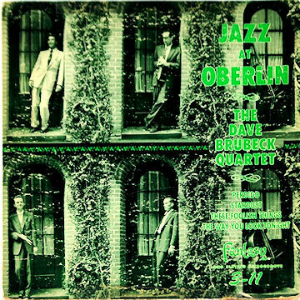

Paul Desmond loved to play on the changes to “The Way You Look Tonight”. He played it with the Dave Brubeck Octet and it became a regular part of early concerts by the Brubeck Quartet. Desmond revisited the piece on his 1962 collaboration with Gerry Mulligan, “Two of a Mind”, where he overdubbed a second alto line over the existing alto/baritone counterpoint. However, his greatest solo on these changes was recorded on March 2, 1953 on Brubeck’s “Jazz at Oberlin” album. I’ve written about this album and this solo before on our Retro Review page, and for background, you might want to go here and read my essay again. A few weeks ago, one of our readers told me that the complete solo had only been issued on the original 10-inch LP. At my request, he sent me the digitized version below (many thanks to Derry Music and the Desmond estate for allowing us to stream it here). Sure enough, the first full chorus of Desmond’s solo was edited out of the album.

The complete solo (from Fantasy 3-11, 10″ LP)

Editing is nothing new in jazz. It’s been around since the late 1940s, when tape replaced discs as the medium for capturing master recordings. Ironically, the recording technology that allowed for longer playing times on commercial discs was the reason for editing master tapes. At the time, there was a format war between Columbia’s 33 1/3 rpm LP and RCA’s 45 rpm EP. A 10-inch LP could fit up to 15 minutes per side, but a 7-inch EP could only hold 8 minutes per side. And thus was the apparent problem with the original issue of Brubeck’s Oberlin concert. Four of the five issued tracks from the concert fit tightly on a 10-inch LP, but “The Way You Look Tonight” ran nearly nine minutes on its own—too long to issue on an EP, but much too good to omit.

No one seems to remember the exact circumstances, but someone (thankfully, someone with musical training) edited out a chorus of Desmond’s solo in a way that has gone unnoticed until now. The recording starts with an introduction and 16 bars of melody with Desmond playing a baroque filigree against Brubeck’s melody statement (played in octaves). Unlike their later recording from College of Pacific, Desmond jumps into his improvisation at the bridge. On the well-known edited version, he continues for three-and-a-half choruses. The edited solo is a virtual tidal wave of ideas featuring extensive development of a motive from Stravinsky’s “Petrouchka”. On the complete version, Desmond uses more space and drops the energy level during the bridge of the first full chorus. He revitalizes the energy at the beginning of the next chorus at the point of the eventual edit.

The edited solo (from Original Jazz Classics 46, CD)

The edit creates a composite phrase that enhances the solo’s momentum. At the end of his first half-chorus, Desmond plays a descending sequential idea. He finishes the line by accenting a three-note motive. On the complete version, he rests for a few beats before continuing, but the edit cuts to a strongly marked “stutter” phrase (created with alternate fingerings for the same note)—or is it just crinkled tape around the splice?—and a rough inversion of the sequential motive. The edit creates a beat of space which makes it sound as if Desmond took a quick catch-breath before playing the stutter phrase, and it gives the impression of Desmond saying, “I’m not done yet!” The complete version balances the cool and intense moments of the solo (which was much more typical of Desmond’s style) while the edited version creates the illusion of steadily-building intensity with a seemingly endless flow of ideas.

In fact, the editor may have done Desmond a great favor by removing the less-intense first chorus from the solo. That may explain why this edited version has remained in the master tape, and has been the only version available for the last 50-plus years. Yet there is something innately human about the complete solo. The flow of ideas is still remarkable (especially the “Petrouchka” episode) but the shock of Desmond’s exuberance is tempered by the extra chorus. Certainly the complete solo should be heard by more people than the followers of this website and those who wisely hung on to their original 10-inch copies of “Jazz at Oberlin”. But if Concord Jazz wants to issue a definitive issue of this recording, they should include both the edited and complete versions. The inclusion of the missing chorus provides a different context than the highly effective edited version, and listeners should have the choice to pick which version they prefer.

Thanks to Samuel Chell, Vincent Pelote, Doug Pomeroy, Sean Singer, Chris Sheridan, John Hack and Doug Ramsey. Special thanks to Noel Silverman of the Paul Desmond Estate and Richard Jeweler of Derry Music for allowing us to stream the original recordings.