On July 31, 2014, The New Yorker posted a now-infamous article on their website called “Sonny Rollins: In His Own Words”. Ascribed to a “Django Gold”, the article purported to tell Rollins’ dissatisfaction with jazz and his life in general. The piece was written in first-person style without any indication of when the supposed interview took place, or why Rollins was spouting opinions that were completely opposite from his previous interviews. I found the article through a Facebook link on the morning of August 1, and my immediate reaction was that Rollins might be suffering from depression. From experiences within my circle of friends, my family and my own struggles, I knew that clinical depression could be far more lethal than drugs or alcohol.

On July 31, 2014, The New Yorker posted a now-infamous article on their website called “Sonny Rollins: In His Own Words”. Ascribed to a “Django Gold”, the article purported to tell Rollins’ dissatisfaction with jazz and his life in general. The piece was written in first-person style without any indication of when the supposed interview took place, or why Rollins was spouting opinions that were completely opposite from his previous interviews. I found the article through a Facebook link on the morning of August 1, and my immediate reaction was that Rollins might be suffering from depression. From experiences within my circle of friends, my family and my own struggles, I knew that clinical depression could be far more lethal than drugs or alcohol.

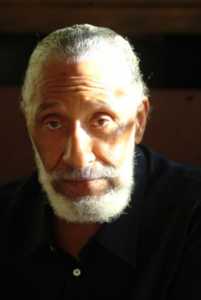

As it turned out, the article was a hoax, the author was a writer for The Onion, and Rollins was unaware of the piece. On the evening of August 4, Rollins held a live webcast which effectively debunked the entire article. The saxophonist, decked out like the world’s hippest Santa Claus with a red shirt, white hair and dark glasses, exhibited his familiar Zen-like approach to music and life. Naturally, he recognized the article was satire from the start, and his initial concern was not about his own well-being, but to jazz students who might read the falsely attributed quotes and question their own motives in studying the music. Rollins also claimed that the article was part of a continuing attempt by the press to kill jazz. Later, he reassured his followers that jazz is more than music; it is a creative spirit that cannot be quashed.

It took The New Yorker three days to put up a clarification that the article was indeed a satire Gold tried to make amends by tweeting how much he loved Rollins (and jazz pianist Roberta Picket wrote a brilliant essay, also in faux-first-person, of Gold trying to prove his own hipness). While many in the jazz world fretted about how The New Yorker had fallen so low both in the humor and jazz departments, another article turned up in the Washington Post. Even after claiming that the piece was not satire, it went down the same path as The New Yorker article, trashing the jazz tradition and its iconic performers with giddy abandon. Within a few days, a rebuttal post by a more knowledgeable member of the Post staff and another by a working musician seemed to offer the author his comeuppance.

Yet many of us were wondering just what was supposed to be so funny about these pieces. As Rollins correctly noted, jazz is full of humor. Most jazz humor is directed back towards the music, either by poking fun at a silly piece of pop music, or by inserting quotes of other songs or solos within improvisations (jazz’s version of a non-sequitur). As I’ve written in this column, comedians like Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce and Bill Cosby have occasionally included jazz-related material in their standup routines and talk show patter. And recently, the music business has taken a few jabs through the videos of singer Sara Gazarek. So it’s not that the jazz world can’t take a joke. We just get a little upset when an outsider trashes our beloved art form. But there was something more mean-spirited about Gold’s piece. It took a seemingly unrelated event to bring that element into focus.

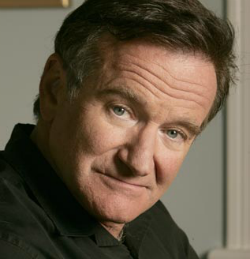

Sometime between 10:30pm Sunday August 10 and 11:45am Monday August  11, Robin Williams took his own life. The brilliant comedian and actor had suffered from depression for many years, and while he seemed to have an idyllic life with artistic and personal successes, something deep inside Williams’ mind told him that his life was not worth living. Many obituaries compared Williams’ stream-of-conscious comic style with jazz improvisation, and several fans and colleagues said that Williams was a jazz fan. Guitarist Diego Figueiredo posted a photo of Williams backstage at one of his gigs; Erin Michelle Threlfall, who once worked as a waitress in a New York jazz club recalled that Williams was a fairly regular customer; and John Schaefer noted that Williams had hired Bobby McFerrin as his opening act because Williams recognized that both he and McFerrin had similar approaches to interacting with a live audience. Williams had also recorded with McFerrin (“Beverly Hills Blues” came from a concert where Williams spontaneously joined McFerrin onstage), and Williams had once considered a recording project where his comic riffing would be juxtaposed against jazz improvisation.

11, Robin Williams took his own life. The brilliant comedian and actor had suffered from depression for many years, and while he seemed to have an idyllic life with artistic and personal successes, something deep inside Williams’ mind told him that his life was not worth living. Many obituaries compared Williams’ stream-of-conscious comic style with jazz improvisation, and several fans and colleagues said that Williams was a jazz fan. Guitarist Diego Figueiredo posted a photo of Williams backstage at one of his gigs; Erin Michelle Threlfall, who once worked as a waitress in a New York jazz club recalled that Williams was a fairly regular customer; and John Schaefer noted that Williams had hired Bobby McFerrin as his opening act because Williams recognized that both he and McFerrin had similar approaches to interacting with a live audience. Williams had also recorded with McFerrin (“Beverly Hills Blues” came from a concert where Williams spontaneously joined McFerrin onstage), and Williams had once considered a recording project where his comic riffing would be juxtaposed against jazz improvisation.

The fact that Robin Williams was—in an admittedly small way—part of the jazz world brought me back to Gold’s article. Thankfully, Sonny Rollins wasn’t suffering from depression, but Williams certainly was. Was clinical depression the real target of Gold’s satire? This fake Rollins quote certainly sounds like the thoughts of a depressive: I really don’t know why I keep doing this. Inertia, I guess. Once you get stuck in a rut, it’s difficult to pull yourself out, even if you hate every minute of it. Maybe I’m just a coward. (That last word makes me cringe, as a Fox News contributor called Williams a coward for committing suicide). And how about this knee-slapper: There was this one time, in 1953 or 1954, when a few guys and I had just finished our last set at Club Carousel, and we were about to pack it in when in walked Bud Powell and Charlie Parker. We must have jammed together for five more hours, right through sunrise. That was the worst day of my life. Perhaps Gold finds it hilarious that a respected artist could be disappointed with his own life, even when there is abundant evidence to refute that belief? When Robin Williams asphyxiated himself, he showed that some successful artists do indeed hold that belief. Whether or not he intended for his death to be a final message to the world, Williams reminded us all that depression is no laughing matter. We should have remembered that a few days earlier.