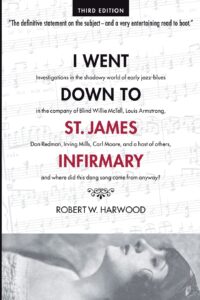

Whenever the great jazz trombonist Jack Teagarden played “St. James Infirmary“, he would tell the audience that it was the oldest blues he had ever heard. Like many public domain songs, we do not know who composed it, the circumstances surrounding its creation, or how sounded in its original version. More than likely, the song was not written down for many years, and by the time it was notated, there had been significant changes to both words and music made by other singers. It has appeared in print and on recordings under several titles, and there is a long list of pretenders who have falsely claimed authorship for the sole purpose of obtaining a copyright. For nearly two decades, author Robert W. Harwood has traced the origins and iterations of this classic song. The third edition of his book “I Went Down to St. James Infirmary” (Genius) offers a thorough history along with chronicles of the elements of the music business (sheet music, minstrelsy, song-plugging, recordings) which developed in the early 20th century.

Whenever the great jazz trombonist Jack Teagarden played “St. James Infirmary“, he would tell the audience that it was the oldest blues he had ever heard. Like many public domain songs, we do not know who composed it, the circumstances surrounding its creation, or how sounded in its original version. More than likely, the song was not written down for many years, and by the time it was notated, there had been significant changes to both words and music made by other singers. It has appeared in print and on recordings under several titles, and there is a long list of pretenders who have falsely claimed authorship for the sole purpose of obtaining a copyright. For nearly two decades, author Robert W. Harwood has traced the origins and iterations of this classic song. The third edition of his book “I Went Down to St. James Infirmary” (Genius) offers a thorough history along with chronicles of the elements of the music business (sheet music, minstrelsy, song-plugging, recordings) which developed in the early 20th century.

With its sorrowful, death-centered lyrics and its simple blues harmonies, “St. James’ Infirmary” has been performed in nearly every music genre, including jazz, blues, folk, and country. In a preface titled “Late-Breaking News”, Harwood announces a further connection that encompasses poetry, visual art, and opera, through the 19th-century poem, “The Face on the Bar Room Floor“. The poem inspired a Depression-era artist to paint a woman’s portrait on the floor of the Teller House Bar in Central City, Colorado. In turn, the painting inspired a one-act opera composed by Henry Mollicone, which is performed every summer by the Central City Opera. The final performance of every season is performed in the Teller “Face” Bar with the original painting serving as an active part of the dramatic action.

Even the earliest known incarnation of “St. James Infirmary”—known then as “The Unfortunate Rake” or “The Unfortunate Lad”—the story is told by a dying man whose demise (in this case, venereal disease) was caused by his sweetheart. He is left for dead outside a hospital, and after airing his complaints about his condition, he asks for an elaborate funeral with pallbearers, weeping maidens, roses, and a band with muffled drums. Harwood based the first edition of his book on ties between this early song and “St. James” but has since withdrawn that argument, noting a stronger connection between “Rake”/”Lad” and the cowboy song “Streets of Laredo“. Still, it is hard to miss the obvious similarities in tone (although we can be sure that these lyrics predated the blues). A 1902 Harvard University song added the lament to the victim’s sweetheart, “Let her go, God bless her”. In 1927, the poet Carl Sandburg published “The American Songbag“, a collection of folk songs he had heard over the previous twenty years. The collections’ two versions of “Those Gambler’s Blues” establish the blues structure, and tell of the sweetheart being at the infirmary—here “St. Joe’s”—and “stretched out on a long white table, so pale, so cold, so fair”. The male victim is now a gambler and his funeral requests now include a hat, box-back coat, and “a twenty-dollar gold piece on my watch chain, so the boys will know I died standing pat.”

Another version of the song, now titled “Gambler’s Blues”, was “co-composed” somewhere around 1924 by a drummer and singer from Arkansas named Carl Moore, and his then-employer, bandleader Phil Baxter. Moore eventually became a bandleader touring the Midwest, where he pleased audiences with yodeling and comedic impersonations of a country preacher. “Gambler’s Blues” was recorded in February 1927 by Fess Williams, and there are many similarities to the Sandburg version. Porter Grainger was a Black composer and pianist who, in 1927, copyrighted a song called “Dyin’ Crapshooter’s Blues”, which included many of the funeral requests from “St. James”. This version was recorded in 1940 by the blues singer Blind Willie McTell, and claimed by McTell as his own. The Louis Armstrong recording of December 1928 was the first recording to use the “St. James” title. It was arranged by Don Redman—and OKeh Records gave him an erroneous composer credit on the original label! The Armstrong recording, with only three verses of lyrics, was the hit version that influenced the majority of listeners. Irving Mills had secured publishing rights around the same time as Armstrong’s recording, and Mills soon published his own version with composer credit going to Joe Primrose (a Mills pseudonym).

With all of these competing versions (including a few more not discussed above), a lawsuit seemed inevitable. A recording by Gene Austin, which ironically used the public domain lyrics from the Sandburg version, spurred Mills to instigate a lawsuit in the New York Supreme Court. Harwood details the testimony of all the witnesses. Despite overwhelming evidence that none of the claimants or witnesses had written the song and that the song had existed for decades in public domain, Mills was allowed to maintain his title and copyright over “St. James’ Infirmary”. All of that legal wrangling will be moot within the near future, as all of the above copyrights will expire by January 1, 2026. In a way, the song has already won the battle, as most recordings of “St. James” are listed without a composer credit, and with the publishing status P.D.

Since the main arguments of Harwood’s book are about the copyright and publishing of “St. James Infirmary” and its offshoots, this book may also lose some of its purpose in the coming years. So perhaps it is time for a general celebration of this song, and the diversity of its recorded versions. Many of these recordings can be accessed online (and as I am still committed to physical media, I would welcome a boxed CD set with notes by Harwood). Listening is an essential part of the “St. James’ Infirmary” story. As one of the few songs that has stretched across stylistic boundaries, a comprehensive genre-crossing anthology could unite the various strains of American music towards the utopian melting pot. And we could use a little unity right about now.