Between 1975 and 1993, pianist Tommy Flanagan recorded six tribute albums featuring, in turn, the music of Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn, Bud Powell, Harold Arlen, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk and Thad Jones. These albums—it seems a stretch to call them a series—were recorded for four different labels, with only two of them recorded back-to-back, and an eleven-year gap between the last two. They were neither the first nor last of Flanagan’s tribute albums: early in his career, he had recorded an album of Richard Rodgers songs from “The King And I” under the leadership of trumpeter Wilbur Harden, and an album of Leonard Bernstein music under his own name; immediately after the Thad Jones album, he recorded a tribute to his former musical collaborator, Ella Fitzgerald. Yet, the tributes discussed here are linked by their focus on compositions, and by their appearance during a very productive part of the pianist’s career. For all but one of these tribute albums, Flanagan used a traditional piano trio (the exception was the Bud Powell tribute, which had only piano and bass). While Flanagan’s bassists remained fairly steady, each of the five trio albums had a different drummer, and the style of the percussionists helped to define each album.

Between 1975 and 1993, pianist Tommy Flanagan recorded six tribute albums featuring, in turn, the music of Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn, Bud Powell, Harold Arlen, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk and Thad Jones. These albums—it seems a stretch to call them a series—were recorded for four different labels, with only two of them recorded back-to-back, and an eleven-year gap between the last two. They were neither the first nor last of Flanagan’s tribute albums: early in his career, he had recorded an album of Richard Rodgers songs from “The King And I” under the leadership of trumpeter Wilbur Harden, and an album of Leonard Bernstein music under his own name; immediately after the Thad Jones album, he recorded a tribute to his former musical collaborator, Ella Fitzgerald. Yet, the tributes discussed here are linked by their focus on compositions, and by their appearance during a very productive part of the pianist’s career. For all but one of these tribute albums, Flanagan used a traditional piano trio (the exception was the Bud Powell tribute, which had only piano and bass). While Flanagan’s bassists remained fairly steady, each of the five trio albums had a different drummer, and the style of the percussionists helped to define each album.

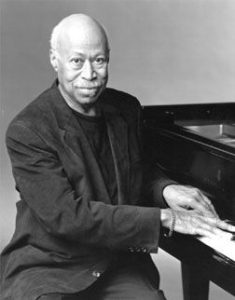

Since 1956, when he moved from Detroit to New York, Flanagan was a fixture on the recording scene. Fellow Detroiters Kenny Burrell and Thad Jones were the first to include Flanagan in their rhythm sections, and only four days after his New York recording debut, he recorded with Miles Davis. By the end of the year, Flanagan had participated in 17 recording sessions, which yielded classic albums like Davis’ “Collector’s Items”, “The Oscar Pettiford Orchestra in Hi-Fi” and Sonny Rollins’ “Saxophone Colossus”. He was a member of J.J. Johnson’s band until mid-1958, and in May 1959, he played on John Coltrane’s masterpiece, “Giant Steps”. Flanagan recorded two albums under his own name between 1957 and 1960, and co-led “The Cats” with Coltrane and Burrell in 1957. After working with Coleman Hawkins, and recording with a wide range of jazz giants between 1960 and 1963, Flanagan became Ella Fitzgerald’s accompanist and he would tour with her until the late 1970s.

When Flanagan recorded “The Tokyo Recital” in February 1975, it was the first  album issued under his own name in 15 years. Despite the title, the album was recorded in the studio, not in a concert setting. The album was conceived by producer Norman Granz as a tribute to Strayhorn, and seven of the nine songs were composed (or co-composed) by him. However, Ellington’s passing in May 1974 was still causing shock waves in the jazz community, and the addition of two Ellington compositions was doubtlessly included as a posthumous tribute. The trio, including bassist Keter Betts and drummer Bobby Durham, had worked together with Fitzgerald for over a year, and they were well-tuned to each other’s musical needs. Durham was a veteran of the Oscar Peterson Trio, and he pushed the rhythm by playing on top of the beat. Betts was a solid walking bassist with excellent time, and he was usually able to keep the tempo from rushing without dampening Durham’s energy.

album issued under his own name in 15 years. Despite the title, the album was recorded in the studio, not in a concert setting. The album was conceived by producer Norman Granz as a tribute to Strayhorn, and seven of the nine songs were composed (or co-composed) by him. However, Ellington’s passing in May 1974 was still causing shock waves in the jazz community, and the addition of two Ellington compositions was doubtlessly included as a posthumous tribute. The trio, including bassist Keter Betts and drummer Bobby Durham, had worked together with Fitzgerald for over a year, and they were well-tuned to each other’s musical needs. Durham was a veteran of the Oscar Peterson Trio, and he pushed the rhythm by playing on top of the beat. Betts was a solid walking bassist with excellent time, and he was usually able to keep the tempo from rushing without dampening Durham’s energy.

On the opening cut, Strayhorn’s “All Day Long”, Flanagan takes a sparkling solo which starts in single lines over Betts’ loping two-beat and then adds accenting chords when Durham moves the rhythm into a driving four. As the energy rises, Flanagan moves into a series of stunning block chords against Durham’s increasingly animated commentary. On “UMMG”, the tempo and format are similar to “All Day Long”, but the trio creates variety between the two performances as Durham stays on brushes, and Flanagan focuses on single-lines and occasional references to Strayhorn’s angular melody. Flanagan starts “Something to Live For” with a solo rendition of the verse, and his tender exposition of the melody is marked with the subtle use of parallel thirds and gently played block chords. The entire performance is only one chorus long, and in the last eight bars, Betts and Durham drop out to let Flanagan finish the piece on his own. “Main Stem” is the first Ellington composition on the program and the trio’s rendition is surprisingly aggressive. Betts’ double stops in the intro and theme are related to Ray Brown’s bass work with Peterson, and the rhythm style during Flanagan’s solo seems more akin to the Peterson trio than what we expect from Flanagan. The pianist digs into the keyboard here, and while he never loses his own identity, there is a deep funkiness in his solo that echoes Peterson’s style. Betts gets his first solo of the album, and he displays his rich sound and nimble technique. Flanagan brings in Durham’s solo with a strongly accented quote from Ellington’s original recording, and the drummer responds with a powerful, kinetic statement. “Daydream”, which concluded the LPs first side, is marked by active brushwork by Durham and a remarkable Flanagan solo where his lines develop out of each other with grace and elegance.

Flanagan retains Strayhorn’s block chord voicings on the theme statement of “The Intimacy of the Blues”, and while the tempo seems a little slow at the outset, Betts and Durham hold it steady throughout and create a deep groove for the pianist. Flanagan is the only soloist on this six-minute blues outing, and he crafts his solo with short delicious lines that flow as one. At key moments of the solo, he accentuates the lines with simple melodic harmony, and later, he echoes the block chords of the theme. There’s nothing flashy, and nothing extreme, but it all swings and it has impeccable musical logic. It’s hard to do something original with “Caravan”, but the trio’s alternating episodes of block-chord solo piano and full rhythm during the theme are quite effective, and Flanagan’s note-gobbling single-line solo swings mightily (listen carefully for a quick quote to “Shadow Waltz” and later, catch the reference to “Jubilation T. Cornpone”!). Durham loved fast tempos and while he doesn’t solo on “Caravan”, his relentless drive enlivens the performance, and when he and Betts come to a stop for the return of the theme, the effect is electric. “Chelsea Bridge” is performed in a comfortable walking tempo with Betts providing attractive counterpoint on bass, both on the theme and during the first half of Flanagan’s delicate solo. The closing version of “Take the A Train” builds steadily from beginning to end, with more striking lines from Flanagan, another horn-like solo from Betts and an explosive set of exchanges with Durham.

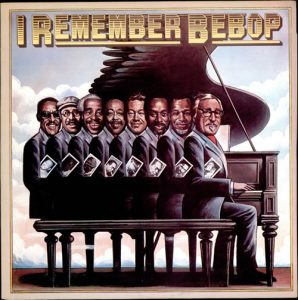

In November 1977, Flanagan was one of eight pianists who participated in the album “I Remember Bebop”. Each pianist was asked to play the music of a bebop giant that had influenced their work. Flanagan chose Bud Powell, and on November 3, he and Keter Betts recorded five Powell tunes. The liner notes of the original album were written by French pianist Henri Renaud, who also produced the album. He makes a big deal of the fact that all of the pianists played on the same Steinway grand and that all of the recordings were engineered by Stan Tonkel. I’m not sure if it was Tonkel’s recording or the instrument itself, but the piano sounds awful. The upper range sounds tinny and there’s no body to the sound at all (and this is from the original LP, so you can’t blame bad CD re-mastering!). Flanagan plays the tunes “Strictly Confidential”, “Dance of the Infidels”, “Bouncing with Bud” and “So Sorry, Please” with Powell’s introductions and stays true to the spirit of the originals. Betts has little to do but walk, and Flanagan plays fiery, concise solos that echo Powell but seem to end prematurely. “I’ll Keep Loving You” is played as a piano solo, and the sound of the instrument is much fuller as it is spread over the stereo soundscape. Flanagan plays the tune in a lush, rhapsodic style with lots of rubato and very little improvisation. Given better circumstances, Flanagan could have made a great album-length tribute to Bud Powell; this 15-minute cameo is at best, a disappointment.

In November 1977, Flanagan was one of eight pianists who participated in the album “I Remember Bebop”. Each pianist was asked to play the music of a bebop giant that had influenced their work. Flanagan chose Bud Powell, and on November 3, he and Keter Betts recorded five Powell tunes. The liner notes of the original album were written by French pianist Henri Renaud, who also produced the album. He makes a big deal of the fact that all of the pianists played on the same Steinway grand and that all of the recordings were engineered by Stan Tonkel. I’m not sure if it was Tonkel’s recording or the instrument itself, but the piano sounds awful. The upper range sounds tinny and there’s no body to the sound at all (and this is from the original LP, so you can’t blame bad CD re-mastering!). Flanagan plays the tunes “Strictly Confidential”, “Dance of the Infidels”, “Bouncing with Bud” and “So Sorry, Please” with Powell’s introductions and stays true to the spirit of the originals. Betts has little to do but walk, and Flanagan plays fiery, concise solos that echo Powell but seem to end prematurely. “I’ll Keep Loving You” is played as a piano solo, and the sound of the instrument is much fuller as it is spread over the stereo soundscape. Flanagan plays the tune in a lush, rhapsodic style with lots of rubato and very little improvisation. Given better circumstances, Flanagan could have made a great album-length tribute to Bud Powell; this 15-minute cameo is at best, a disappointment.

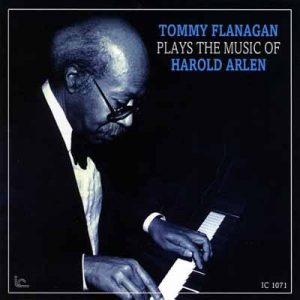

The following autumn, vocalist Helen Merrill produced “Tommy Flanagan Plays the Music of Harold Arlen”. Originally issued in Japan, and eventually released  in the US on Inner City, the album featured George Mraz on bass and the Modern Jazz Quartet’s Connie Kay on drums. Mraz’s elastic bass lines and Kay’s delicate cymbal work created an entirely new background for Flanagan, and the light, flexible approach is evident throughout the album. If the listener sensed creative tension between Flanagan and Durham on “The Tokyo Recital”, there is no such feeling on the Arlen album. Everyone seems relaxed, and the renditions have a breezy and joyous quality. On “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”, Flanagan spins out extremely long lines which start with enticing musical ideas and develop those ideas before the phrase ends. Flanagan developed this concept of developing ideas on the fly when he recorded with Sonny Rollins, and this subtle technique explains why Flanagan’s solos held together so well. “Over the Rainbow” has a double-time feel throughout, but that feel is only explicitly stated in about half of the performance. However, the placement of that feel in the introduction, bridge of the theme and in the solo section makes it discernible to the listener even in its absence. The feel also contributes to a general lightness that is rarely heard in versions of this standard. “A Sleepin’ Bee” has been a favorite of jazz musicians since its premiere in the mid-50s. Flanagan plays a solo version of the verse before segueing into a funky two-beat shuffle for the chorus. His first solo chorus opens with a variation on the theme before moving into bubbly single lines, and the second chorus features a rare excursion into locked-hands style. The track fades after the final chorus, but one wishes that this track would have gone on a lot longer. At this point, the listener might long for a ballad. We don’t really get one, but Flanagan’s extended solo intro to “Ill Wind” offers a brief change from the medium tempos of the other songs on the LP’s first side.

in the US on Inner City, the album featured George Mraz on bass and the Modern Jazz Quartet’s Connie Kay on drums. Mraz’s elastic bass lines and Kay’s delicate cymbal work created an entirely new background for Flanagan, and the light, flexible approach is evident throughout the album. If the listener sensed creative tension between Flanagan and Durham on “The Tokyo Recital”, there is no such feeling on the Arlen album. Everyone seems relaxed, and the renditions have a breezy and joyous quality. On “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”, Flanagan spins out extremely long lines which start with enticing musical ideas and develop those ideas before the phrase ends. Flanagan developed this concept of developing ideas on the fly when he recorded with Sonny Rollins, and this subtle technique explains why Flanagan’s solos held together so well. “Over the Rainbow” has a double-time feel throughout, but that feel is only explicitly stated in about half of the performance. However, the placement of that feel in the introduction, bridge of the theme and in the solo section makes it discernible to the listener even in its absence. The feel also contributes to a general lightness that is rarely heard in versions of this standard. “A Sleepin’ Bee” has been a favorite of jazz musicians since its premiere in the mid-50s. Flanagan plays a solo version of the verse before segueing into a funky two-beat shuffle for the chorus. His first solo chorus opens with a variation on the theme before moving into bubbly single lines, and the second chorus features a rare excursion into locked-hands style. The track fades after the final chorus, but one wishes that this track would have gone on a lot longer. At this point, the listener might long for a ballad. We don’t really get one, but Flanagan’s extended solo intro to “Ill Wind” offers a brief change from the medium tempos of the other songs on the LP’s first side.

“Out of This World” features a concentrated tight swing by the trio, and when Kay opens up on his ride cymbal, the sound seems too bright for the intense single-line solo that Flanagan creates. By the time the second chorus comes around, things are more in sync with Kay scaling back to match the emotional level of Flanagan’s developing solo. Not withstanding Frank Sinatra’s memorable recording, “One For My Baby” was composed with a light-hearted backbeat that seemed to contradict the lyric’s self-pity. Flanagan’s version retains the original feel and adds a bluesy edge to give it character. Unfortunately, this brief version only runs for one chorus, denying us of a Flanagan improvisation. “Get Happy” cooks from beginning to end, with a Flanagan solo that makes great use of small motives and occasional hints of the melody, an agile bass spot for Mraz, and crisp exchanges between Kay and Flanagan. “My Shining Hour” is played in an attractive two-beat arrangement that allows Flanagan to explore the song’s lovely changes and melodic ideas.

The album closes with a duet version of “Last Night When We Were Young” by Flanagan and Merrill. Flanagan plays the first chorus by himself and he effectively captures the intense drama of the song. He stretches the time here and there, and his dynamic range is quite impressive. I’m less enamored of Merrill’s singing. To be sure, her pitch is very good and her breath control seems better here than on her earlier recordings. However, she is not consistent in her use of vibrato and the contrast between her “dramatic” sound (loaded with vibrato) and her “pure” sound (completely without) is rather jarring when she employs them in succession near the end of the track.

Three and a half years passed before Flanagan recorded another tribute album. By this time, he was under contract to the German Enja label and Flanagan’s final three composer tributes would be recorded for that label. “Giant Steps (In Memory of John Coltrane)” includes five tunes from Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps”. This music had special significance for Flanagan in that he played on the original recordings of four of the compositions (the only songs Flanagan had not performed with Coltrane were the tribute album’s two ballads, “Central Park West” and “Naima”. The latter had appeared on “Giant Steps”, but played by Coltrane and a different rhythm section). George Mraz was still Flanagan’s bass player, and the drum chair was filled by Al Foster. Foster was best known for his funk work with Miles Davis, but he was equally adept at straight-ahead playing. His polyrhythmic style adds intensity to this Coltrane tribute.

Three and a half years passed before Flanagan recorded another tribute album. By this time, he was under contract to the German Enja label and Flanagan’s final three composer tributes would be recorded for that label. “Giant Steps (In Memory of John Coltrane)” includes five tunes from Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps”. This music had special significance for Flanagan in that he played on the original recordings of four of the compositions (the only songs Flanagan had not performed with Coltrane were the tribute album’s two ballads, “Central Park West” and “Naima”. The latter had appeared on “Giant Steps”, but played by Coltrane and a different rhythm section). George Mraz was still Flanagan’s bass player, and the drum chair was filled by Al Foster. Foster was best known for his funk work with Miles Davis, but he was equally adept at straight-ahead playing. His polyrhythmic style adds intensity to this Coltrane tribute.

The album opens with “Mister P.C.”, a minor blues dedicated to bassist Paul Chambers. Mraz plays a descending bass line against the original tune, and Flanagan’s opening solo is an intense brittle statement in stark single lines. Foster plays an active role in the three-way musical dialogue with bombs played on a large, seemingly untuned floor tom. Mraz was and is a more technical player than Chambers and his rhythmically-complex solo shows the advances in bass playing between 1959 and 1982. Foster’s exchanges involve heavy use of the tom-toms and he only engages the snare halfway through the series. “Central Park West” starts with Flanagan on solo piano and Mraz improvises a lovely countermelody over the pianist’s lush harmonies. Even when playing with brushes, as he does here, Foster still drives the trio with sudden moves into double-time. Flanagan, without much in the way of relaxed music on this set, makes the most of this piece and spins a pair of delicate improvisations. “Syeeda’s Song Flute” retains the stop-time feel of the original recording, but the solos are much more laid-back here. And while Foster is doing what he was hired to do, his interjections seem to get in the way of Flanagan’s long improvised lines.

“Cousin Mary” is another blues, and Flanagan sounds especially inspired, pouring out a seemingly limitless fountain of ideas in a nearly 4-minute solo. Foster is a little more reserved, but Flanagan bounces a few rhythmic ideas back to him during the piano solo. Coltrane wrote out the original bass line for “Naima”, and Mraz pays homage to Chambers with a lovely variation. Flanagan’s tender solo expands and develops motives from the original melody, and Mraz compliments the pianist with sensitive melodic responses. Back in 1959, Coltrane gave Flanagan a lead sheet of “Giant Steps” prior to the original session, but made no indication as to the tempo. Flanagan knew the changes for the recording, but was completely surprised by Coltrane’s frantic tempo, and the pianist’s solo on the original master is not one of his best. On the tribute album, he finally gets the chance to redeem himself on these devilish changes. Here, the improvised melodies that eluded him in 1959 are presented with supreme confidence and acuity. Foster shares in the glory, helping the pianist build to a mid-solo climax with a repeated rhythmic figure. Flanagan caps the performance with an impressive cadenza.

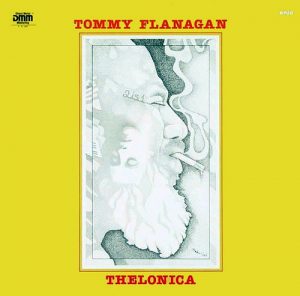

As Flanagan started recording his Coltrane tribute album on February 17,  1982, the Thelonious Monk tribute band, Sphere, was recording “Four In One”, its first album of Monk compositions. On the way home from the session, the members of Sphere discovered that Monk had died earlier that day. Flanagan doubtlessly heard the news around the same time, and his next album for Enja was a tribute to Monk and his longtime friend, the Baroness Nica de Koenigswarter. The album was titled “Thelonica” after a new Flanagan composition that combined the names of the two friends. Art Taylor, who played with Monk in 1954 and 1959, joined Flanagan and Mraz in the trio, and the track list included familiar and neglected Monk compositions from all periods of his career. “North of the Sunset”, a blues that Monk only recorded on a 1964 solo piano date, opens the set and Flanagan’s solo announces that this tribute will not be a maudlin affair, but a jubilant one with plenty of nods at Monk’s musical humor. And the strong rhythm that was such an important element of Monk’s groups is here, thanks to the tight pairing of Mraz and Taylor. Flanagan’s strongly fingered single-line solo on “Light Blue” brings out some minor voicing issues with the piano, but the clarity of his lines outweigh the technical issues. “Off Minor” was one of the pieces Taylor recorded with Monk at the pianist’s 1959 Town Hall concert. Flanagan’s solo drives forward with propulsion fueled by his own forceful delivery, Mraz’s unyielding time and Taylor’s active commentary. Taylor leads a brilliant set of exchanges with Flanagan that features the drummer’s lightning-fast technique and sharp imagination. “Pannonica” starts with Flanagan’s solo piano, and when the rhythm comes in, there are three active melodic lines, one from each of Flanagan’s hands, plus Mraz’s flexible bass. Flanagan’s style is closer to his own than Monk’s, but he and Mraz utilize Monk’s dictum of using the melody to create their solos.

1982, the Thelonious Monk tribute band, Sphere, was recording “Four In One”, its first album of Monk compositions. On the way home from the session, the members of Sphere discovered that Monk had died earlier that day. Flanagan doubtlessly heard the news around the same time, and his next album for Enja was a tribute to Monk and his longtime friend, the Baroness Nica de Koenigswarter. The album was titled “Thelonica” after a new Flanagan composition that combined the names of the two friends. Art Taylor, who played with Monk in 1954 and 1959, joined Flanagan and Mraz in the trio, and the track list included familiar and neglected Monk compositions from all periods of his career. “North of the Sunset”, a blues that Monk only recorded on a 1964 solo piano date, opens the set and Flanagan’s solo announces that this tribute will not be a maudlin affair, but a jubilant one with plenty of nods at Monk’s musical humor. And the strong rhythm that was such an important element of Monk’s groups is here, thanks to the tight pairing of Mraz and Taylor. Flanagan’s strongly fingered single-line solo on “Light Blue” brings out some minor voicing issues with the piano, but the clarity of his lines outweigh the technical issues. “Off Minor” was one of the pieces Taylor recorded with Monk at the pianist’s 1959 Town Hall concert. Flanagan’s solo drives forward with propulsion fueled by his own forceful delivery, Mraz’s unyielding time and Taylor’s active commentary. Taylor leads a brilliant set of exchanges with Flanagan that features the drummer’s lightning-fast technique and sharp imagination. “Pannonica” starts with Flanagan’s solo piano, and when the rhythm comes in, there are three active melodic lines, one from each of Flanagan’s hands, plus Mraz’s flexible bass. Flanagan’s style is closer to his own than Monk’s, but he and Mraz utilize Monk’s dictum of using the melody to create their solos.

“Ask Me Now” is played in a slow walking tempo, and Flanagan finds tenderness in the melody that may have eluded the composer. Monk first recorded his humorous self-portrait “Thelonious” at his first Blue Note session and later revived it for the Town Hall concert with Taylor. The original recording had touches of stride piano in Monk’s solo, and Flanagan includes a little stride in his unaccompanied introduction. Flanagan brings out his long single lines and illusions to “And the Angels Sing” and “Do You Know the Muffin Man” before Taylor contributes a rapid-fire drum solo. Flanagan gets another unaccompanied spot as the piece comes to a close. “Reflections”, one of Monk’s greatest ballads, is presented in an arrangement that echoes Monk’s own recordings. Both here and on “Ask Me Now”, Flanagan creates a hybrid of his own style and Monk’s, but while his solo on “Ask” was short and undeveloped, the solo on “Reflections” gives him time to examine the ways that Monk’s music influenced his own playing. “Ugly Beauty” was composed in the 1960s and is only now receiving its due as a Monk classic. Flanagan takes it as a waltz, letting the second half of the title outweigh the first. “Thelonica”, an unaccompanied piano solo, closes the set. Flanagan’s composition alludes to several Monk compositions, but the overall effect is a heartfelt salute from one great pianist to another.

Flanagan’s final composer tribute was recorded in 1993. Titled “Let’s Play the Music of Thad Jones”, it is not only the highpoint of these tributes, it is also one of Flanagan’s finest recordings. Recorded in Copenhagen with bassist Jesper Lundgaard and drummer Lewis Nash, it includes four tunes which Flanagan had played on Jones’ Blue Note recordings. Jones’ compositions were known for their unusual harmonic structures, and in an interview for the Mosaic reissue of those early recordings, Flanagan said that Jones “had a way of making things sound real familiar, but as far as I know, the [chord structures of his compositions] are all completely original”. Some of the melodies are tricky, too (as in the title cut, “Let’s”), and it is a testament to the outstanding musicianship of Flanagan and his trio that the entire hour-long disc was recorded in one day.

Flanagan’s final composer tribute was recorded in 1993. Titled “Let’s Play the Music of Thad Jones”, it is not only the highpoint of these tributes, it is also one of Flanagan’s finest recordings. Recorded in Copenhagen with bassist Jesper Lundgaard and drummer Lewis Nash, it includes four tunes which Flanagan had played on Jones’ Blue Note recordings. Jones’ compositions were known for their unusual harmonic structures, and in an interview for the Mosaic reissue of those early recordings, Flanagan said that Jones “had a way of making things sound real familiar, but as far as I know, the [chord structures of his compositions] are all completely original”. Some of the melodies are tricky, too (as in the title cut, “Let’s”), and it is a testament to the outstanding musicianship of Flanagan and his trio that the entire hour-long disc was recorded in one day.

“Let’s” was first recorded on a rejected Blue Note date in 1956, and then released in a remake version a year later. The stop-start rhythm of its main line follows its own logic, and Jones later incorporated it into his Basie big band chart “Not Now, I’ll Tell You When”. Flanagan’s version features tight ensemble figures by the trio, and a fiery solo by the pianist. Nash’s light, accurate and swinging drum work lifts the entire proceedings, and his solo exchanges here offer a stunning display of his arsenal of percussive effects. Lundgaard’s style is close to Mraz’s, but Lundgaard prefers to solo in the lower registers of his instrument. The smoothly-swinging “Mean What You Say” was recorded by Jones in big band and small group versions. Flanagan dances lightly over the keys in the early part of his solo, and then he signals a strengthened attack with sharply accented chords. The solo climaxes with a brief passage in locked hands style. Nash, always an attentive listener, picks up on Flanagan’s ideas instantly and uses his brushes to accentuate the pianist’s ideas. Nash’s solo brings back the dance motive, as he sounds like Fred Astaire on the drums. “To You” was part of the Basie band book, but its first issued recording was on the meeting of the Basie and Ellington bands. Flanagan also recorded the piece for the Manhattan Transfer’s collaboration with the Four Freshmen on the Transfer’s album, “Vocalese“. Flanagan’s trio version gives the slow ballad all the tenderness it deserves—and more. His rendition of the melody includes several of the countermelodies that made the instrumental and vocal versions so memorable.

“Bird Song” is quite reminiscent of Charlie Parker’s compositions, and the trio soars through this arrangement with abandon. Flanagan’s musical imagination takes him on a long and exciting journey through the changes, and the energy hardly flags when Lundgaard takes over. Nash’s crisp drum exchanges bring out strongly chorded responses from the pianist, and the performance ends with a surprising coda. “Scratch” is another song from the Blue Note days, but its title does not adequately describe the attractive late bop melody or its fine harmonic sequence. The title “Thadrack” sounds like a spiritual and its descending harmonic pattern adds character to the composition. Flanagan’s single lines sparkle as he develops and expands the improvised ideas, and the powerful swing generated by the trio makes you believe there are more than three people playing. The next three tunes, “A Child Is Born”, “Three And One” and “Quietude” were all part of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis band book. “Child” retains the arpeggiated style of Roland Hanna’s original version, but adds a slyly swinging vamp figure that’s unique to Flanagan. Ludgaard’s solo is a real gem and his most melodic of the date. “Three And One” is a fun tune to play, and the trio gives this one a spirited performance. Once again, Nash is right with Flanagan, accenting and enhancing the pianist’s thoughts with just the right amount of interplay. On “Quietude”, Flanagan’s superbly executed solo opens with delicate single lines and builds to a glorious chorus featuring sharply accented chords and leaping melody lines. The album closes with two early Jones pieces, “Zec” and “Elusive”. The former, with its jagged melody line, is taken at a brisk pace, with the leader providing another brilliant single-line solo on top of solidly swinging rhythm. And I love how Nash takes his final exchange on brushes to better prepare for the light-footed return of the melody! Despite its convoluted melody, “Elusive” proves to be an excellent finale to the set. Flanagan’s veiled reference to “Country Gardens” kicks off another fine solo spiced with witty melodic lines. Lundgaard picks up on an accompanying figure Flanagan plays beneath his bass solo, and Nash’s final exchanges of the album are another example of his superb musicianship and taste. From listening to this album, we can tell that these three musicians enjoyed performing with each other, and the utter joy of music-making transmits through the recording.

Tom Lord’s “Jazz Discography” lists 386 recording sessions for Tommy Flanagan, but only 46 of those were as a leader. Flanagan’s self-effacing manner may have made him suited as the master accompanist, but the flexibility that he gained in supporting other players made him the perfect pianist to salute other musicians. On these six tribute albums, he was able to display the strengths of his subjects, his trio, and himself. There aren’t many jazz musicians who can do that, and the passing of Tommy Flanagan in 2001 robbed us of one of the greats. He is fondly remembered by loyal jazz fans, and his low-key but vital contributions to the art of jazz piano made it a richer place for all of us. Tommy Flanagan deserves a tribute of his own.