The Rodney/Sullivan group became one the most popular groups in jazz. They toured extensively, and by the following summer, Rodney told Richard Sudhalter that for the first time in his career he was exhausted, and longed for a few days off. The end was nowhere in sight, with the band being booked two years in advance. It’s not hard to imagine how Sullivan reacted to the touring schedule. His family had expanded during his time in Florida, and he felt a strong responsibility to be at home with his wife and children. Still, the group soldiered on.

When they entered Nola Studios in New York in June 1981 to record Rodney’s Muse album, “Night and Day”, they had six arrangements to record, along with a new bassist and drummer. Barry Smith had a very short tenure with the band (his permanent replacement, Jay Anderson, was in place by September). Sullivan replaced Tom Whaley with a friend from Florida, Steve Bagby, and his stay continued a few months longer until Jeff Hirshfield took over. The album commences with a fast-tempo jaunt through “Night and Day”. Sullivan plays well-articulated bebop alto over the surging rhythm, and Rodney follows suit in his flugelhorn solo. Dial introduces quartal patterns in his solo, but it’s back to bebop for the exchanges, final theme, and vamp. “You Leave Me Breathless” opens with a soprano/piano duet on the theme in rubato time. The rhythm section comes in under Rodney’s flugel on the bridge, with Sullivan taking the final eight. Just as it ends, the two horns intertwine in an arching duet which introduces Rodney’s solo. These short duets turn up all over the Rodney/Sullivan arrangements and they are refreshing contrasts to the typical jazz combo timbres. As Rodney and Sullivan alternate short solos in this fine arrangement, the duets become the unifying element of the performance. Jeff Meyer’s “Babies” was inspired by a sudden population explosion amongst his friends. Rodney and Sullivan both play trumpets, and as Rodney admits in the notes, their solo styles are still quite similar. The piece features another trumpet chase, but this one is tempered by a much more reasonable medium-fast tempo. Dial’s chorus sparkles with brilliant inventions, and Smith’s solo is fine, if not particularly memorable. Bagby is a good foil for the horns, and he seems less intrusive than his predecessor. “Muck and Meyer” was first presented to the group at this session. A medium blues, it offered few challenges and ample inspiration to the quintet. Sullivan explores the edges of blues harmony in his alto solo, but Rodney plays pretty on flugelhorn. As the two horns alternate solos, Sullivan intensifies his tone to influence the approach of his co-leader, but Rodney remains unflappable. “Frito Mistos” was named after an after-work meal enjoyed by the younger members of the band. The title has nothing to do with the song, which features a harmonic obstacle course that moves through several keys. Rodney said that his biggest challenge was keeping track of the tonality, as the lead sheet did not mark the shifting key signatures. As the horn solos consisted of eight-bar exchanges between Sullivan’s trumpet and Rodney’s flugelhorn, it may have been a bigger struggle in that form than if they had played full solos. “Dial-A-Brew” was a staple of the quintet’s repertoire (although no live versions have surfaced). Red and Ira both play trumpet here, and as on the live versions of “Red Arrow”, Sullivan solos with only the drums in accompaniment. While the harmonies were again difficult, Rodney and Sullivan felt comfortable enough with them to soar through their chase sequence. Bagby’s drum solo takes up a couple of minutes, but Dial’s chart maintains listener interest by including short ensemble passages at various points in the solo.

When they entered Nola Studios in New York in June 1981 to record Rodney’s Muse album, “Night and Day”, they had six arrangements to record, along with a new bassist and drummer. Barry Smith had a very short tenure with the band (his permanent replacement, Jay Anderson, was in place by September). Sullivan replaced Tom Whaley with a friend from Florida, Steve Bagby, and his stay continued a few months longer until Jeff Hirshfield took over. The album commences with a fast-tempo jaunt through “Night and Day”. Sullivan plays well-articulated bebop alto over the surging rhythm, and Rodney follows suit in his flugelhorn solo. Dial introduces quartal patterns in his solo, but it’s back to bebop for the exchanges, final theme, and vamp. “You Leave Me Breathless” opens with a soprano/piano duet on the theme in rubato time. The rhythm section comes in under Rodney’s flugel on the bridge, with Sullivan taking the final eight. Just as it ends, the two horns intertwine in an arching duet which introduces Rodney’s solo. These short duets turn up all over the Rodney/Sullivan arrangements and they are refreshing contrasts to the typical jazz combo timbres. As Rodney and Sullivan alternate short solos in this fine arrangement, the duets become the unifying element of the performance. Jeff Meyer’s “Babies” was inspired by a sudden population explosion amongst his friends. Rodney and Sullivan both play trumpets, and as Rodney admits in the notes, their solo styles are still quite similar. The piece features another trumpet chase, but this one is tempered by a much more reasonable medium-fast tempo. Dial’s chorus sparkles with brilliant inventions, and Smith’s solo is fine, if not particularly memorable. Bagby is a good foil for the horns, and he seems less intrusive than his predecessor. “Muck and Meyer” was first presented to the group at this session. A medium blues, it offered few challenges and ample inspiration to the quintet. Sullivan explores the edges of blues harmony in his alto solo, but Rodney plays pretty on flugelhorn. As the two horns alternate solos, Sullivan intensifies his tone to influence the approach of his co-leader, but Rodney remains unflappable. “Frito Mistos” was named after an after-work meal enjoyed by the younger members of the band. The title has nothing to do with the song, which features a harmonic obstacle course that moves through several keys. Rodney said that his biggest challenge was keeping track of the tonality, as the lead sheet did not mark the shifting key signatures. As the horn solos consisted of eight-bar exchanges between Sullivan’s trumpet and Rodney’s flugelhorn, it may have been a bigger struggle in that form than if they had played full solos. “Dial-A-Brew” was a staple of the quintet’s repertoire (although no live versions have surfaced). Red and Ira both play trumpet here, and as on the live versions of “Red Arrow”, Sullivan solos with only the drums in accompaniment. While the harmonies were again difficult, Rodney and Sullivan felt comfortable enough with them to soar through their chase sequence. Bagby’s drum solo takes up a couple of minutes, but Dial’s chart maintains listener interest by including short ensemble passages at various points in the solo.

One special performance from the summer of 1981 deserves mention here, even though we have only the recollections of jazz musician and author Richard Sudhalter, who described the moment in the liner notes to “Night and Day”.

They looked very small, the two of them, and just a mite lonely walking out all by themselves on the stage of Carnegie Hall. Just a couple of guys, Mutt and Jeff with trumpets, alone in all that space. The capacity audience sat up, expectant. To be sure, this was a duet evening, highlight of the 1981 Kool Jazz Festival. There had been a pair of guitars, a voice-and-piano episode, and John Lewis and Milt Jackson, 50% of the Modern Jazz Quartet, yet to come. Two trumpets, though, were another matter: no rhythm section, no piano or even bass. What kind of music did these two expect to make? An answer wasn’t long in coming. On stage, Red Rodney—short, rubicund, energetic—exchanged a glance with tall, woodsman-rangy Ira Sullivan. Without further preamble or communication, they slammed together, micrometer-precise into “The Red Arrow”, a fast and furious bebop variant originally recorded by Red and Ira in 1955 [sic: 1957]. No support was needed: the two horns climbed and plunged and swooped, tones ringing in the stillness. They were, by turns, children cavorting at play, jets diving through a clear morning sky. Switching to flugelhorns, they filled the air with lullabies, elegies and odes. At the last, Ira took up his alto flute to end it with a quiet hymn. Appropriately, in that this twenty minutes was for both men an act of celebration and self-consecration in response to unprecedented good fortune.

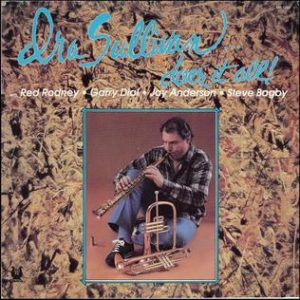

In September 1981, the band spent several days in the studio: the 14th at Nola for the Muse LP, “Ira Sullivan…Does It All” and the 21st-24th at CBS for Elektra-Musician’s “Spirit Within”. The albums represent considerably different approaches, with Sullivan’s album focusing on classic pop ballads and progressive jazz standards, and the Elektra-Musician completely dedicated to originals by Dial, Sullivan, and Meyer. The personnel (with Jay Anderson now on bass) is stable, with one notable exception: bassoonist Michael Rabinowitz is added on the second side of the Sullivan album.

“Amazing Grace”, set at the end of the Muse LP’s first side, became one of the most divisive pieces in the group’s repertoire. On Ira’s insistence, “Grace” closed most of the Rodney/Sullivan concerts. At least two members of the band were Jewish, so the tune choice was troubling in itself, but the bigger problem (which developed over the remaining years of the band) was Ira’s penchant for preaching on the bandstand. This practice caused several problems, including many complaints from audience members. Dial recalls one German patron who slammed his fist on the table before shouting to Ira, “Just play the Goddamned music!” As for “Amazing Grace”, the band created a beautiful aired-out setting for the album, which featured at least three overdubbed soprano lines over a sustained rhythm background. The song appears on two concert tapes, but only one is complete.

“Sovereign Court” by Florida bassist Lou Berryman was as riveting an opener for Sullivan’s album as Walrath’s “Lodgellian Mode” was for the first Vanguard LP. In three-and-a-half minutes, it offers a quick-paced introduction to the band with dual flugelhorns intoning the fanfare-like theme, brilliant solos on flugel (Sullivan) and trumpet (Rodney), splashing colors from Dial’s keyboard, virtuosic bass from Anderson, and thrilling drums from Bagby. A medium tempo setting of “The More I See You” showcases Ira’s soprano, but Anderson overdubbed a second arco line over his pizzicato part, which provided a dramatic counterpoint to the straight horn. Sullivan returns to Ellington for his ballad feature, “Prelude to a Kiss”, played as a duet for flugelhorn and piano. The old show tune “Together” reunites Red and Ira for a high-spirited dual improvisation on flugel and alto. The duet idea continues as Red drops out, and Dial joins in the collective interplay. Sullivan continues playing after Dial stops, leaving a stunning trio musical conversation of soprano, bass, and drums. There is a little time for Anderson and Bagby to interact on their own before the closing theme returns (with an appropriate Sondheim quote). The album’s flip side features extended versions of Coltrane’s “Central Park West” and Hancock’s “Dolphin Dance”. On “Central”, Sullivan takes the tempo a little quicker than the composer and harmonizes the melody for the three horns (flugel, soprano, and bassoon). Sullivan soars in his solo over a background that shifts between 3/4 and 4/4 time, and Rodney plays over a swing beat that occasionally references the previous ambiguous rhythms. Sullivan plays an impassioned alto solo before the rhythm loosens again for Dial’s chiming solo. Rabinowitz, then a fresh new face on the New York jazz scene, plays a well-constructed solo that on its own nearly legitimizes his instrument as a jazz horn! “Dolphin Dance” returns with the same rubato opening (now expanded for the entire sextet), but the up-tempo blowing section is now in swing time, rather than Latin. Sullivan remains on alto for another powerful solo (with brief ensemble interludes again marking the solo phrases). Rodney feels very comfortable with this piece, as his phrases glide over the harmony. Rabinowitz seems tied to the ground beat, and it sounds like he’s trying to force-feed bebop onto the song. A later Sullivan/Bagby episode sounds like bebop exchanges at the start but eventually becomes more free-flowing in phrase lengths and lines.

opener for Sullivan’s album as Walrath’s “Lodgellian Mode” was for the first Vanguard LP. In three-and-a-half minutes, it offers a quick-paced introduction to the band with dual flugelhorns intoning the fanfare-like theme, brilliant solos on flugel (Sullivan) and trumpet (Rodney), splashing colors from Dial’s keyboard, virtuosic bass from Anderson, and thrilling drums from Bagby. A medium tempo setting of “The More I See You” showcases Ira’s soprano, but Anderson overdubbed a second arco line over his pizzicato part, which provided a dramatic counterpoint to the straight horn. Sullivan returns to Ellington for his ballad feature, “Prelude to a Kiss”, played as a duet for flugelhorn and piano. The old show tune “Together” reunites Red and Ira for a high-spirited dual improvisation on flugel and alto. The duet idea continues as Red drops out, and Dial joins in the collective interplay. Sullivan continues playing after Dial stops, leaving a stunning trio musical conversation of soprano, bass, and drums. There is a little time for Anderson and Bagby to interact on their own before the closing theme returns (with an appropriate Sondheim quote). The album’s flip side features extended versions of Coltrane’s “Central Park West” and Hancock’s “Dolphin Dance”. On “Central”, Sullivan takes the tempo a little quicker than the composer and harmonizes the melody for the three horns (flugel, soprano, and bassoon). Sullivan soars in his solo over a background that shifts between 3/4 and 4/4 time, and Rodney plays over a swing beat that occasionally references the previous ambiguous rhythms. Sullivan plays an impassioned alto solo before the rhythm loosens again for Dial’s chiming solo. Rabinowitz, then a fresh new face on the New York jazz scene, plays a well-constructed solo that on its own nearly legitimizes his instrument as a jazz horn! “Dolphin Dance” returns with the same rubato opening (now expanded for the entire sextet), but the up-tempo blowing section is now in swing time, rather than Latin. Sullivan remains on alto for another powerful solo (with brief ensemble interludes again marking the solo phrases). Rodney feels very comfortable with this piece, as his phrases glide over the harmony. Rabinowitz seems tied to the ground beat, and it sounds like he’s trying to force-feed bebop onto the song. A later Sullivan/Bagby episode sounds like bebop exchanges at the start but eventually becomes more free-flowing in phrase lengths and lines.

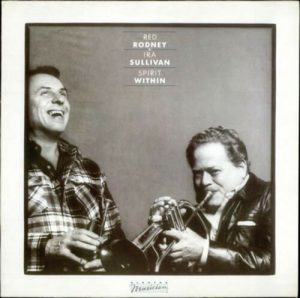

The Elektra-Musician LP, “Spirit Within” represents an alternative approach to repertoire. The four Garry Dial originals which encompass the first two-thirds of the album display a considerable change of direction. While the opening of “Sophisticated Yenta” could be considered a slow-motion fanfare—as compared to “Sovereign Court”— the sensuous medium bossa feel of the main tune and the warm glow of Sullivan’s alto flute solo felt more luscious than anything the band had played before. “King of France” included a flugelhorn chase, but Dial’s setting brought poise to the episode instead of a general free-for-all. The title track, introduced with Bagby’s exquisite cymbal solo, leads to a highly intense theme statement by muted trumpet and soprano sax which is spine-chilling. The engaging “Island Song” became another signature piece for the group with a delicious Latin groove, fine contrasting solos from flugel and soprano, an exotic percussion interlude, and superb collective improvising over the final vamp. Gary Giddins complained that Dial’s originals were “pedantic and un-swinging” and that they “overwhelm the interpreters”. Frankly, I cannot agree. Rodney and Sullivan were both eager to expand their repertoire. Implied within that goal is the knowledge that different music carries different rules. It wasn’t bebop (and perhaps it didn’t even have a name) but it was still jazz, albeit with different characteristics. These compositions deserved to be evaluated on their own terms, rather than being unfairly compared to bebop flag-wavers. “Monday’s Dance”, which represented common ground between Sullivan and Dial, was the logical choice to follow the pianist’s works. The arrangement was tightened up, but the tender opening and the interweaving flugelhorn lines remained, enhanced with a revitalized and joyous waltz groove. And with the presence of Jeff Meyer’s burning original “Crescent City”, Red and Ira showed that they hadn’t abandoned bebop at all. The intro on the New Orleans hymn “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” was a clever deception, as the main tune is pure unadulterated bop. The flugelhornists chase each other with glee over the burning rhythm section, the interplay between Dial and Bagby is highly charged, and Anderson’s bass lines swing with profound richness.

The Elektra-Musician LP, “Spirit Within” represents an alternative approach to repertoire. The four Garry Dial originals which encompass the first two-thirds of the album display a considerable change of direction. While the opening of “Sophisticated Yenta” could be considered a slow-motion fanfare—as compared to “Sovereign Court”— the sensuous medium bossa feel of the main tune and the warm glow of Sullivan’s alto flute solo felt more luscious than anything the band had played before. “King of France” included a flugelhorn chase, but Dial’s setting brought poise to the episode instead of a general free-for-all. The title track, introduced with Bagby’s exquisite cymbal solo, leads to a highly intense theme statement by muted trumpet and soprano sax which is spine-chilling. The engaging “Island Song” became another signature piece for the group with a delicious Latin groove, fine contrasting solos from flugel and soprano, an exotic percussion interlude, and superb collective improvising over the final vamp. Gary Giddins complained that Dial’s originals were “pedantic and un-swinging” and that they “overwhelm the interpreters”. Frankly, I cannot agree. Rodney and Sullivan were both eager to expand their repertoire. Implied within that goal is the knowledge that different music carries different rules. It wasn’t bebop (and perhaps it didn’t even have a name) but it was still jazz, albeit with different characteristics. These compositions deserved to be evaluated on their own terms, rather than being unfairly compared to bebop flag-wavers. “Monday’s Dance”, which represented common ground between Sullivan and Dial, was the logical choice to follow the pianist’s works. The arrangement was tightened up, but the tender opening and the interweaving flugelhorn lines remained, enhanced with a revitalized and joyous waltz groove. And with the presence of Jeff Meyer’s burning original “Crescent City”, Red and Ira showed that they hadn’t abandoned bebop at all. The intro on the New Orleans hymn “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” was a clever deception, as the main tune is pure unadulterated bop. The flugelhornists chase each other with glee over the burning rhythm section, the interplay between Dial and Bagby is highly charged, and Anderson’s bass lines swing with profound richness.

In November, the quintet (with Jeff Hirshfield replacing Bagby) toured Europe. On the 8th, their set at the Berlin Jazz Festival was broadcast over West German Radio. Hirshfield opens the concert with a roll on a very large gong (where did he find that instrument?) before the flugels begin “Just a Closer Walk”. As before, they segue into “Crescent City”, and while the tempo cooks, it is actually a little slower than the LP version. Rodney and Sullivan switch to trumpets for the fiery chase. On Dial’s solo, Anderson is the active partner in the interplay, and the bass solo employs double-stops to great advantage. Hirshfield’s fine drum solo accentuates how quickly he discovered and locked into the rhythm section’s groove. Next, the band premieres Sullivan’s arrangement of Herbie Hancock’s “Speak Like a Child”. This setting is quite faithful to the composer’s original Blue Note recording, and it provides an extended showcase for Sullivan’s alto flute. Rodney provides a trumpet obbligato which gradually morphs into a collective improvisation over a long meter feel anchored by Anderson. Sullivan continues after Rodney drops out (and with just over six minutes of continuous improvising, Sullivan deserves praise for creativity and endurance!) Dial contributes a gorgeous solo which subtly changes the feel before the trumpets return to the melody. Following the rhythm section’s improvisation on a vamp, Sullivan returns on flute and finds the way to “On a Clear Day”, played in its entirety as a duet with Dial. Suddenly, the rhythm picks up a fast tempo for “Babies” and Sullivan makes the switch to trumpet in just under 9 seconds (did anyone ever tell him that feat is theoretically impossible?) Clearly, the constant work had built up both trumpeter’s embouchures and, in the exchanges, they match each other on every step. Dial blazes away as the rhythm churns and boils. Anderson provides another jaw-dropping display of virtuosity before the trumpets engage Hirschfield for a chorus of exchanges. Over the final chord, both trumpets quote the “Clear Day” motive. “Island Song” appears next, newly outfitted with an extended opening vamp (with room for both horns to improvise), a collective solo chorus, and a piano solo with backgrounds alternating between Latin and rock. Rodney spreads warmth with his solo, and Sullivan’s soprano and Anderson’s bass converse as an old Miles Davis funk riff emerges from the rhythm section. A stunning transformation for this song only six weeks after its initial recording (with another drummer, no less!) After Anderson retunes his instrument, the band rips into an insanely-fast version of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Bebop”. Sullivan (on alto) and Rodney (trumpet) exchange half-choruses before improvising together. A quote from “Things to Come”—itself a transformation of “Bebop”—introduces Hirshfield’s crackling drum solo. Sullivan and Rodney eventually improvise over the drum accompaniment before charging back into the main theme. “Monday’s Dance” acts as an encore, with Sullivan’s flugelhorn calming the crowd. Red continues the effect with his theme statement. Within the exchanges, it sounds like Ira (and Red too?) switch from flugel to trumpet. The change in timbre is noticeable, although both Red and Ira could emit very bright sounds from their flugelhorns.

At this point, new recordings of the Red Rodney/Ira Sullivan Quintet become rather sparse. The public was still getting their records, of course: “Night and Day” was released in 1981, “Spirit Within” early the next year, “Ira Sullivan Does It All”, “Modern Music from Chicago” and “Sprint” (discussed below) in 1983, and the final two volumes of the Village Vanguard recordings in 1984 and 1986. However, there are no new broadcasts or recordings until November of 1982, a full year after Berlin. The band personnel was still intact when Elektra-Musician recorded them at New York’s Jazz Forum for their final commercial album “Sprint”. Jay Anderson’s solo bass opens “How Do You Know”, a Dial original that blossoms with every instrument’s entrance. Following Sullivan’s rubato alto flute (supported by Dial) and an assured tempo jump to a buoyant medium pace, Rodney displays outstanding technique and sensitive melodic direction. Sullivan answers with a passionate statement on alto sax followed by Dial, who restates his theme in dense block chords over turbulent rhythms by Anderson and Hirshfield. The final theme leads to a lovely coda in parallel harmony for alto sax and trumpet. One of the group’s regular tour stops was Rick’s Café Americain, a Chicago jazz club designed in the style of the saloon in “Casablanca”. Inspired by both the club and the movie, the band’s newest ballad feature was the film’s love theme, “As Time Goes By”. Ira starts the melody on alto sax, with Rodney taking the next eight bars on flugel, all accompanied by Dial’s solo piano. Ira returns for the bridge, noodles a little when Red returns, and finally joins him in a unison statement. The rest of the rhythm section joins in the second chorus, as the solos follow the same order as before. Rodney seems a little sentimental on this piece, but Sullivan whimsically adds a quote from “Petrushka” to add levity. The album’s title track, composed by Dial, is one of the most exciting recordings in the quintet’s discography. It was inspired by the music of Ornette Coleman, who appeared at the club on the night this piece was recorded. Coleman later said, “It was strange to walk in and hear myself”. Indeed, the swift melody resembles Coleman’s writing and Sullivan’s alto bears a striking resemblance to Ornette’s tone. Sullivan quotes a Coleman lick from “Free Jazz” and Rodney’s solo, which floats above the quick pulse, reveals that he had listened and learned from Coleman’s trumpeter Don Cherry. A bouncy swing groove with collective blowing by alto and trumpet yields to another fast episode as Dial flies all over the keyboard. Hirshfield commands attention in his drum solo—his development since Berlin is astounding—and he provides direction as the tune makes its final appearance. “My Son, the Minstrel” is a curious Dial composition with the pianist playing in stride style supporting Rodney as he moves effortlessly from bop to progressive styles. “Speak Like a Child” is the closer, with Ira weaving gorgeous melodies from his alto flute for the first half of the arrangement. Rodney now starts the long meter section with a trigger motive, and Anderson follows the collective improvisation with a lovely arco solo. Dial’s quiet solo refers back to the original melody before Anderson and Hirshfield join him in a long crescendo to bring back the flugelhorns. The coda features mournful phrases from both flugels and alto flute before settling into a final cadence.

jump to a buoyant medium pace, Rodney displays outstanding technique and sensitive melodic direction. Sullivan answers with a passionate statement on alto sax followed by Dial, who restates his theme in dense block chords over turbulent rhythms by Anderson and Hirshfield. The final theme leads to a lovely coda in parallel harmony for alto sax and trumpet. One of the group’s regular tour stops was Rick’s Café Americain, a Chicago jazz club designed in the style of the saloon in “Casablanca”. Inspired by both the club and the movie, the band’s newest ballad feature was the film’s love theme, “As Time Goes By”. Ira starts the melody on alto sax, with Rodney taking the next eight bars on flugel, all accompanied by Dial’s solo piano. Ira returns for the bridge, noodles a little when Red returns, and finally joins him in a unison statement. The rest of the rhythm section joins in the second chorus, as the solos follow the same order as before. Rodney seems a little sentimental on this piece, but Sullivan whimsically adds a quote from “Petrushka” to add levity. The album’s title track, composed by Dial, is one of the most exciting recordings in the quintet’s discography. It was inspired by the music of Ornette Coleman, who appeared at the club on the night this piece was recorded. Coleman later said, “It was strange to walk in and hear myself”. Indeed, the swift melody resembles Coleman’s writing and Sullivan’s alto bears a striking resemblance to Ornette’s tone. Sullivan quotes a Coleman lick from “Free Jazz” and Rodney’s solo, which floats above the quick pulse, reveals that he had listened and learned from Coleman’s trumpeter Don Cherry. A bouncy swing groove with collective blowing by alto and trumpet yields to another fast episode as Dial flies all over the keyboard. Hirshfield commands attention in his drum solo—his development since Berlin is astounding—and he provides direction as the tune makes its final appearance. “My Son, the Minstrel” is a curious Dial composition with the pianist playing in stride style supporting Rodney as he moves effortlessly from bop to progressive styles. “Speak Like a Child” is the closer, with Ira weaving gorgeous melodies from his alto flute for the first half of the arrangement. Rodney now starts the long meter section with a trigger motive, and Anderson follows the collective improvisation with a lovely arco solo. Dial’s quiet solo refers back to the original melody before Anderson and Hirshfield join him in a long crescendo to bring back the flugelhorns. The coda features mournful phrases from both flugels and alto flute before settling into a final cadence.

No recordings—commercial, broadcast, or private—have surfaced of the Rodney/Sullivan quintet for the entire year of 1983. Rodney did not enter a recording studio again until January 1984, when he collaborated with Charles Rouse on the Uptown album “Social Call”. Sullivan recorded albums in LA and Miami in 1983, but none of the rhythm section recorded that year. No one seems to know why this happened: from all indications, the band was still together and playing engagements. Clearly, this group’s music developed on the bandstand, and it is a pity that there are no further complete recordings chronicling the evolution of pieces like “Sprint”, “Amazing Grace” and the “Greensleeves”/“Giant Steps” medley.

The next available broadcast of the Rodney/Sullivan quintet comes from the Montreal Jazz Festival in a performance recorded July 3, 1984, and probably broadcast sometime later that year. The program begins with the “Greensleeves” medley. Sullivan intones the ancient tune on soprano with dramatic punctuations from bass and drums between the phrases. Rodney plays a melancholy flugel solo over the moderate waltz tempo, and Sullivan blows long singing phrases on soprano. Anderson plays an intriguing line under a brief collective improv by the horns, then continues his commentary under Dial’s sunny piano solo. Hirshfield plays a very musical drum solo which leads directly into a 3/4 reading of “Giant Steps”. Sullivan and Rodney tackle the notorious changes and then move into a chorus of exchanges, which alternates between 3/4 and 4/4. Ira thanks the audience and it sounds like he’s about to announce the next tune, but a tape splice silences him and moves us directly into “King of France”. In the trumpet exchange, Rodney breezes through the changes, with Sullivan chasing at his heels. The length of the exchange phrases breaks down and soon the two trumpets are improvising together. So much for the poised duet of the LP version! Dial gets a chorus in before the trumpets return to announce Hirshfield’s powerhouse solo. The coda quotes “La Marseillaise”, and Dial transitions to “Speak Like a Child”. The opening chorus is now a free-time dialogue between alto flute and arco bass, with incidental commentary from piano and wind chimes. The alto flute solo chorus is similar to earlier versions, but the rhythmic feel has been de-emphasized to create a peaceful atmosphere. Rodney’s long-meter episode enlivens the mood, while Anderson’s solo uses space and motivic development to great advantage. Dial plays a beautiful solo with distinctive spacious lines before the trumpets’ fine unison statement of the theme. After the subdued coda, a French-speaking radio announcer cuts in to announce the titles of the last three pieces. “A Better Year” appears here for the only time in these recordings. It is a trio feature with Dial rhapsodic at the outset, growing more animated as the rhythm section enters. Anderson plays another fine solo with Hirshfield’s brushes in support. Dial plays more expansively in his next solo, while Hirshfield energizes the rhythm with his sticks. The horns return for a return appearance of “The Red Arrow”. This dependable flag-waver underwent few changes over the years, but here Sullivan plays his first solo with the full rhythm section, rather than the drums alone. Hirshfeld gets his solo opportunity following the trumpet chase. He plays a chorus of improvisation over the rhythm section and another two on his own. And is it humanly possible that the tempo is faster in this version than it was in earlier performances? (Yes, it is.) The final ten minutes of the broadcast contain a maddingly incomplete version of “Sprint”. We fade in on a drum solo and move into the main theme. Sullivan is less Coleman-like in tone but certainly plays far from any set harmonic patterns. For a while, two tempos appear to be happening at once—a slow one for Sullivan and Dial, and the speedy one for Anderson and Hirshfield. The same thing seems to happen with Rodney, except that the rest of the band falls into the medium swing feel. The “Free Jazz” quote is now played by both horns as an introduction to Dial, who improvises in a comfortable swing tempo with much more traditional ideas than at the Forum 19 months earlier. The radio announcer is dubbed in and the recording fades out at the end of a trio episode presumably new to this performance. So, a piece that clearly changes in every performance gets faded out by an insensitive engineer and ignorant producer. This recording was obviously edited to fit a one-hour time slot; couldn’t they have dropped the rhythm section feature and left “Sprint” uncut?

Smithsonian part 1

Our final two concert recordings were made by audience members. While there are obvious balance problems, the audio quality is surprisingly good. The first was recorded at the Smithsonian Institute on March 10, 1985, and it appears that most of the concert was captured. Joey Baron replaced Hirshfield, and he would continue as the band’s drummer until the group’s demise the following year. The first piece is “Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise”. Rodney’s muted trumpet and Sullivan’s flute split the theme, and the still-muted Rodney blows a fiery bop solo before Sullivan returns on alto sax, quoting “On a Clear Day” (shades of Berlin!) The two horns play the quote together a few times before Sullivan plays a passionate statement. “Clear Day” comes back at the end of his solo, and the horns toss the idea back and forth before yielding to Dial’s straight-ahead solo. On the first three pieces, the rhythm section is playing in straight bop style, with little of the melodic interplay heard in earlier concerts. As we will discover below, the timing of this concert had special significance for the bebop world. It is entirely possible that “Softly”—a favorite ballad for the boppers—was added at the last minute, and that the arrangement was created in the moment. The piece does not appear again in the quintet’s concerts. The next tune, “Groovin’ High” is also new to the repertoire, and it is another probable head arrangement. Rodney may have embraced contemporary jazz, but his solo here shows that he was a bopper to the core. Sullivan’s alto sax solo is more exploratory yet still falls within the bop framework. A collective improvisation leads to Baron’s Max Roach-inspired solo. One Gillespie composition deserves another, so the group moves directly into “Bebop”. The light-speed tempo sounds daunting, but not to Sullivan and Rodney who blast through the changes, quote “Things to Come” as before, but this time, throwing the spotlight to Dial. The pianist plays an impressive chorus before Baron takes another exciting solo. The horns pitch ideas over Anderson’s speed-walking bass, and the final theme is extended with emphatic reiterations of the song’s trademark motive.

As the band turns to its original compositions, Baron asserts his presence in the group. While some of these pieces might have been new to him, his drumming changes the character of these performances. “Monday’s Dance” is noticeably aggressive, with Baron’s accents propelling the trumpets during the exchanges. He nearly overwhelms the later dialogue between Dial and Anderson. In the final chorus, Baron pushes rather than glides, and that changes the overall groove. “Crescent City” fares better with the drummer encouraging Rodney and Sullivan along with a constant array of pops, hits, and bombs. After another fine Dial/Anderson episode, there is a sudden jump into Anderson’s bass solo, followed by an explosive drum solo and a spirited, foreshortened coda. Baron has many fine moments in this concert, including his beautiful samba patterns on the rhythm section feature, “Private Eye-Land” (the title—unmarked on the YouTube clip—was provided to me by composer Garry Dial).

Red and Ira return to the stage for “My Son, the Minstrel” in an arrangement essentially unchanged from the commercial recording. The exchanges go on for an extra minute, and the song’s gimmick starts to wear off. The “Greensleeves”/“Giant Steps” medley loses the dramatic bass/drum interruptions of the theme statement. After Red’s beautifully constructed solo, Ira builds his soprano solo on the Richard Rodgers show tune, “We Kiss in a Shadow”. Baron takes over with a huge crescendo and then plays the first part of his statement over a rhythm section vamp. When the rhythm section drops out, he demonstrates his mastery of the drum kit using the tuned toms and various cymbals to great effect. The band returns with a sample of the “Giant Steps” theme before Sullivan rolls into a complex improvisation. Rodney builds his solo on a repeated motive. The rhythm switches to 3/4 time when the theme returns (which begs the question of what actually happened in that spot at the Montreal concert).

Rodney introduces a new Garry Dial piece, “Never Enough” dedicated to the memory of Charlie Parker. This concert took place two days shy of the 30th anniversary of Parker’s death, and that explains the high concentration of bebop on this concert. Dial’s elegy is intoned by the soprano sax, and Sullivan makes his horn moan and cry with memories of the fallen icon. Dial takes over for a stunning solo chorus, played with the sensitivity of a concert pianist. Sullivan returns, and the duo collaborates for a dramatic finale, complete with great crescendos and an understated coda. “Speak Like a Child” is an obvious follow-up, and despite the change to alto flute, Sullivan appears to follow in the same manner as the previous piece. However, there is a sudden and awkward splice and we move forward to Rodney’s duet with Sullivan. The long-meter episode never really happens; instead, the rhythm intimates a medium walking tempo for the flugelhorn. Anderson’s solo is accompanied by a combination of cymbal and clavé (Sullivan likely playing the Latin percussion). Again, Dial’s solo brings everything down to a pianissimo and then crescendos back for the trumpet’s unison theme. Rodney’s trumpet makes a pointed statement, punctuated by Baron before Sullivan switches back to flute for the final phrase. Next, Ira and Red joke with the audience about putting “The Red Arrow” in the Smithsonian archive after the concert, then they give the old flag-waver a spirited performance. The trumpet solos and exchanges are accentuated by Baron’s rimshots, and then Dial bops through two choruses with new punctuations by the horns. Baron launches his final solo with a rattling intro into…silence! When he has the audience’s attention, he dazzles with a finely-modulated solo that excites and inspires at the same time. “Amazing Grace” closes the concert. As on the commercial recording, Sullivan’s soprano dominates the piece, but Rodney and Anderson contribute to the ongoing drone. Dial evokes a down-home church pianist before Ira returns on flute to reiterate the melody.

[One further broadcast recording belongs in this space. In April 1985, the band played at the 4 Queens Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. One set was recorded for broadcast on NPR. The master tapes now reside at the University of Las Vegas, but the Rodney/Sullivan tapes are in very poor condition, and the copy I received was virtually unlistenable. Trumpeter Brad Goode, who knew and worked with both Ira and Red, is presently searching for his cassette copy of that broadcast. If he finds it, and the copy is of acceptable quality, a discussion of it will appear here.]

In June 1985, Rodney and Sullivan appeared at the Jazz Showcase in Chicago. The only member of the regular rhythm section to make the trip was Joey Baron. The replacements for Dial and Anderson were Gerard D’Angelo and Michael Formanek respectively, both fairly new to the NYC jazz scene at the time, but each well-qualified to cover the parts. The opener is “Speak Like a Child”, and the music is accompanied by a sotto voce dialogue as the amateur engineer tries to explain jazz improvisation to his girlfriend! Onstage, the arrangement follows the established pattern: rubato alto flute/piano duet followed by solos on alto flute and flugelhorn (the latter at walking tempo). The order of piano and bass solos are reversed which means that the big crescendo into the trumpet unison theme is missing, thus robbing the piece of its natural climax. Rodney’s punctuated statements return in the coda, and Sullivan’s final phrase is expanded over the final vamp. “Recorda-Me”, recorded at the initial Vanguard sessions—and still not released by 1985! —is the next selection. Rodney and Sullivan both play trumpets on this track, and it feels more like a jam session than the performance of a polished arrangement. Both horn men are ready for another trumpet chase, and Baron’s active drumming clearly inspires the duet to greater heights. Tadd Dameron’s “If You Could See Me Now” starts as a rubato ballad feature for trumpet and flugelhorn, but after the theme, the tempo moves into a medium groove, and Red and Ira play expressive solos, inspired by the swinging rhythm section and fresh setting. The coda dovetails into “The Red Arrow” and we’re off to the races again! The inspiration was running high that night, and both Red and Ira have loads of reserve energy. Baron’s drum solo with mallets and brushes uses silence to quiet the crowd. However, an abrupt jump in the recording moves us to the out chorus. Sullivan brings out his alto sax for a reprise of his lovely treatment of “I Got It Bad”. This version moves further from the melody than the Vanguard recording, and Sullivan’s yearning tone and heartfelt improvisation sings of pain and lost loves. Sullivan switches to soprano for the “Greensleeves”/“Giant Steps” medley. Rodney’s lyricism seemed to grow deeper with each version of this piece, and the brief duets on either side of his solo are a pleasant touch. Sullivan’s solo is loaded with intensity and drive. Although Sullivan does not duplicate the blinding speed of Coltrane on soprano, Baron takes the opportunity to show off his Elvin Jones influence. The “We Kiss in a Shadow” quote returns before Baron takes the solo spotlight. Again, the cymbals play a primary role in his invention. “Giant Steps” has brief flugel and soprano solos before a speedy coda. The final “Amazing Grace” finds Sullivan’s soprano shifting registers like a bagpipe before the stretched-out theme statement by soprano and flugel. We don’t know what happened after that as the tape suddenly ends.

We have one further performance to explore. It is a highly edited TV program with clips of the regular quintet performing in the Leverkusen jazz club in West Germany in October 1985. The embedded clip below starts with a partial version of “Spirit” and follows with J.J. Johnson’s blues “Wee Dot”. “Sprint” opens with a Cecil Taylor-inspired improvisation by Dial, and moves to the Coleman “Free Jazz” quote segment. Anderson and Baron engage in an intense free jazz conversation, then the tempo speeds up and the horns reprise the main melody. “Wee Dot” is much more fun. Here, at last, is an opportunity to watch Rodney and Sullivan lock horns. After the initial choruses and exchanges, Sullivan indicates a chorus with Baron alone. Rodney, suddenly looking like a kid on a dare, decides to top him with a muted chorus with Anderson. Even after five years together, Red and Ira were still having a great time on stage.

Yet, a year later, it was all over. The combination of Ira’s fatigue with the road and his preaching from the stage led to the end of the group. Rodney led bands with Dick Oatts and Chris Potter in the next few years, and he even tried to mix bebop with rap! He was a technical advisor for Clint Eastwood’s biopic of Charlie Parker, “Bird”, both coaching the young actor who was to play him and performing on the movie’s soundtrack. Rodney succumbed to lung cancer in 1994. Sullivan went back to Florida, made yearly visits back to Chicago and the Jazz Showcase, and recorded an impressive array of albums up until his passing in 2020. Dial taught and played in New York until the outbreak of COVID-19, when he moved to a vacation home in the Virgin Islands. He still comes up to New York for occasional gigs. Anderson is a highly regarded leader and composer in New York. For many years, he has anchored the rhythm section of the Maria Schneider Orchestra. Baron now lives in Germany, but he is in constant demand as a drummer for groups large and small.

While dissolving a long-standing quintet was difficult, both Red and Ira held fond memories of the group. Dial and Sullivan spoke many times over the years, with Sullivan whistling tunes, and recalling various performances and after-hours adventures of the group. Rodney told Ben Sidran, Ira and I seem to play very well together. We don’t know why. We’re very friendly, but we’ve never hung out together…We love each other dearly. We sort of had a feeling for each other, and none of us could understand it. We knew when [the other man] would breathe. Ira always makes you play better. He has such great energy. Rodney, who probably made greater musical leaps than anyone in this quintet, certainly knew the inspiration for his growth.

Dedicated to the memory of Stan Baran (1964-2014).

The history of the Red Rodney/Ira Sullivan quintet is necessarily incomplete, with significant gaps between recordings. Anyone holding concert or broadcasts of this group not already discussed are encouraged to reach out to Thomas Cunniffe at tomsjazz@msn.com so that these performances may be considered in revised versions of this article.

Thanks to Brad Goode, Paul Baker, Garry Dial, Jay Alexander, Joey Baron, Jack Wilkins, Jack Walrath, Susan Tobocman, Steve LaSpina & Jim Eigo.

Cover photo by Brad Goode.

The audio and video recordings embedded in this article are presented for educational and illustrative purposes. Jazz History Online neither owns nor controls the rights to these recordings. All rights belong to the original copyright holders.

.