For nearly a half-century—from the day in 1877 when Thomas Edison first shouted “Mary Had a Little Lamb” into a prototype cylinder, to 1925 when microphones were first added to recording studios—the craft of sound recording was crude and imperfect. To make records in those days, a limited number of musicians gathered in hot, airless rooms facing a large horn embedded in the studio wall. The other end of the horn was connected to a cutting stylus which etched the sound waves into a wax disc. There was no way to edit the recordings, either due to musical errors, or outside noises (such as the freight trains which frequently roared past the Gennett studios). To maintain sound balance and avoid distortion, musicians were scattered about the room, with the loudest players situated as far from the horn as possible. Drummers did not need to bring their entire kits, for they usually played their parts on woodblocks. And all of that work resulted in recordings with little to no bass response, a boxy sound, and limited dynamics.

those days, a limited number of musicians gathered in hot, airless rooms facing a large horn embedded in the studio wall. The other end of the horn was connected to a cutting stylus which etched the sound waves into a wax disc. There was no way to edit the recordings, either due to musical errors, or outside noises (such as the freight trains which frequently roared past the Gennett studios). To maintain sound balance and avoid distortion, musicians were scattered about the room, with the loudest players situated as far from the horn as possible. Drummers did not need to bring their entire kits, for they usually played their parts on woodblocks. And all of that work resulted in recordings with little to no bass response, a boxy sound, and limited dynamics.

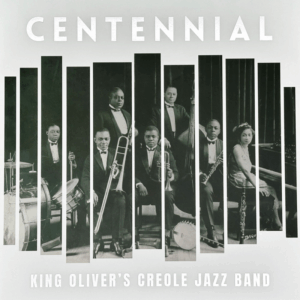

The improvisatory nature of jazz meant that the music had to be recorded to be disseminated. In April 1923, one of the premier groups in jazz, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band took a long train ride from Chicago to Richmond, Indiana to create their first recordings. The session at Gennett represented the recording debut for every member of this band, including lead cornetist Oliver, his young protégé, Louis Armstrong, trombonist Honoré Dutrey, clarinetist Johnny Dodds, pianist Lil Hardin, banjoist Bud Scott, and drummer Baby Dodds. Over two days, the band successfully recorded nine sides, and by the end of the year, they had created a total of 37 recordings, made for four different companies. Those 37 tracks document the Oliver band’s extraordinary skill at collective improvisation, and mark Armstrong’s rapid artistic growth.

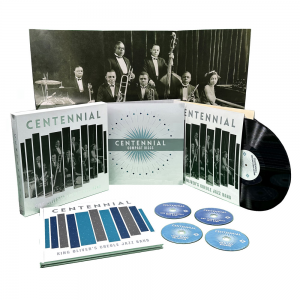

Listening to the Oliver recordings was a challenge that every jazz history student had to endure. The sound was dim and unfocused, with lots of echo added for LP reissues. Listeners were encouraged to listen through the scratches and post-production effects to hear the remarkable music contained within the dusty grooves. Needless to say, it was a hard sell. That situation has now been rectified through an amazing new collection from Archeophone Records, “Centennial“. Co-producer and restoration engineer Richard Martin has created new remasters of the 37 Oliver tracks which greatly reduce all of the disc’s technical issues and reveal the inner beauties of this incredible music. While Martin’s work has resulted in the clearest editions to date of the Oliver tracks, it is important to understand that this is neither stereo nor anything resembling contemporary recording. But these classic recordings have a new sheen and clarity. Deep within the 80-page hardback book of liner notes and photos, Armstrong expert Ricky Riccardi remarks about one of Martin’s remasters which now reveals a bass saxophonist previously hidden within the scratch and noise of the ancient 78.

“Centennial” includes all 37 Oliver tracks, sequenced in release order, on LP and CD. But Martin, Riccardi, and co-producer Meagan Hennessy did not stop there. A third CD called “Louis’ Record Collection” addresses the questions of Armstrong’s influences. Citing recordings from Armstrong’s personal library now located at the Armstrong Archives in Corona, Queens, New York, Riccardi leads us through a series of tracks featuring opera excerpts, comedy routines, concert bands, and pop songs which all had a lasting effect on the trumpeter. The recordings date from an 1891 cylinder to a 1921 vaudeville routine, and just like the Oliver sides, the sound is clear and consistent throughout the disc. There are two examples of the great operatic tenor Enrico Caruso, and while many engineers have attempted to restore the vibrancy in these discs, no one has done it better than Martin. Oliver’s contemporaries are examined in Disc 4, “Joe’s Jazz Kingdom.” This disc provides the rare opportunity to hear now-forgotten trumpeters such as Johnny Dunn, Frank Guarente, Jules Levy Jr., and Elmer Chambers. Their presence in this set reminds us that many musicians contributed to the development of jazz, but never received their due recognition. Hearing their music with improved fidelity will certainly help their legacies.

Martin’s audio restoration process began in the analog world, by locating the cleanest available copies of the original records, and establishing the disc’s proper playing speed (as not all shellac discs played at 78rpm). He also corrected inherent problems like off-center pressings and extraneous surface noise. Martin then chose a stylus that could best read the grooves, and used a stereophonic pickup so that each side of the groove—which generally experienced different types of wear—could be isolated. Once all of the preparations were complete, the music was transferred into high resolution digital format, where the audio could be restored through several highly specialized applications. The digital systems were closely monitored so that all of the musical content remained intact. The digital tools allowed more precise editing than in analog formats, including isolating a sonic portion of one channel (for example, the treble range) and mixing it with the remaining sounds from the other channel. Martin’s experience with the acoustic recording process—Archeophone releases little else—provided the necessary knowledge to recreate a soundscape reminiscent of the original studios, which as Martin notes, all had unique sonic characteristics.

If the technical jargon above is hard to understand, the simple solution is to simply listen to samples of the new restorations. Here is a brief promotional video (click the video tab) featuring excerpts from the rarest Oliver side, “Zulu’s Ball” (only one copy has survived!) and “Tears” with a brilliant early solo by Armstrong. Compared to every other issue, including the original 78, the sound is breathtaking. (The other video is Riccardi’s unboxing video, which gives an idea of the set’s size). Because it restores crucial elements of jazz history, “Centennial” may well be the most profound reissue of this or any other year. With a list price over $100, the set is not cheap, but it is an essential collection for jazz historians and fans alike. This is the true headwater of the jazz river; it all flows from here.