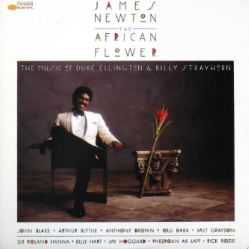

In 1988, as my Senior Honors project at the University of Northern Colorado, I developed and taught a semester-long jazz history course.  The musical examples for the course were included in a 23-cassette collection which chronicled the history of jazz from 1902 to the present. For the most part, selecting the 500 tracks for the tapes was fairly easy: between the unquestioned classic recordings and the ones I wanted to include, I usually had more music than would fit on the tapes, so the toughest part was figuring out what to omit. However, the final tape, which brought the music to the present day, was a little more challenging. I wanted to include musicians who were already established by 1988, and who I hoped would still be creative forces in the decades to come. Looking back at the playlist 28 years later, I picked well: Wynton and Branford Marsalis were well-represented, as were Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, Bobby McFerrin, and—performing as sidemen—Fred Hersch and Tom Harrell. The glaring exception was the track by flutist James Newton, taken from his Duke Ellington/Billy Strayhorn tribute album, “The African Flower”. Not only did I feel that Newton was an outstanding musician and arranger, I believed that many of his sidemen (including violinist John Blake, alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe, cornetist Olu Dara, vibraphonist Jay Hoggard, and drummer Pheeroan akLaff) would also become major innovators. At the time, it seemed a safe bet: “The African Flower” had already selected as one of the top albums of 1985, and all of the musicians were still very active on the jazz scene. The album also appeared on several best-of-the-80s jazz lists. However, few of the musicians on the album maintained their places in the jazz firmament.

The musical examples for the course were included in a 23-cassette collection which chronicled the history of jazz from 1902 to the present. For the most part, selecting the 500 tracks for the tapes was fairly easy: between the unquestioned classic recordings and the ones I wanted to include, I usually had more music than would fit on the tapes, so the toughest part was figuring out what to omit. However, the final tape, which brought the music to the present day, was a little more challenging. I wanted to include musicians who were already established by 1988, and who I hoped would still be creative forces in the decades to come. Looking back at the playlist 28 years later, I picked well: Wynton and Branford Marsalis were well-represented, as were Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, Bobby McFerrin, and—performing as sidemen—Fred Hersch and Tom Harrell. The glaring exception was the track by flutist James Newton, taken from his Duke Ellington/Billy Strayhorn tribute album, “The African Flower”. Not only did I feel that Newton was an outstanding musician and arranger, I believed that many of his sidemen (including violinist John Blake, alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe, cornetist Olu Dara, vibraphonist Jay Hoggard, and drummer Pheeroan akLaff) would also become major innovators. At the time, it seemed a safe bet: “The African Flower” had already selected as one of the top albums of 1985, and all of the musicians were still very active on the jazz scene. The album also appeared on several best-of-the-80s jazz lists. However, few of the musicians on the album maintained their places in the jazz firmament.

Despite the varied fortunes of the musicians, “The African Flower” still holds up very well. Newton’s playlist includes selections from Ellington’s early days at the Cotton Club through his lesser-known works of the mid-sixties. Juxtaposing the familiar with the obscure, Newton’s arrangements retain the feel of the original scores. The opening track, “Black and Tan Fantasy” features Dara’s growling muted cornet and Newton’s flute in tight thirds over the jungle background of Roland Hanna (piano), Rick Rozie (bass) and Billy Hart (drums). Newton orchestrates searing backgrounds for Blythe and Blake, and there is a great explosion of sound before Dara’s personal (but still tradition-bound) solo. The band drops out when Hanna starts a funky stride solo. Newton takes over with a striking improvisation which he sings and plays simultaneously. The rhythm digs in as Newton builds his solo and segues into the stop-time final chorus of the composition. After the closing quote from Chopin’s Funeral March, Newton and Dara add a final wail to finish the arrangement. “Virgin Jungle” was my selection from the album for the jazz history tapes, and I still consider it the highlight of the disc. Originally a Jimmy Hamilton feature from Ellington’s “Concert in the Virgin Islands”, the work is a rarity in the Ellington/Strayhorn catalog, as it is built on a single chord. The Ellington version seems to run out of steam after 3 minutes or so, but the Newton arrangement harbors an abundance of energy throughout its 11-minute duration. Hart remains on the drum set with akLaff playing talking drums. After the opening drum duet, Newton’s setting creates an exotic atmosphere with plaintive calls on flute, bass and violin, followed by rich chords on vibes. The opening melody is delivered with brio by the front line, followed by a moody episode of collective improvisation. Hoggard plays a fluid opening solo in close consort with Rozie’s bass. Blake’s violin solo is intense and agitated with highly effective double stops. Newton keeps the intensity high, while only using the multiphonics on a few occasions. While the previous solos had featured a background figure based on the last phrase of the original melody, the group also reprises a little of the collective improvisation behind Newton. Blythe follows with a full-throated sound and melodic ideas that move between inside and outside playing, and then Dara closes the horn solos with an adventurous and mournful statement on muted cornet.

Newton connects the worlds of Strayhorn and Mingus for the last track on the first side, “Strange Feeling”, originally a movement from “The Perfume Suite”. Milt Grayson (the only musician on the album who actually performed with Ellington) provides a darkly-colored vocal over Newton’s highly vocalized arrangement. Ellington’s haunting “Le Fleuette Africaine” opens the second side. The rich colors come from the combination of Rozie’s fluttery bass line, and the delicate interplay between Newton’s pure flute, Blake’s lightly played violin and Hoggard’s understated vibraphone chords. Within a track of only four minutes, Newton, Blake and Hoggard each contribute remarkably complete and fulfilling statements. akLaff (now on drum set) fuels a brightly swinging jam on “Cottontail” which features an opening solo by Blythe which bursts with raw emotion, followed by a spritely duet between Hanna and Hoggard, and a final spot by Newton, where the flutist rides right on top of the beat as he propels the ensemble swing to ecstatic heights. “Sophisticated Lady” is an unaccompanied solo by Newton, and his performance—which excels on both a technical and emotional level—shows that he was a rightful successor to the legacy of Eric Dolphy. The album’s final track, Strayhorn’s “Passion Flower”, opens with a lush introduction by Hanna. After another deeply-hued passage by Newton, Blythe takes center stage, playing the melody originally intoned by Johnny Hodges, but with a harder-edged tone and none of Hodges’ trademark glissandos. Hanna contributes an impeccably-constructed solo in the center chorus, followed by another strongly vocalized ensemble passage. Newton plays a hyperactive half-chorus before Blythe returns to close the album.

So what happened to the members of this remarkable ensemble? For a few years, many of them continued their careers as expected, recording albums on their own and appearing as sidemen on others. In the early 2000s, things started to unravel for some of the musicians. Death took Hanna and Grayson in the first half of the decade, and Blake passed away in 2014. Blythe developed Parkinson’s disease (and a website devoted to paying his medical expenses can be found here). Dara collaborated with his son, the hip-hop artist Nas, but has not recorded a jazz album in several years. Hoggard’s website states that he has a new album out, but I have been unable to find a place to purchase it. Hart is still going strong, recording albums for ECM, and akLaff sells his current albums on his website. Newton recorded a superb follow-up album for Blue Note, “Romance and Revolution” (with a great version of Mingus’ “Meditations on Integration”) and had a highly publicized court battle with the Beastie Boys over a recording/sampling dispute. A long-time educator, Newton has recently turned his energy to composing sacred choral works, including a setting of the St. Matthew Passion. The most impressive connection to the Ellington/Strayhorn legacy has come from Anthony Brown, who plays maracas and finger cymbals on “The African Flower”. Brown’s Asian-American Orchestra recorded a dramatically re-written version of “The Far East Suite” incorporating several instruments from Japan and the Middle East. Brown’s settings represent the most significant expansion of an Ellington/Strayhorn work ever attempted. It is not for all tastes, but it is probably the greatest tangible legacy from “The African Flower”.