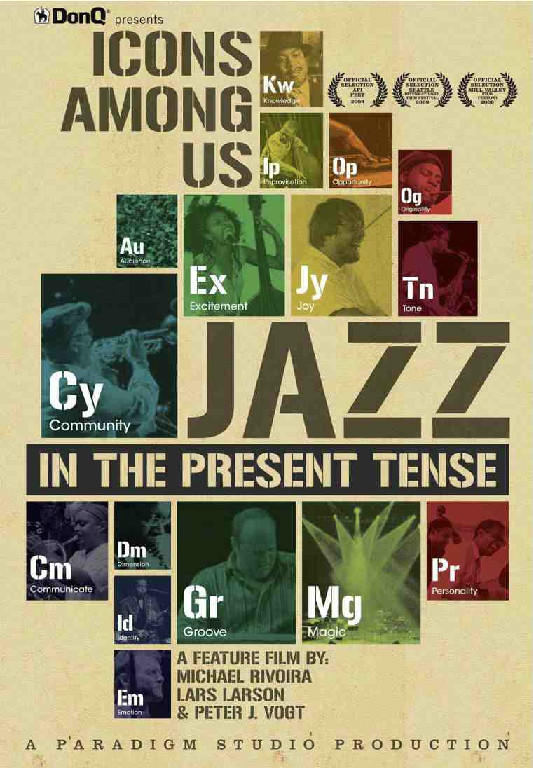

In a way, it’s an embarrassment of riches. The superb documentary “Icons Among Us: Jazz In The Present Tense”, which has been on DVD for the past year or so in its feature film incarnation, is now available in its original 4-hour television version as a 4-DVD/1 CD-ROM “educational” set (the CD-ROM is a 62 page study guide in PDF format). Even if you’re not part of an educational institution, you can buy the multi-disc set online for around 50 dollars. The feature film disc can had for about $20, but no one seems to offer an “all of the above” option (at least not now). In comparing the two versions, it is nearly impossible to recommend over the other as each version offers a unique presentation of the material. The feature film, running 95 minutes, is tightly formatted, and gives a concise overview of the current jazz scene. The TV version is 212 minutes, split over 4 episodes, and the subject matter meanders here and there, with discussions of important subjects popping up in random fashion over the course of the series. Naturally, the TV version is more comprehensive, with several key sequences not included in the feature film.

The film’s subject is a contentious one—the new styles of improvised music currently being created and developed in New York, New Orleans and various European locales—and co-directors Michael Rivoria, Lars Larson and Peter L. Vogt have the good sense to let their interviewees offer dissenting viewpoints. Further, the viewer may well agree with something that’s said early on in the film and later disagree with that same person. For example, Robert Glasper is entirely correct in his assertion that jazz in the 21st century needs to move past the music of Charlie Parker, yet he is completely unfair in dismissing the current European jazz scene because it is based on classical and folk music instead of blues and church music. The tight structure of the feature also helps to define the biases of the interview subjects. Seattle jazz critic Paul de Barros is seen about 15 minutes into the feature deriding the music of Bill Frisell because he thinks it doesn’t relate to contemporary culture (a specious argument that Frisell effectively diffuses). The next time we see de Barros is 38 minutes later as he praises Wynton Marsalis to the skies. Nothing wrong with the man having an opinion—after all, it is his job to do so—but without understanding his bias, we wonder why he was picking on poor Bill Frisell. (In the TV version, there’s a much longer wait between de Barros’ appearances: nearly 2 full episodes). However, the TV version also includes de Barros’ observation that arguments about the merits of progressive jazz musicians are good for the music in the long run—not only true for the music, but for this film as well.

The film’s subject is a contentious one—the new styles of improvised music currently being created and developed in New York, New Orleans and various European locales—and co-directors Michael Rivoria, Lars Larson and Peter L. Vogt have the good sense to let their interviewees offer dissenting viewpoints. Further, the viewer may well agree with something that’s said early on in the film and later disagree with that same person. For example, Robert Glasper is entirely correct in his assertion that jazz in the 21st century needs to move past the music of Charlie Parker, yet he is completely unfair in dismissing the current European jazz scene because it is based on classical and folk music instead of blues and church music. The tight structure of the feature also helps to define the biases of the interview subjects. Seattle jazz critic Paul de Barros is seen about 15 minutes into the feature deriding the music of Bill Frisell because he thinks it doesn’t relate to contemporary culture (a specious argument that Frisell effectively diffuses). The next time we see de Barros is 38 minutes later as he praises Wynton Marsalis to the skies. Nothing wrong with the man having an opinion—after all, it is his job to do so—but without understanding his bias, we wonder why he was picking on poor Bill Frisell. (In the TV version, there’s a much longer wait between de Barros’ appearances: nearly 2 full episodes). However, the TV version also includes de Barros’ observation that arguments about the merits of progressive jazz musicians are good for the music in the long run—not only true for the music, but for this film as well.

I don’t suppose Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center could be completely ignored in a project like this, but in a film that focuses on cutting-edge jazz, Marsalis and his conservative big band seem like an anachronism. They get nearly 9 minutes in the feature—almost 10% of the running time—and Marsalis uses some of his interview time to insinuate that the newer styles of jazz are a “corruption” of the music he prefers. While I applaud the filmmakers’ thorough approach in covering the current jazz scene, I wonder how they managed to omit Maria Schneider and her orchestra. Not only would have Schneider provided more contemporary big band music, but she would offer an important example of how marketing music has changed as it moved from the corner record store to the internet.

While the feature is excellent overall, it is not perfect. The TV version includes sequences by Gretchen Parlato, Lionel Loueke, the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, and e.s.t. that did not make the transition to the feature. There are valid comments made by Marco Benevento and Will Bernard, and thus, examples of their music are also included in the feature. However, I’m not so sure that Benevento’s group Garage a Trois and Bernard’s trio are necessarily the most appropriate representatives of the current jazz scene, especially when artists like Parlato and Loueke have already begun to make inroads in that same direction. The feature also alludes to a chasm between young and old jazz musicians, and insinuates that jazz mentoring died off with Art Blakey. The TV version demonstrates the exact opposite showing that Terence Blanchard and Greg Osby are active mentors for the young generation, and that Dave Holland and Chris Potter, representing a group one generation older, enjoy a similar type of musical relationship.

Undoubtedly, the feature’s greatest omission is the segment on e.s.t. and its pianist, Esbjorn Svensson. The filmmakers filmed e.s.t. on at least two occasions, and then re-interviewed the remaining members of the group after Svensson’s accidental death. The two musicians are clearly shaken by the loss of their friend and musical colleague, and wonder if they will ever find another opportunity to create music at the same level as they had with Svensson (The parallels to Bill Evans and Scott LaFaro are just plain eerie). Anchored by Richard Bona’s comment about the difficulty of replacing longtime band members and by fellow pianist Aaron Parks’ observation on how jazz reflects the personality of its players, this sequence is the best part of the series. Why it wasn’t included in the feature is beyond me.

The advertising tag for both versions of the film is “You will never look at jazz, art and life the same way.” For once, the hyperbole is true. Anyone with a love or an interest in jazz should see this film, even if only the feature version. For those who want a fuller picture of the current jazz scene (and have the patience for the slower pace), the TV version is the better choice. However, the best option may be “all of the above”. Are you listening, Indiepix?