When Astor Piazzolla was growing up in Argentina, he had three great musical passions: tango, Bach and jazz. He had played in traditional tango orchestras since he was 15, and as he developed as a composer, he tried to incorporate his three musical passions into one style. His work was considered too radical for the Argentinean tango audiences and eventually Piazzolla decided to abandon tango and write in the classical style. One of his orchestral works won him a scholarship to study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. As she did with several of her students, Boulanger encouraged Piazzolla to embrace the music of his native land.

When Astor Piazzolla was growing up in Argentina, he had three great musical passions: tango, Bach and jazz. He had played in traditional tango orchestras since he was 15, and as he developed as a composer, he tried to incorporate his three musical passions into one style. His work was considered too radical for the Argentinean tango audiences and eventually Piazzolla decided to abandon tango and write in the classical style. One of his orchestral works won him a scholarship to study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. As she did with several of her students, Boulanger encouraged Piazzolla to embrace the music of his native land.

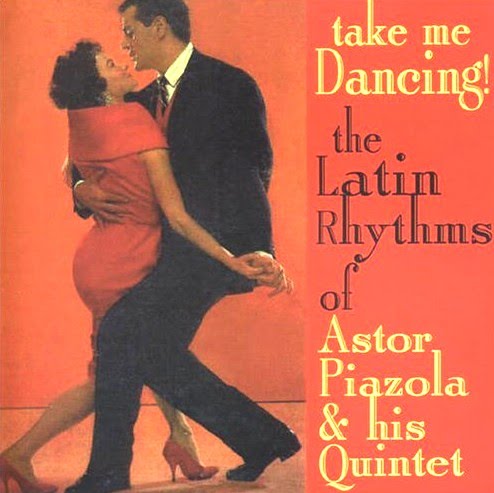

Piazzolla went back to Argentina and created a new style called tango nuevo which attempted to add counterpoint, improvisation and jazz rhythm to the traditional tango style. Counterpoint was easy enough to add, as was leaving space in the compositions for improvisation, but jazz rhythm proved to be Piazzolla’s greatest challenge. In 1959, while living in New York City, Piazzolla recorded an album called “Take Me Dancing” which he believed would launch a new style of jazz tango. The record was an artistic and commercial failure, and the reason is quite obvious: Piazzolla took out all of the tango’s distinguishing features and replaced them with light Afro-Cuban percussion. It all sounds like bad lounge music, and Piazzolla not only disavowed the record, he made few attempts to bring jazz rhythm into his music in later years.

Over the last few years, bassist Pablo Aslan has tried to create the jazz/tango fusion that eluded Piazzolla. When he found a used LP copy of “Take Me Dancing” in a Buenos Aires record store, Aslan was initially put off by the percussion, but later, he re-examined the recording and found that the compositions were quite strong and that the music could lead to the mixture of jazz and tango that both he and Piazzolla had sought. Along with bandoneonist Nicolas Endrich and pianist Abel Rogatini, Aslan transcribed the original Piazzolla arrangem ents from the vinyl, and then re-arranged them for his group, which also included trumpeter Gustavo Bergalli and Piazzolla’s grandson, drummer Daniel Piazzolla. In May 2011, the group went to Buenos Aires to record new versions of nine of the songs from “Take Me Dancing” along with the Piazzolla original “La Calle 92”.

ents from the vinyl, and then re-arranged them for his group, which also included trumpeter Gustavo Bergalli and Piazzolla’s grandson, drummer Daniel Piazzolla. In May 2011, the group went to Buenos Aires to record new versions of nine of the songs from “Take Me Dancing” along with the Piazzolla original “La Calle 92”.

The resulting album, “Piazzolla in Brooklyn” represents one of the finest attempts to mix these two musical styles. The key to its success may be that all of the musicians are equally conversant in tango nuevo and contemporary jazz. Specifically, Aslan’s quintet plays post-bop, a type of music that didn’t exist in 1959 when Piazzolla cut his original album, and because post-bop is not required to swing, the younger Piazzolla is able to play percussion patterns that incorporate both a pulsating jazz beat and the distinctive tango rhythm. Over this unique percussion base, the other band members are able to improvise in jazz style, tango style or their own mixture of both. “La Calle 92”, which is—of all things—a modified blues, veers back and forth between the styles, finding its happy medium during the solo section. The younger Piazzolla is a dynamic drummer with astonishing technique—it’s a shame his grandfather never included a drummer in his quintet.

As the group progresses through the songs from “Take Me Dancing”, we can hear the compositional strength that Aslan found when he revisited the original album. True to its title, “Counterpoint” has superb multiple lines, and Rogatini’s sparkling piano solo melds effortlessly back into the written line. I’m particularly impressed with the rhythm on “Dedita”, which perfectly encapsulates this unique fusion. Quite simply, it is a rhythm that can be heard in two different ways, depending on how the listener groups the beats in his brain. In addition to Piazzolla’s originals, the original album included his arrangements of three jazz standards. Aslan has recorded two of them, “Laura” and “Lullaby of Birdland”. The former has a marvelous countermelody and an ingenious melodic variation, but the latter is even more astounding, with its surprising rhythmic re-arrangement of the melody.

Rogatini plays his longest (and best-crafted) solo of the date on Piazzolla’s “Oscar Peterson”, which is more of a tribute to the jazz pianist than a re-creation of his style. Enrich gets more solo time on “Plus Ultra” and “Show-Off”, and the unique sound of his bandoneon enlivens the proceedings. He is not as fluent of an improviser as Bergalli, but the contrast of the trumpeter’s open tone with the constricted sound of the bandoneon is very effective. Aslan’s solos throughout the album display his beautiful tone. His time within the rhythm section is quite steady, but at times, that rhythmic stability does not carry into his solos. His solo in the early sections of “La Calle 92” nearly destroys the balance of the fused rhythm styles.

While there have been other attempts to fuse jazz and tango, “Piazzolla in Brooklyn” may be the best-realized of them all. It may not appeal to tango or jazz purists, but for those with open ears and minds, this album offers a wealth of extraordinary music. Astor Piazzolla would be proud.

Thanks to Barbara Paris for her tango expertise.