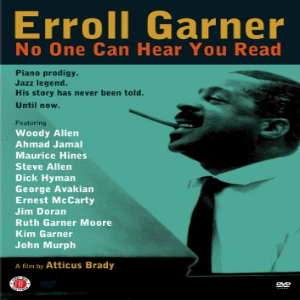

During an appearance on “The Tonight Show”, Johnny Carson asked Erroll Garner what made his music so recognizable. Garner didn’t really have an answer, so Carson directed the question to his band’s pianist, Ross Tomkins. Tomkins simply replied “Happiness”. While that answer lacks musicological significance, it was quite appropriate for a musician who once released an album called “The Most Happy Piano”. Garner was almost entirely self-taught, did not read or write music, and his style did not fit comfortably within jazz’s genres. Many pianists could mimic Garner’s style, but few—save for the actor Dudley Moore—played exclusively in the Garner fashion. As a consequence, Garner, who was probably the most popular jazz pianist of the 1950s, is nearly forgotten today. In an attempt to revive the memory of this most original pianist, filmmaker Atticus Brady has crafted an hour-long documentary, “No One Can Hear You Read”, which effectively balances discussions of Garner’s biography and musical style.

During an appearance on “The Tonight Show”, Johnny Carson asked Erroll Garner what made his music so recognizable. Garner didn’t really have an answer, so Carson directed the question to his band’s pianist, Ross Tomkins. Tomkins simply replied “Happiness”. While that answer lacks musicological significance, it was quite appropriate for a musician who once released an album called “The Most Happy Piano”. Garner was almost entirely self-taught, did not read or write music, and his style did not fit comfortably within jazz’s genres. Many pianists could mimic Garner’s style, but few—save for the actor Dudley Moore—played exclusively in the Garner fashion. As a consequence, Garner, who was probably the most popular jazz pianist of the 1950s, is nearly forgotten today. In an attempt to revive the memory of this most original pianist, filmmaker Atticus Brady has crafted an hour-long documentary, “No One Can Hear You Read”, which effectively balances discussions of Garner’s biography and musical style.

Brady has been working on this film since 1996, and he has gathered an impressive group of interviewees, including fellow pianists Dick Hyman, Ahmad Jamal and Steve Allen, bassist Ernest McCarty, producer George Avakian, biographer Jim Doran, and fans Woody Allen and Maurice Hines. The film clips may be the biggest surprise of the documentary. To keep costs down, most jazz films avoid clips from features and excerpts from high-profile television shows like Carson’s, but Brady includes bits of films like “Laura” and “Play Misty For Me” along with the Carson clip cited above, performance clips from the BBC’s “Jazz 625”, and concerts from Paris and Copenhagen.

Like Garner’s kaleidoscopic style, Brady’s well-paced film keeps the viewer engaged and never bogs down into technical discussions. Nancy Giles’ narration is simple and straight-forward, and most of the interviewees offer concise sound bites. Garner’s sister Ruth fills in most of the details on her brother’s childhood, and Garner’s illegitimate daughter Kim offers a touching memory of hearing her father in concert. To illustrate Garner’s piano style, Brady effectively cuts between the vintage clips and recreations by Hyman and Steve Allen. Allen explains Garner’s guitar-like approach to his left hand, and Hyman brilliantly dissects the big band/solo style of Garner’s right hand, but no one describes Garner’s time lag between the two hands, which was a central element of his swing (famously tagged “the Garner strut”). However, it’s very easy to hear that rhythmic style in the film clips. Garner’s free-form introductions are also discussed, and while there is some dissension about how Garner’s sidemen were clued into the identity of the tunes that followed, once again the film clip gives a very clear example of Garner’s methods. Overall, Brady’s film is quite accurate on the facts. When confronted with two very different stories on the origin of Garner’s hit song, “Misty”, Brady wisely includes one version in the feature and saves the other for the DVD bonus material (I would have used the bonus version in the main feature, but it’s not my movie).

The rest of the DVD bonus features include extended interviews with Hyman and Steve Allen, and a brief history of the production with Brady. Unfortunately, the full performance clips are not included, and only a brief discography (without record labels or catalogue numbers) is printed on the DVD jacket. Brady’s film does a great service to Garner’s legacy, and one would hope that a revival of Garner’s music will follow in the wake of this delightful portrait.