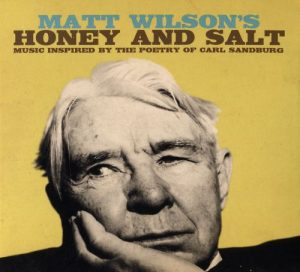

In addition to being brilliant poets, Emily Dickinson and Carl Sandburg shared a deep appreciation for music. Dickinson took to the piano as a toddler, and eventually learned how to improvise in the style of the great classical composers. At least one scholar has found that Dickinson’s poems use the identical meter and structure of 19th century hymns and popular songs. Sandburg was a dedicated jazz fan and a noteworthy performer of folk music. The love of spontaneous invention informed the poetry of both Dickinson and Sandburg, as each found idiosyncratic ways to break existing molds and challenge readers. Dickinson used unusual capitalization and a complex series of hyphens and dashes, which are still being deciphered today; Sandburg created unique written constructions that resembled—but were not universally defined as—free verse. The latest albums from two of today’s most progressive jazz musicians celebrate this unique pair of iconoclastic poets: Jane Ira Bloom’s “Wild Lines: Improvising Emily Dickinson” (Outline 143) and Matt Wilson’s “Honey and Salt: Music Inspired by the Poetry of Carl Sandburg” (Palmetto 2184).

In terms of the overall structure, Bloom and Wilson take diametrically opposite approaches. Wilson lets Sandburg’s words unify the suite, while Bloom uses her music as the constant element. Bloom’s album is a double-disc set. The first disc contains the music alone. Without knowledge of the album title, an astute listener would probably recognize that the music was written by the same person, but might miss the connection to Dickinson (In fact, several of these compositions appeared on Bloom’s previous album, “Early Americans” and as my review shows, the music brought entirely different images to my mind—and going back to those earlier recordings, I stand by my assertions!). However on the second disc, with Deborah Rush’s impeccable poetry readings included alongside the music, the relationship of the two elements comes into focus. Wilson uses a wide variety of speakers for 10 of his album’s 18 tracks, and he matches the characteristics of the voices to his highly diverse musical settings. For example, Jack Black’s gruff-voiced recitation of “Snatch of Sliphorn Jazz” accompanies a wild free jazz duet by saxophonist Jeff Lederer and drummer Wilson, while Carla Bley’s reading of “To Know Silence Perfectly” precedes and follows a thorough-composed canon where the individual entrances are spontaneously determined by the musicians. To fill out the suite, Wilson has set several Sandburg poems to his own music, and the dramatic (and witty) contrasts between the settings hold the listener’s attention. Country, gospel, funk, marches and a wealth of jazz styles appear side-by-side on Wilson’s album, and his amazing musicians (cornetist Ron Miles, guitarist and vocalist Dawn Thomson, Lederer—doubling on several reed instruments and harmonium—and bassist Martin Wind) embrace each style with confidence.

In terms of the overall structure, Bloom and Wilson take diametrically opposite approaches. Wilson lets Sandburg’s words unify the suite, while Bloom uses her music as the constant element. Bloom’s album is a double-disc set. The first disc contains the music alone. Without knowledge of the album title, an astute listener would probably recognize that the music was written by the same person, but might miss the connection to Dickinson (In fact, several of these compositions appeared on Bloom’s previous album, “Early Americans” and as my review shows, the music brought entirely different images to my mind—and going back to those earlier recordings, I stand by my assertions!). However on the second disc, with Deborah Rush’s impeccable poetry readings included alongside the music, the relationship of the two elements comes into focus. Wilson uses a wide variety of speakers for 10 of his album’s 18 tracks, and he matches the characteristics of the voices to his highly diverse musical settings. For example, Jack Black’s gruff-voiced recitation of “Snatch of Sliphorn Jazz” accompanies a wild free jazz duet by saxophonist Jeff Lederer and drummer Wilson, while Carla Bley’s reading of “To Know Silence Perfectly” precedes and follows a thorough-composed canon where the individual entrances are spontaneously determined by the musicians. To fill out the suite, Wilson has set several Sandburg poems to his own music, and the dramatic (and witty) contrasts between the settings hold the listener’s attention. Country, gospel, funk, marches and a wealth of jazz styles appear side-by-side on Wilson’s album, and his amazing musicians (cornetist Ron Miles, guitarist and vocalist Dawn Thomson, Lederer—doubling on several reed instruments and harmonium—and bassist Martin Wind) embrace each style with confidence.

Wilson and Bloom also use different methods to integrate the music and poetry. Wilson’s setting of “Anywhere and Everywhere People” uses recurring  musical motives to emphasize the primary words of the poem (as read by Christian McBride). “As Wave Follows Wave” tells of new generations replacing the old, and after Wilson reads the poem, he adds a chorus of readers who recite the poem at their own speed, overlapping with each other in the process. Wilson’s most intriguing use of spoken word and music involves a recording by Sandburg himself. Wilson creates a virtual duet, using a looped recording of the poet reading “Fog” over an atmospheric drum solo. By the end of the track, we realize that the organizing motive of the drum solo perfectly matches Sandburg’s speech rhythms. On Bloom’s disc, the poetry readings generally appear as blocks at the beginning and ending of the movements, with improvisations and theme statements filling the remainder of each track. However, on the appropriately-titled “Say More”, Rush adds laughter, humming and a few repeated words over the quartet’s improvised music. At times, Bloom’s backgrounds evoke specific images from the poems—most notably, Dawn Clement’s single piano note which prefaces “One Note from One Bird” and the circus band imitation by Mark Helias’ arco bass and Bobby Previte’s snare drum at the opening of “Singing the Triangle”. Elsewhere, Bloom’s settings come from a deeper reading of the texts, as on “Alone and in a Circumstance”, a scene of Dickinson’s encounter with a spider, set with a plaintive soprano saxophone melody which could represent the animal, the woman, or both. Rush studied Dickinson’s life and poetry before the recording session, and she embodies Dickinson just as we imagine her: prim and proper most of the time, but able to gush with child-like excitement at the sight of a passing parade.

musical motives to emphasize the primary words of the poem (as read by Christian McBride). “As Wave Follows Wave” tells of new generations replacing the old, and after Wilson reads the poem, he adds a chorus of readers who recite the poem at their own speed, overlapping with each other in the process. Wilson’s most intriguing use of spoken word and music involves a recording by Sandburg himself. Wilson creates a virtual duet, using a looped recording of the poet reading “Fog” over an atmospheric drum solo. By the end of the track, we realize that the organizing motive of the drum solo perfectly matches Sandburg’s speech rhythms. On Bloom’s disc, the poetry readings generally appear as blocks at the beginning and ending of the movements, with improvisations and theme statements filling the remainder of each track. However, on the appropriately-titled “Say More”, Rush adds laughter, humming and a few repeated words over the quartet’s improvised music. At times, Bloom’s backgrounds evoke specific images from the poems—most notably, Dawn Clement’s single piano note which prefaces “One Note from One Bird” and the circus band imitation by Mark Helias’ arco bass and Bobby Previte’s snare drum at the opening of “Singing the Triangle”. Elsewhere, Bloom’s settings come from a deeper reading of the texts, as on “Alone and in a Circumstance”, a scene of Dickinson’s encounter with a spider, set with a plaintive soprano saxophone melody which could represent the animal, the woman, or both. Rush studied Dickinson’s life and poetry before the recording session, and she embodies Dickinson just as we imagine her: prim and proper most of the time, but able to gush with child-like excitement at the sight of a passing parade.

These albums represent new artistic heights for both Matt Wilson and Jane Ira Bloom. As mature composers and musicians, they know the value of letting their music develop over time. There are no superfluous tracks on either album, and it is clear that Bloom and Wilson took great care to ensure the best possible presentation of their completed works. Bloom’s double-album includes two track sequences; the programming of the first disc reveals the music’s unity, and the second, directed by the nature of the poetry, represents the order of movements when the suite is performed live. Both versions are equally effective. Wilson’s suite reflects his lifelong attraction to Sandburg: he was born in the same Illinois county as the poet, and “Charlie”, the owner of the “Prairie Barn” memorialized by Sandburg, was one of Wilson’s close relatives. Each album spotlights the best qualities of their leaders, while paying tribute to respected giants of American poetry. They are instant classics, and I’m certain they will be revered for many years to come.