because of its wondrous chord changes, “Body & Soul” has become the testing piece for every generation of jazz musicians. It is also one of the great ballads, one that every vocalist must learn and master. And to return to where we started, it is a discography—this time, Tom Lord’s online “The Jazz Discography”—that has verified something that jazz fans have suspected all along: “Body & Soul” is the most recorded song in the jazz repertory with over 2200 existing recordings. That’s quite a song, Mr. Green.

Grateful acknowledgement to Gary Giddins, Will Friedwald, Ted Gioia and Jose Bowen whose pioneering research on “Body and Soul” made this article possible. The work of Libby Holman’s biographer Jon Bradshaw also offered important information on the backstage stories about “Three’s A Crowd”. Thanks to University of Northern Colorado’s music librarian Stephen Luttman for acting as my eyes with this hard-to-find volume.

And of course, many thanks to the discographers Brian Rust, Allen Debus, Ross Laird and Tom Lord for their meticulous work of documenting great jazz recordings.

The audio recordings embedded in this article are presented for educational and illustrative purposes. Jazz History Online neither owns nor controls the rights to these recordings. All rights belong to the original copyright holders.

THE RECORDINGS

Jack Hylton & His Orchestra (3:26)

PHILIPPE BRUN, JACK RAINE (tp); LEW DAVIS, LEO VAUCHANT (tb);CLEM LAWTON (tuba); E.O. “POGGY” POGSON, JOHNNY RAITZ, JOE CROSSMAN, NOEL “CHAPPIE” D’AMATO (r); BILLY TERNENT (r,arr); JOHNNY ROSEN, HUGO RIGNOLD (vln); HARRY BERLY (vla); PETER YORKE, BILLY MUNN (p); BILL HERBERT (bj); JIM MERRITT (b); BASIL WILTSHIRE (d); HARRY ROBBINS (perc); PAT O’MALLEY (v).

LONDON; 2/7/30.

Carroll Gibbons (3:18)

CARROLL GIBBONS (p). [ALL OTHERS UNKNOWN.]

LONDON; 2/19/30.

Ambrose & His Orchestra (4:00)

SYLVESTER AHOLA, GEORGE (or Dennis) RATCLIFFE (tp); TED HEATH (tb); DANNY POLO, JOE JEANETTE, JOE CROSSMAN (r); ERIC SIDAY, REG PURGSLOVE, ERNIE LEWIS (vln); BERT READ (p); JOE BRANNELLY (bj,g); DICK ESCOTT (b,tuba); MAX BACON (d); SAM BROWNE (v).

LONDON; 2/22/30.

Jack Hylton & His Orchestra (4:12)

PHILIPPE BRUN, JACK RAINE (tp); LEW DAVIS (tb); PAUL FENOULHET (tp,tb); CLEM LAWTON (tuba); E.O. “POGGY” POGSON, JOHNNY RAITZ, NOEL “CHAPPIE” D’AMATO, BILLY TERNENT, JOE CROSSMAN (r); JOHNNY ROSEN, HUGO RIGNOLD (vln); HARRY BERLY (vla); PETER YORKE, BILLY MUNN (p); SONNY FARRAR (bj); JIM MERRITT (b); BASIL WILTSHIRE (d); HARRY ROBBINS (perc); PAT O’MALLEY (v).

LONDON; 2/25/30.

Elsie Carlisle (with Jay Wilbur & His Orchestra) (3:08)

ELSIE CARLISLE (v) unknown (cl); ERIC SIDAY (vln); prob. BERT READ (p); JOE BRANNELLY (g).

LONDON; 3/30.

Spike Hughes & His Decca-Dents (3:09)

SYLVESTER AHOLA (tp); PHILIP BUCHEL (as,bs?); STAN ANDREWS (vln); EDDIE CARROLL (p); LESLIE SMITH (g); SPIKE HUGHES (b); VAL ROSING (d,v).

LONDON; 3/12/30.

Paul Whiteman & His Orchestra (3:07)

NAT NATOLI, HARRY GOLDFIELD, ANDY SECREST (tp,cor); HERB WINFIELD, BILL RANK (tb); JACK FULTON (tb,v); CHESTER HAZLETT, FUD LIVINGSTON, FRANK TRUMBAUER, CHARLES STRICKFADEN (r); KURT DIETERLE, MISCHA RUSSELL, MATTY MELNICK (vln); ROY BARGY (p); MIKE PINGATORE (bj); MIKE TRAFFICANTE (tuba); GEORGE MARSH (d).

NYC; 9/10/30.

Helen Morgan (with Leonard Joy & His Orchestra) (3:03)

HELEN MORGAN (v). [ALL OTHERS UNKNOWN.]

NYC; 9/12/30.

Fred Rich & His Orchestra (3:13)

BILL MOORE, BUNNY BERIGAN (tp); TOMMY DORSEY, JACK LACEY (tb); TONY PARENTI, FRED CUSICK (r); DICK ROBERTSON (v).

NYC; 9/17/30.

Leo Reisman & His Orchestra (3:03)

BUBBER MILEY, LOUIS SHAFFRIN, unknown (tp); ERNIE GIBBS, CHUCK CAMPBELL (tb); JESSE SMITH, LOUIS MARTIN, BURT WILLIAMS, BILL TRONSTEIN (r); LEO REISMAN, LEW CONRAD, unknown (vln); unknown (vlc); EDDIE DUCHIN (p); unknown (g); unknown (b); HARRY SIGMAN (d); FRANK LUTHER (v).

NYC; 9/19/30.

Ruth Etting (3:21)

RUTH ETTING (v). [ALL OTHERS UNKNOWN.]

NYC; 9/29/30.

Annette Hanshaw (3:05)

ANNETTE HANSHAW (v); BEN SELVIN (vln); R.H. BOWERS (p); STAN KING (d). [ALL OTHERS UNKNOWN.]

NYC; 10/7/30.

Libby Holman (3:18)

LIBBY HOLMAN (v). [ALL OTHERS UNKNOWN.]

NYC; c. 10/8/30.

Ozzie Nelson & His Orchestra (2:37)

CHARLIE SPIVAK (tp); unknown (tb); CHARLIE BUEBECK, DONALD WRIGHT, BILL NELSON (r); SID BROKAW, unknown (vln); HARRY MURPHY (p); SANDY WOLFE (g); FRED WHITESIDE (b); JOE BOHAN (d); OZZIE NELSON (v).

NYC; 10/8/30.

Louis Armstrong & His Sebastian New Cotton Club Orchestra (3:17) LOUIS ARMSTRONG (tp,v); GEORGE ORENDORFF, HAROLD SCOTT (tp); LUTHER CRAVEN (tb); LES HITE, MARVIN JOHNSON, CHARLIE JONES (r); HENRY PRINCE (p); BILL PERKINS (bj); JOE BAILEY (b); LIONEL HAMPTON (d).

LA; 10/9/30.

Leo Reisman & His Orchestra (2:50)

BUBBER MILEY, LOUIS SHAFFRIN, unknown (tp); ERNIE GIBBS, CHUCK CAMPBELL (tb); JESSE SMITH, LOUIS MARTIN, BURT WILLIAMS, BILL TRONSTEIN (r); LEO REISMAN, LEW CONRAD (vln); FRANCES MADDUX (vln,v); unknown (vlc); EDDIE DUCHIN (p); unknown (g); unknown (b); HARRY SIGMAN (d).

NYC; 10/10/30.

Seger Ellis (2:49)

TOMMY DORSEY (tb); JIMMY DORSEY (cl,as); SEGER ELLIS (p,v); EDDIE LANG (g). [ALL OTHERS UNKNOWN.]

|NYC; 10/30/30.