From the early fifties until his death in 1995, Marty Paich was one of the top arrangers for jazz and pop singers. Paichwas especially adept at showcasing the best qualities of a vocalist. Like many arrangers, Paich could work independently, developing charts from what he knew of the singer’s range and abilities. But Paich enjoyed collaborating with his featured artists, incorporating ideas that the vocalist had been willing to try, but had not successfully implemented. There is no better example of such collaboration than Paich’s teaming with Mel Tormé in their series of albums featuring the dek-tette.

and abilities. But Paich enjoyed collaborating with his featured artists, incorporating ideas that the vocalist had been willing to try, but had not successfully implemented. There is no better example of such collaboration than Paich’s teaming with Mel Tormé in their series of albums featuring the dek-tette.

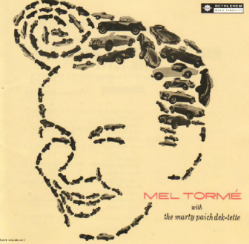

The very idea of the dek-tette was Tormé’s. Tormé had been introduced to Paich’s work through his cool jazz-influenced small group charts, and in 1955, when Tormé changed labels from Decca to Bethlehem, he specifically requested to work with Paich. Both Tormé and Paich were fans of the Gerry Mulligan Tentette and Tormé wanted to use that style as a backup for a vocal album. For the horns, Paich retained the Mulligan group’s coupling of brass quintet (2 trumpets, trombone, french horn and tuba) and saxophone trio, but opted for alto, tenor and baritone sax rather than Mulligan’s alto and 2 baritones. Further, at Tormé’s urging, Paich omitted the piano from the rhythm section, allowing the singer to “stroll” with only bass and drums in accompaniment. Of course, it was Tormé’s remarkable sense of pitch that allowed him that luxury. Yet Tormé was not satisfied with just a new backdrop. For their first album, “Mel Tormé & The Marty Paich Dek-tette,” the vocalist and arranger specifically looked for songs that had not been widely heard, and whether by coincidence or design, not yet recorded by Frank Sinatra (Of course, one of the tunes on the album, “The Lady Is A Tramp”, eventually became a Sinatra vehicle,  but Sinatra didn’t record it until October 1956, 10 months after this Tormé/Paich version). Tormé was also interested in showcasing his scat singing, his compositional gifts, his ability to blend with horns, and his uncanny talent for performing unassisted modulations.

but Sinatra didn’t record it until October 1956, 10 months after this Tormé/Paich version). Tormé was also interested in showcasing his scat singing, his compositional gifts, his ability to blend with horns, and his uncanny talent for performing unassisted modulations.

From the first notes on the first track, the listener can tell that this is no ordinary vocal album. “Lulu’s Back in Town” opens with Al Pollan’s sprightly tuba performing a syncopated pedal point over the swinging rhythm provided by bassist Red Mitchell and drummer Mel Lewis. Then Tormé enters, not with Harry Warren‘s original melody and Al Dubin‘s lyric, but with an original verse. The horns, which entered with Tormé, back him up with soft sustained chords which peak with Tormé on the line, but oo-oo, Lulu giving us our first taste of the dek-tette’s marvelous ensemble sound. Next, Tormé begins to sing the original tune, not with the usual herky-jerky dotted-eight/sixteenth note patterns, but with smoothed-out quarter/eighth triplets, transforming Lulu from an uptight square to a swingin’ chick! The horns return on the fifth bar of the tune, on the line, ’cause tonight I gotta look my best. The underlined words are accented by the horns with a long quarter/staccato eighth note pattern. On those words, Tormé matches the tonal inflections produced by lead trumpeter Pete Candoli, which basically turns Tormé into the eleventh member of the band, and—with Candoli—the co-leader of the ensemble! After solos by alto saxophonist Bud Shank and valve trombonist Bob Enevoldsen, Tormé re-enters with a reprise of the verse, and then the horns mimic his last phrase up a half-step to modulate into the last chorus. The first sixteen bars of this chorus is a big-band styled shout chorus, with Tormé clearly the lead voice in the band, and the horns punching identical rhythmic figures in the background. Then to begin the final eight bars, Paich and Tormé find the perfect medium between the shout chorus material and the original tune: a shout figure closely based on the melody, which gains momentum by eliminating one note and adding a strong syncopation to the note that follows. In the seventh bar, Tormé melds into the coda, which repeats a variation of the final line in two successive keys, followed by a new shout figure which is cut short with Tormé’s final held note. The video clip below finds Tormé singing the Paich arrangement on a 1967 television show, accompanied by members of the Stan Kenton orchestra.

“Lulu” was just the beginning! The remainder of the first dek-tette album covered a wide variety of jazz styles: the Latin rhythms of “The Carioca,” the big-band style of “Fascinating Rhythm,” the dramatic ballad lines of “When The Sun Comes Out,” and the laid-back cool jazz of “Lullabye Of Birdland” (the latter featuring an extended scat solo by Tormé). Also included was the very funny Rodgers and Hart classic, “I Like to Recognize the Tune” and the starkly dramatic Ellington re-creation of “The Blues” from “Black, Brown and Beige“. The obvious reason for such a broad spectrum was that Tormé and Paich wanted to show all the various styles that the dek-tette could embrace. At the time, the dek-tette was not intended to survive past the original LP. After the album was completed, Tormé went back to his nightclub engagements and Paich toured England with Dorothy Dandridge. The album was released while Paich was away, and when he retrieved his phone messages, he had several requests from other singers to use the dek-tette on their next albums. In a “Down Beat” interview from 1956, Paich said he would have to re-form the dek-tette for future recordings.

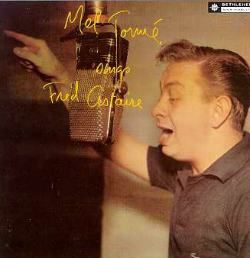

Now that its future seemed guaranteed for at least a few albums, there was no need to display every aspect of the dek-tette’s sound on every album. Now Paich could focus on one style of writing for each LP, thus subtly unifying the sound of each successive album. Also, several of the subsequent dek-tette LPs were “concept albums”, where all of the music was related by a common conceptual theme. In 1956, this was a fairly new idea, but throughout the recording industry, it was quickly adopted as a potent creative outlet and a brilliant marketing idea. Thus, the musicians were quite careful not to include any songs that fell out of the album’s concept, and the marketing department was sure to advertise the album’s concept in the LP title. These unification tactics were certainly apparent on the dek-tette’s next album, also for Bethlehem, “Mel Tormé Sings Fred Astaire”. The songs, which had all been introduced in Astaire’s films, were not only top-notch, and more familiar. Tormé is in magnificent voice, contributing a cappella intros to “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” and “A Fine Romance,” blending into the horn section on “A Foggy Day” and “Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” and forcefully swinging through the up-tempo “Way You Look Tonight.”

Paich’s arrangements, featuring long stretches of block scoring, are less interesting from a strictly aural standpoint, but the album opener, “Nice Work If You Can Get It” features amazing formal play by Paich, and a remarkable performance by Tormé. The arrangement starts conventionally enough: Tormé sings the first chorus accompanied by the horns, then there is a reprise of the introductio n, which is followed by a half-chorus of exchanges with the ensemble taking the first six bars of each stanza and Tormé capping off the phrase with the title line. Then things get interesting: Instead of going to the bridge, Tormé segues to the verse, then back to the beginning of the original tune. At the second eight, Tormé pulls off a perfect unassisted half-step modulation, and four bars later we are suddenly in the coda. Tormé sings the title line, is interrupted by the horns, repeats the line in a different key, continues with and if you get it, is again interrupted, and then finishes the line, Won’t you tell me how? as the arrangement concludes with another echo of the introduction.

n, which is followed by a half-chorus of exchanges with the ensemble taking the first six bars of each stanza and Tormé capping off the phrase with the title line. Then things get interesting: Instead of going to the bridge, Tormé segues to the verse, then back to the beginning of the original tune. At the second eight, Tormé pulls off a perfect unassisted half-step modulation, and four bars later we are suddenly in the coda. Tormé sings the title line, is interrupted by the horns, repeats the line in a different key, continues with and if you get it, is again interrupted, and then finishes the line, Won’t you tell me how? as the arrangement concludes with another echo of the introduction.

Both Paich and Tormé were justifiably proud of this album. For Tormé, it was a lovingly conceived tribute to his favorite singer (While preparing for the album, Tormé phoned Astaire to ask about specific tunes and tempos. He was astounded to find that Astaire not only degraded his own singing, but was surprised that anyone would consider doing an LP in tribute!) Paich, in the meantime, saw a considerable future with the dek-tette, and so, took more care in polishing the ensemble playing of the group. The dek-tette’s ranks were filled with some of California’s finest jazz musicians (many of whom performed on dek-tette recordings for another decade) but beginning on the Astaire sessions, Paich worked hard to ensure that the group phrased together, and closely followed the dynamics he had included in the score. The results are clearly found in the recording, especially in the beautifully executed group phrasing on “Something’s Gotta Give.”

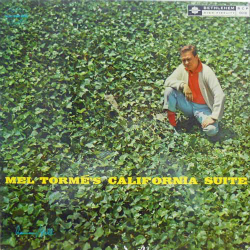

The dek-tette’s third album, recorded for Bethlehem in March 1957, was a remake of Tormé’s “California Suite”. Originally written in 1949, California Suite was Tormé’s answer to Gordon Jenkins‘ New York City tribute, “Manhattan Tower” (recorded for Decca in 1946). It is essentially a song suite woven together by vocal verses and instrumental interludes. The songs include tributes to many of California’s cities, including San Diego, San Francisco, La Jolla and Hollywood, and while there is a great deal of cheerleading for the Golden State, there are also complimentary sections on Coney Island and Atlantic City. There are two featured voices: Tormé, a “California rooter” and “The Easterner”, a New Yorker with lots of attitude and a very pronounced accent (portrayed on the original Capitol recording by Peggy Lee). In contrast to the real-life verbal battles between New Yorkers and Californians, Tormé’s piece never really provokes any heated discussions between the two protagonists. Instead, Tormé’s character recognizes the splendor of the East Coast, and then simply points out that California has its own splendor. In addition to Tormé and Lee, the original recording featured Mel’s vocal group, The Mel-Tones, with a large orchestra and chorus. Although the performances are exemplary, the arrangements (credited to eight writers, including Tormé) have not aged well. The orchestrations are straight out of the Hollywood mill: big and flashy, with lots of harp glissandi and overblown endings. As for the Mel-Tones’ sections, Tormé’s voicings sound like they were lifted straight out of arrangements for Tommy Dorsey‘s Pied Pipers or Glenn Miller‘s Modernaires. If this style was not passé by 1949, it certainly became so within a few years of the recording. It was probably the arrangements that led Tormé to remake “California Suite” in 1957.

In the 1957 version, the Mel-Tones are gone, and the orchestra is the dek-tette, augmented by a small string section. The chorus is smaller, and some of the choral passages are transformed into Tormé solos. Tormé and Paich were the only musicians listed on the album jacket, and the full per sonnel has only been recently identified through a combination of recording contracts and memories of those present. However, we may never know the identity of the young lady who portrays “the Easterner”. According to the album’s choral director and contractor, Randy Van Horne, “the Easterner” was played by a girlfriend of the producer, and that her acting and singing abilities were not her most obvious assets. In fact, she was unable to properly execute her final line, California’s everything you told me/Hey, you sold me! and drummer Al Stoller’s screeching of the line in falsetto was eventually dubbed on to the master tape! Paich’s arrangement follows the Capitol version closely, eschews the Hollywood flash, and implements the dek-tette in the jazz settings. The dek-tette’s ensemble work is especially noteworthy: the punch figures are tightly executed, yet the laid-back West Coast swing is never sacrificed. The string writing is refreshingly understated, especially in the Atlantic City waltz and in the backgrounds to “Poor Little Extra Girl”. The opening of the second side features a section with three tempi occurring simultaneously, and a little later in the same movement, there is a sultry alto sax solo by Ronnie Lang, which perfectly evokes the sound of film noir scores. Tormé, obviously relishing the chance to perform his own magnum opus, sings splendidly throughout, acting as lead voice for the chorus in several sections, and contributing exemplary solo work elsewhere. His reading of “Poor Little Extra Girl” was one of his finest ballads up to that time, and his high-spirited vocals in the up-tempo sections helped overcome the weaknesses of the work. And who else but Tormé could put over a line like La Jolla won’t annoy ya?

sonnel has only been recently identified through a combination of recording contracts and memories of those present. However, we may never know the identity of the young lady who portrays “the Easterner”. According to the album’s choral director and contractor, Randy Van Horne, “the Easterner” was played by a girlfriend of the producer, and that her acting and singing abilities were not her most obvious assets. In fact, she was unable to properly execute her final line, California’s everything you told me/Hey, you sold me! and drummer Al Stoller’s screeching of the line in falsetto was eventually dubbed on to the master tape! Paich’s arrangement follows the Capitol version closely, eschews the Hollywood flash, and implements the dek-tette in the jazz settings. The dek-tette’s ensemble work is especially noteworthy: the punch figures are tightly executed, yet the laid-back West Coast swing is never sacrificed. The string writing is refreshingly understated, especially in the Atlantic City waltz and in the backgrounds to “Poor Little Extra Girl”. The opening of the second side features a section with three tempi occurring simultaneously, and a little later in the same movement, there is a sultry alto sax solo by Ronnie Lang, which perfectly evokes the sound of film noir scores. Tormé, obviously relishing the chance to perform his own magnum opus, sings splendidly throughout, acting as lead voice for the chorus in several sections, and contributing exemplary solo work elsewhere. His reading of “Poor Little Extra Girl” was one of his finest ballads up to that time, and his high-spirited vocals in the up-tempo sections helped overcome the weaknesses of the work. And who else but Tormé could put over a line like La Jolla won’t annoy ya?

After “California Suite”, Paich recorded several dek-tette albums with other singers, including Jeri Southern, The Hi-Lo’s and Ella Fitzgerald. Tormé recorded one LP for the Tops label, before moving to Verve Records. Both the Tops and the first Verve LP were arranged and conducted by Paich, but the dek-tette was not used on either album (The Tops lists the dek-tette as the backing group, but neither the sound nor the instrumentation matches the classic dek-tette style.) It would be nearly three years before Tormé would record again with the Paich dek-tette, but when they were reunited, they created a classic for the ages: “Mel Tormé Swings Shubert Alley”. On this album, Tormé and Paich explore songs from the “book” musicals. These Broadway shows, starting with 1943’s “Oklahoma!,” integrated story, music and dance to a higher degree than ever before. Fittingly, Shubert Alley is also highly integrated: song quotes, formerly used in Paich’s dek-tette scores, now became predominant parts of each arrangement. In addition, many of the tracks end with short, bluesy tags, which also subtly tie the 12 arrangements together. Many of the concepts used in earlier dek-tette LPs are expanded or re-examined. The tuba takes on new predominance in the part-writing (and is beautifully captured in the excellent recording mix). In a “Down Beat” interview, Tormé told Leonard Feather, I don’t think I can sing better than I did on ‘Shubert Alley’ and I don’t think I could get better backing than I got from Marty Paich. Everyone involved in this recording was operating at peak level, and the album was an undisputed mas terpiece. Since “Shubert Alley” works so well as a unified album, it is almost unfair to single out individual tracks for praise. Suffice to say that every track on this album deserves (and withstands) close scrutiny; however, here are a few of the album’s many highlights.

terpiece. Since “Shubert Alley” works so well as a unified album, it is almost unfair to single out individual tracks for praise. Suffice to say that every track on this album deserves (and withstands) close scrutiny; however, here are a few of the album’s many highlights.

The opening track, “Too Close For Comfort”, effectively reprises and expands on several of the ideas presented on the first dek-tette album. Tormé opens the album unaccompanied with original music: Be wise…Be fair…Be sure…Be there…Behave…Beware with the dek-tette echoing each phrase. Tormé begins the tune, accompanied by punch figures in the saxophones, with the brass joining in for the last bar, followed by a 3-bar extension. In the next eight, all the horns accompany Tormé, and in the bridge, Tormé is left with just bass and drums, with the horns contributing ensemble figures between Tormé’s phrases. For the next eight, the saxes return with the same figure as before, and on the underlined words in the song’s final section, One thing leads to another/Too late to run for cover/She’s much too close for comfort, Tormé again plays “lead horn” in the ensemble. Tormé doesn’t actually finish this chorus; after the lines above, the song cadences on the word “now”; then Tormé and alto saxophonist Art Pepper insert the first of the album’s song quotes, Charlie Parker‘s “The Steeplechase.” The quote doubles as a transition, and Pepper launches his solo, with background figures and a brief interruption by the dek-tette. When Tormé returns, it is with a shortened version of the introduction. With a short ensemble passage, we encounter another shout chorus. As in “Lulu’s Back in Town”, Tormé matches his phrasing to the horns. However, the concept of this shout chorus is much more complex than in “Lulu”. To begin with, the trumpets do not actually play the shout figures with Tormé, but contribute a muted figure between the shout phrases. Also, the shout figures do not begin on the first bar of the phrase. Tormé sings Put on your old thinkin’ cap, boy/’cause if you don’t look out/she…will have you up that old tree with the horns coming in on the underlined words. The trumpets turn up again for ensemble figures at the end of each eight-bar section, but at these points, they play unmuted. The 16 measures of shout chorus is only a preamble to the stunning bridge, which builds and builds with Tormé’s impassioned Too close…too close…much too close over the dek-tette’s powerfully swinging background. The bridge reaches its peak with two stop-time scat passages by Tormé. Then it’s back to the tune, appropriately with just bass and drums in accompaniment. When the horns return, there is more of the shout chorus style, but here, as in “Lulu,” it is the original tune that is now receiving the shout chorus treatment. The section in question, One thing leads to another/Too late to run for cover/She’s much too close for comfort now is repeated twice as a quasi-tag, with different backgrounds used each time and with bass fills by Joe Mondragon inserted between each repetition. Then the introductory material returns, capped with Tormé’s She’s too close, too close for comfort now set to one of jazz’s oldest cadential formulas, but saved from triteness by Paich’s setting of it for voice and tuba. There is a final chord, and a brief improvised tag by Pepper.

Closing the first side is one of the most difficult arrangements ever conceived for a vocalist, “Just In Time”. The tune is quite simple, based on a three-note motive, with the middle note a minor second below its two neighbors. The lyric speaks of the singer being in imminent danger before love (and his new lover) came “Just in Time”. Paich’s arrangement matches that sentiment exactly by placing Tormé in treacherous areas where, if not for his superior musicianship, the singer could wander off-pitch or lose the melody altogether. That Tormé pulls it off is a testament to his standing as one of the finest singers in jazz. The arrangement opens with only Mondragon’s walking bass. Then Tormé and Lewis enter, and the three men comprise the instrumentation for the entire first chorus. This is the longest sequence in the entire dek-tette discography where a vocalist is accompanied by just bass and drums. When the horns finally come in, it is not with a background to “Just in Time”, but an extended quote from “Who’s Sorry Now”. With eight horns surrounding him playing a completely different tune (with only similar chord changes) Tormé continues “Just in Time” for 16 bars, never faltering in pitch or melodic accuracy. The quote is quite noteworthy in its own right. In an interview, Tormé told me that he came up with all of the song quotes on “Shubert Alley”. However, it is clear that it was Paich’s artistry that made them succeed. The “Who’s Sorry Now” quote continues for 12 full bars, and to get out of it, Paich takes its last note, extends it over the bar line, and seamlessly makes it the first note of an original background figure to fill the remaining bars of the phrase. It is a masterful technique, and one easily missed if the listener is focusing on Tormé and not the band. The ensemble bridge that follows peaks the intensity and volume of the arrangement. Then suddenly, it is Tormé with bass and drums again. He sings with them until the line, lonely life, that lovely day, which is sung nine times, in three groups of three. The first time is with bass and drums, but each successive group adds instruments and volume. The final repeat is extended with Tormé’s original day you changed my life, that lovely day and punch figures from the ensemble which crescendo throughout. When Tormé holds the word “day,” there is a closing ensemble tag which again challenges Tormé, since there are strong dissonances between Tormé’s held note and those played by Red Callender’s tuba. The arrangement sounds as if it’s finished here, but after a slight pause, there is a short sax soli, and an improvised tag by trumpeter Stu Williamson.

Paich and Tormé take quite a few liberties with the formal scheme of Cole Porter‘s “Too Darn Hot”. Originally in an odd AAABC form, but usually adapted to an AABA form by singers, the “Shubert Alley” version goes in the other direction by adding another A section, and delaying the C until the very end of the performance. After the introduction, which features a scorching bop line for alto and trumpet, Tormé sings the first A section. There is an extension, and a solo break for trombonist Frank Rosolino, who continues soloing in the next A section, while Tormé lays out. (Suffice to say, the interruption of the vocalist during the first theme statement is very unusual!) After Rosolino finishes, Tormé modulates up a step and sings the next A section. The extension, break and solo pattern is repeated, only this time Art Pepper is featured. After Tormé’s bridge, there is an ensemble passage before Tormé returns with yet another A section. Although the extension and break return (with the break by Mel Lewis), there is no solo. Rather, we move directly to the bridge, where Tormé pulls off an amazing set of modulations. On the words, According to the Kinsey Report/Every average man you know, Tormé modulates up a half-step on the words “Kinsey” and “average,” then back down by half-steps on the words “man” and “know.” It is the musical equivalent of a tap dancer going up one side of a stage staircase and then down the other side. The bridge now leads to the only appearance of the C section, which is extended into the brief coda. Tormé also sang this chart on the 1967 television show, but before starting the arrangement, he tells the audience about the dek-tette, and acknowledges Paich’s contribution.

Tormé and Paich teamed up again in 1988 for “Reunion“, a studio album recorded for Concord Jazz. By this time, Tormé had established himself as the preeminent jazz vocalist of his era and Paich had expanded into pop music and film scores. The dek-tette, which had last recorded for an Ella Fitzgerald LP in 1966, now featured a very different personnel. Further, Paich added both piano and synthesizers to the instrumentation. “Reunion” displayed an expanded repertoire as well: alongside remakes of “The Blues”, “Too Close for Comfort” and “The Carioca” were tunes by Donald Fagen, Chick Corea and Antonio Carlos Jobim. Also included were song m edleys where a portion of one song became the verse for another. This had become one of Tormé’s favorite devices, and clearly a development of the quotes used on “Shubert Alley”. Tormé’s scat singing was a prominent part of these arrangements, especially on “Sweet Georgia Brown” where, at a blistering tempo, Tormé fires off scat exchanges with alto saxophonist Gary Foster, trumpeter Jack Sheldon and drummer Jeff Hamilton. The arrangement is filled with quotes, opening with the “Lulu” verse, incorporating an entire chorus of Gerry Mulligan’s “Roundhouse” and using “Rose of the Rio Grande” as a solo backdrop.

edleys where a portion of one song became the verse for another. This had become one of Tormé’s favorite devices, and clearly a development of the quotes used on “Shubert Alley”. Tormé’s scat singing was a prominent part of these arrangements, especially on “Sweet Georgia Brown” where, at a blistering tempo, Tormé fires off scat exchanges with alto saxophonist Gary Foster, trumpeter Jack Sheldon and drummer Jeff Hamilton. The arrangement is filled with quotes, opening with the “Lulu” verse, incorporating an entire chorus of Gerry Mulligan’s “Roundhouse” and using “Rose of the Rio Grande” as a solo backdrop.

The album’s highlight is a medley which takes “The Trolley Song”, a song of first love, and moves the relationship into matrimony with “Get Me to the Church on Time.” The opening verse of “Trolley” modulates from D-flat to D at its halfway point. There is another modulation (to E-flat) at the beginning of the chorus, and that’s when this trolley moves! At perhaps the fastest tempo on any dek-tette record, Tormé and the dek-tette speed through two choruses, including a half-chorus of lightning-quick improvised exchanges with Tormé, Foster, Sheldon and Hamilton. The second chorus is never actually completed: at the words, When the universe reels, Paich inserts a transition and Tormé goes into an original verse, We met on the trolley/and we fell in love./I’ll never fail her/I’ll never fault her/My gal & I are on the way to the altar. There is another key change (back to D-flat) to introduce “Church”. Before the dek-tette joins in, there is a cute eight-bar passage where Tormé’s primary backing is the tuba in a mocking “whump, whump” accompaniment that emulates the English music-hall style of the original tune. Tormé sings one chorus of “Church”, then, with an unassisted modulation, moves back to E-flat for a final half-chorus of “Trolley”. But Paich has saved his best joke for last: at the closing lyric, to the end of the line, Paich uses the dek-tette to simulate the trolley’s slowing and stopping. There is a long descending glissando to two eighth notes–a motive used in several previous dek-tette charts–but here, the second note is held, while Hamilton’s brushes simulate the gradual slowing of the steam engine. While trolley cars don’t actually have steam engines, it’s still a great effect!

In December 1989, Tormé, Paich and the dek-tette traveled to Tokyo to perform at the Fujitsu-Concord Jazz Festival. Their concert was videotaped for Japanese television and released by Concord Jazz as the dek-tette’s final album, “In Concert Tokyo”. There’s no new material for the dek-tette here but there are superior versions of earlier triumphs. The “Bossa Nova Potpourri” medley, featuring interweaving renditions of “One Note Samba,” “How Insensitive” and “The Gift”, features an extended tag with Tormé scatting over the surging rhythm section fueled by John von Ohlen‘s drums. The video clip is from the Japanese TV broadcast:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRQvl3bAZHg

Tormé replaces von Ohlen at the drums for a powerful “Cottontail” (previously recorded on Paich’s instrumental LP, “I Get a Boot out Of You”) which evolves into a recreation of the Benny Goodman/Gene Krupa duet from “Sing, Sing, Sing“. Of the remakes from the original dek-tette albums, only “On The Street Where You Live” and “The Carioca” are completely successful; on “Just In Time” pianist Allen Farnham compromises the mood of imminent danger by comping throughout the first chorus, and on “When The Sun Comes Out” a trombone solo is substituted for the absent french horn of original dek-tette member Vince De Rosa, losing the creamy sound that only De Rosa seemed capable of producing.

Before his passing, Marty Paich told me that he wanted to do further recordings with the dek-tette, including collaborations with young, upcoming singers. Unfortunately, those projects never happened. Now that Tormé has left us too, we’ll never hear his up-to-date interpretations of the dek-tette classics. While a number of singers (including Dennis Hastings, Jeff Hedberg, and Tormé’s son, Steve March Tormé) have recorded and performed transcriptions of Paich’s original dek-tette scores, no one seems to have taken the next step to write new arrangements in the dek-tette style. (The dek-tette’s final pianist, Allen Farnham did create a few small band charts for singer Susannah McCorkle, but Farnham did not write any small band followups for other singers after McCorkle’s suicide in 2001). The concept of the dek-tette may have died with Tormé, Paich, and Gerry Mulligan, but the music still sounds fresh today. If you don’t believe that, just put on “Shubert Alley” again.

©1999-2016 Thomas Cunniffe.