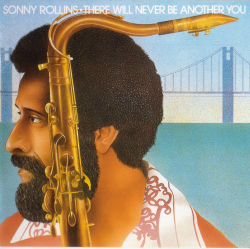

In the late 1950s, the top tenor saxophonists in modern jazz were Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane. The two men respected each other’s work and had even played together on a classic blues line, re-titled “Tenor Madness” for the occasion. As the decade came to a close, Rollins’ and Coltrane’s paths  diverged: Coltrane went through a tumultuous period of development, exploring in turn complex chord structures, modal music, and free jazz; Rollins took some time away from the jazz scene to study his horn and to work out his own approach to the avant-garde. Coltrane benefitted from Bob Thiele’s open-minded production ethic at Impulse Records. Thiele encouraged avant-garde experimentation, and Impulse offered big budgets, outstanding fidelity, striking gatefold album covers and excellent distribution. Since his return to the scene, Rollins had recorded for RCA Victor. Rollins’ RCA recordings were quite good overall, featuring collaborations with Coleman Hawkins, Jim Hall and Don Cherry, but his fame was being eclipsed by Coltrane. When Rollins’ RCA contract ended in 1964, he signed with Impulse. On June 17, 1965, Rollins performed an outdoor concert at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the performance was recorded as his initial Impulse project. For reasons discussed below, the album was not released for 13 years, when it was issued—with hideous packaging—as “There Will Never Be Another You.”

diverged: Coltrane went through a tumultuous period of development, exploring in turn complex chord structures, modal music, and free jazz; Rollins took some time away from the jazz scene to study his horn and to work out his own approach to the avant-garde. Coltrane benefitted from Bob Thiele’s open-minded production ethic at Impulse Records. Thiele encouraged avant-garde experimentation, and Impulse offered big budgets, outstanding fidelity, striking gatefold album covers and excellent distribution. Since his return to the scene, Rollins had recorded for RCA Victor. Rollins’ RCA recordings were quite good overall, featuring collaborations with Coleman Hawkins, Jim Hall and Don Cherry, but his fame was being eclipsed by Coltrane. When Rollins’ RCA contract ended in 1964, he signed with Impulse. On June 17, 1965, Rollins performed an outdoor concert at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the performance was recorded as his initial Impulse project. For reasons discussed below, the album was not released for 13 years, when it was issued—with hideous packaging—as “There Will Never Be Another You.”

Rollins seemed eager to make his mark. For the first and only time in his career, he hired two drummers. Coltrane would do the same a few months later for his album “Meditations”, but Rollins was clearly not interested in the overwhelming power of an Elvin Jones/Rashied Ali team, opting instead for two of the lightest-sounding drummers of the time, Billy Higgins and Mickey Roker. At the time, Higgins was praised for his dancing cymbal work on popular jazz boogaloos like Lee Morgan’s “Sidewinder” He was also the original drummer for Ornette Coleman’s quartet, and had played off and on with Rollins on RCA. Roker was already Rollins’ regular drummer, and had played on Rollins’ last two RCA albums (Many years later, Roker would become Connie Kay’s replacement in the Modern Jazz Quartet). The MoMA concert was covered by Down Beat, and the anonymous reviewer reported that during the performance, Rollins sometimes stood between the two drummers. But Rollins wasn’t staying in one place for long. Throughout the concert, he wandered all over the newly enlarged performing space. It must have been a wonderful experience for those who heard the concert live (and endured a constant light drizzle in the process), but it was probably very frustrating for the recording engineer, Rudy Van Gelder. In 1961, Van Gelder had famously crawled on hands and knees at the Village Vanguard to keep Coltrane on mike during an extended improvisation. In recognition of Van Gelder’s efforts, the track was issued as “Chasin’ the Trane”. Why Van Gelder didn’t do the same for Rollins is a mystery, but it might have been that Van Gelder expected Rollins to dutifully stand in front of the microphone and play. No such luck. Down Beat’s reviewer wrote that Rollins’ initial entrance was from behind a tree, playing “Will You Still Be Mine”. That portion of the concert didn’t make it on to the record, and it’s possible that Van Gelder hadn’t started his tape recorder when Rollins began to play. It was not the first time that Rollins had strolled around the stage while improvising—recently released recordings of Rollins at Ronnie Scotts’ from January 1965 find him going off-mike regularly—but the tapes from Scotts are in mono, and the MoMA recording is in stereo, so even though Rollins was frequently distant from the stationary mikes, we can at least sense where he was on stage.

And how he played! Supported by Tommy Flanagan’s piano, Bob Cranshaw’s bass and the two simpatico drummers, Rollins seems to burst with ideas. The opening chorus of “Green Dolphin Street” overflows with brilliant motives, and while Rollins seems eager to get everything out, his inner sense of structure keeps the solo organized and logical. When the band goes into a vamp near the end of the tune, Rollins inserts an extended quote of the old Fred Astaire chestnut, “The Continental”. The quote is so long that we expect a full version of the song. But instead everything dissipates. Rollins plays a short unaccompanied cadenza and then launches into another song of roughly the same vintage, “Three Little Words”. Rollins lets Flanagan and Cranshaw solo before he trades ideas with the drummers and then launches his own full solo. It’s not as well-executed as the version he recorded three weeks later (see below), but it generates a lot of heat before breaking down into another rarity, “Mademoiselle de Paris”. The second side’s opener, “To a Wild Rose” is probably the most conventional arrangement on the entire album, but Rollins starts wandering again, and as he moves his horn to and fro, the presence of his sound shifts dramatically. The 16-minute title track closes the album. After stating the theme, Rollins moves way off-mike, and for a while, it’s hard to tell whether he was planning to start his own solo or was just bouncing a few ideas off Flanagan. Eventually, Flanagan takes the lead for a couple of elegant choruses before yielding to Rollins, who not only takes off for an extended solo, but also abruptly changes the key midway through! Rollins engages the drummers for a lengthy series of four-bar exchanges, but just when we think he’s resuming his solo, he has Flanagan and Cranshaw drop out so he can play a chorus accompanied only by the drummers. Rollins’ ensuing solo cadenza evolves into a calypso, and when he gets back to “Another You”, he seems to close the performance with a long held note. The audience applauds, and that should be the end, but Rollins starts the tune again and soon after, walks off the stage. No one in the band seems to know what to do. Cranshaw starts to solo while a very distant Dan Morgenstern makes a post-concert announcement.

In hindsight, Rollins was experimenting with a loose structure which he would  eventually adopt for his concert performances. However, it’s easy to understand why Thiele and Van Gelder were disappointed in the recording. Although Van Gelder did an admirable job of balancing the instruments (the dual drummers are only overpowering on the title track) the MoMA recording was not very flattering to the company or the engineer, even for an outdoor live recording. The MoMA recording was left in the vault, and Rollins was invited to record an album at Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Rollins dropped the double drummer idea, retained Roker and replaced Flanagan and Cranshaw with Ray Bryant and Walter Booker. The music was still quite loose, with lots of interaction between the musicians, but Rollins stayed on mike and focused his ideas. The studio version of “Three Little Words” was a masterpiece of thematic improvisation, and the extended version of “Everything Happens To Me” is one of his best ballad interpretations. There’s also the delightful calypso, ”Hold ‘Em Joe” and a concise version of “Blue Room”. The studio album was issued as “Sonny Rollins on Impulse” and the latest CD reissue wisely combines it with the MoMA concert. It offers two contrasting sides of Rollins, each fascinating in its own way.

eventually adopt for his concert performances. However, it’s easy to understand why Thiele and Van Gelder were disappointed in the recording. Although Van Gelder did an admirable job of balancing the instruments (the dual drummers are only overpowering on the title track) the MoMA recording was not very flattering to the company or the engineer, even for an outdoor live recording. The MoMA recording was left in the vault, and Rollins was invited to record an album at Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Rollins dropped the double drummer idea, retained Roker and replaced Flanagan and Cranshaw with Ray Bryant and Walter Booker. The music was still quite loose, with lots of interaction between the musicians, but Rollins stayed on mike and focused his ideas. The studio version of “Three Little Words” was a masterpiece of thematic improvisation, and the extended version of “Everything Happens To Me” is one of his best ballad interpretations. There’s also the delightful calypso, ”Hold ‘Em Joe” and a concise version of “Blue Room”. The studio album was issued as “Sonny Rollins on Impulse” and the latest CD reissue wisely combines it with the MoMA concert. It offers two contrasting sides of Rollins, each fascinating in its own way.

Rollins recorded two more albums for Impulse, his original score for the film “Alfie” and a thrilling quartet album, “East Broadway Run-Down”. In 1968, he left the jazz scene, and did not record again until he signed with Milestone in 1972.The eventual release of the MoMA concert in 1978 was greeted with much critical griping about the sound, even though it was an important document of Rollins’ concert presentations. Rollins returned to MoMA just over 20 years later to record his first unaccompanied solo concert. By this time, Rollins had fitted his saxophone with a microphone so he could move about as he wished and still be heard. At long last, the technology had caught up with the artist!