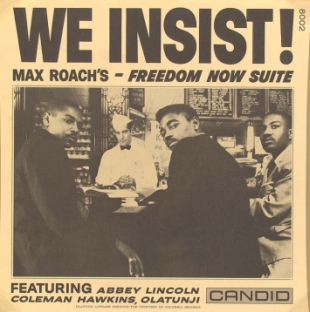

By the summer of 1960, the civil rights movement was gathering momentum, albeit in spits and starts. The “sit-in” movement had successfully desegregated the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, NC by July 25, but when Martin Luther King participated in a sit-in at the all-white Rich’s Restaurant in Atlanta the following October, he and 51 others were arrested as trespassers. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee had met for the first time on April 15, and the Freedom Riders commenced early in 1961. On August 31 and September 6, 1960, Max Roach brought in his quintet and several guest artists to the Nola studios in New York to record his “Freedom Now Suite”, the most overt political jazz recording made to that date.

By the summer of 1960, the civil rights movement was gathering momentum, albeit in spits and starts. The “sit-in” movement had successfully desegregated the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, NC by July 25, but when Martin Luther King participated in a sit-in at the all-white Rich’s Restaurant in Atlanta the following October, he and 51 others were arrested as trespassers. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee had met for the first time on April 15, and the Freedom Riders commenced early in 1961. On August 31 and September 6, 1960, Max Roach brought in his quintet and several guest artists to the Nola studios in New York to record his “Freedom Now Suite”, the most overt political jazz recording made to that date.

Roach’s quintet included Booker Little, a phenomenally talented trumpeter who had discovered his own style under Roach’s tutelage. Little had come to Roach’s group as a teenager, and his early recordings show him playing strings of sixteenth-notes with little melodic direction. During his three years with Roach, he learned how to pick the right notes and remove all of the excess. Throughout the album, Little’s solos project a deep feeling of melancholy that is still unique in jazz. Trombonist Julian Priester was an alumni of Sun Ra’s Arkestra, but was already on the studio scene when he joined Roach in 1959; bassist James Schenk had only appeared on a 1955 Bobby Banks date prior to “Freedom Now”, and tenor saxophonist Walter Benton had worked in Los Angeles from the mid-fifties, and had first recorded with Roach on a Clifford Brown jam session in 1954. However, the tenor saxophonist that made the greatest impact with his appearance on “Freedom Now” only played on the opening track. That was the legendary Coleman Hawkins, and his emotional solo on “Driva Man” not only added musical credence to the recording, but also added a multi-generational element to the personnel.

Without a doubt, the focal point of “Freedom Now” was vocalist Abbey Lincoln. Lincoln had made a well-publicized leap from the conservative supper clubs of the fifties to the progressive jazz scene of the sixties. She had removed most of the love songs and standards from her repertoire, and her voice took on a coarse tone, with anger that seemed to simmer right below the surface. Singing the politically charged lyrics of Oscar Brown, Jr., “Freedom Now” represented a breakthrough for both the vocalist and lyricist.

Thematically, the five movements of “Freedom Now Suite” divide into three sections. The first two movements, “Driva Man” and “Freedom Day” are set in the times surrounding the Civil War (although “Freedom Day” logically extends itself to the present and future times), the third movement is a three-part duet by Lincoln and Roach (of which more below) and the final two movements, “All Africa” and “Tears For Johannesburg”—which add percussionists Michael Olatunji, Ray Mantilla and Tomas DuVall to the group—deal with contemporary civil rights issues in the African homeland.

Accompanied only by a tambourine, Lincoln bites into the lyrics of “Driva Man” and when the band comes in, Hawkins is the dominant voice. His intense sound stands in stark relief against the piano-less background. As Nat Hentoff relays in his superb liner notes, Hawkins’ solo contained a reed squeak which the saxophonist insisted be left in the final recording: “When it’s all perfect, especially in a piece like this, there’s something very wrong”. “Freedom Day” sounds like it might be jubilant, but the sorrowful edge of Little’s lead trumpet tempers that feeling. Little’s solo has a lot of notes, but it is uncanny how the listener retains the striking color tones even amidst a flurry of notes. After impressive solos by Benton and Priester, Roach plays his only solo on the band portions of the suite. This solo develops ideas from a basic rhythmic motive, and seems to fall in line with the chronology of composed drum solos that Roach played later in his career.

The second side of the LP comprised the final two movements. As on the first side, the music opens with Lincoln accompanied only by drums. After the opening chorus, “All Africa” becomes a vocal duet between Lincoln and Olantunji with Lincoln singing the names of African tribes and Olantunji responding in the Yoruba dialect. These names are familiar to us now, but they must have been quite exotic to 1960 ears! The final three minutes of the movement are given to a long, but fascinating percussion interlude involving Roach and the three guest percussionists. “Tears For Johannesburg” follows without pause. There are no words to this final movement—Lincoln sings a plaintive legato vocalese that speaks volumes about the insanity of apartheid. I suspect that Little wrote the horn arrangements throughout this album; they speak with the same harmonic voice as his trumpet, and they are quite similar to the arrangements on his later album for Candid. His solo on “Tears” cuts right to the emotional bone, and while Benton’s solo seems rooted in bebop, it is by far his most emotional solo of the date. The other horns and percussionists build a frenzied background behind the tenor solo and continue it under Priester’s extended trombone solo. Finally, the drums and percussion take over, with Roach dominating the proceedings with impressive pyrotechnics. The horn line that follows melds into an improvised duet for trumpet and tenor, then moves back to written lines before the final fade-out.

I’ve saved the central Roach/Lincoln duet for last because it is the most controversial and the most problematic. Originally conceived and performed as music for a ballet, the “Triptych” is entirely wordless. The opening section called “Prayer” features Lincoln singing long legato lines on an “oo” vowel over Roach’s spare ostinato. As the lines intensify, Lincoln changes vowels to an “ee” and finally to “ah” as the section ends. Suddenly, the tempo and mood changes for “Protest” which consists of Lincoln screaming (not scream-like singing, real primal screaming) over Roach’s lightning-fast drums. Lincoln returns to normal singing techniques in “Peace” where she performs a group of sighs, laughs and short lines again to Roach’s rhythmic ostinato. Now, I’ve heard all of the arguments regarding this piece—it’s the central point of the entire suite and the screaming is the natural release of hundreds of years of racial inequality; no one but Abbey Lincoln could have performed this with such conviction; and (the dreaded) “you’re not supposed to like it”—and I agree with all of them. But no matter how insensitive it makes me sound, those 75 seconds of screaming have diverted me from listening to “Freedom Now Suite”. I suspect that there are many others who feel the same way. I’ve never been a fan of listening to something simply because it’s good for me. But there is something about making your work so repulsive that you lose the audience you wanted to address.

Just over a half-century later, we have an African-American president, and while Barack Obama has not been embraced by some Americans, he won the election by a substantial margin. If you call Obama’s election “Freedom Day”, then only Abbey Lincoln, Julian Priester, Ray Matilla (and possibly Tomas DuVall and James Schenck) lived to see it. Roach died before Obama’s campaign had gained much steam, Olantunji preceded Roach in death by four years, Benton passed in 2000, Hawkins in 1969, and Booker Little died just 13 months after recording “Freedom Now Suite”. The recording stands as a powerful monument to a difficult time we’d all rather forget.