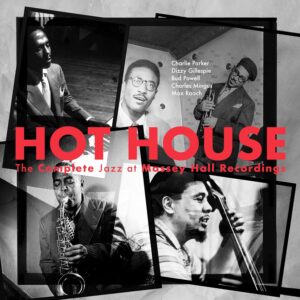

Competition is an omnipresent element in the arts. On a small scale, a judicious bit of one-upmanship can inspire artists to a greater performance. On the grand scale—especially when words like “greatest” and “best” are thrown about—the very presence of competition can set unreasonable goals for the audience—and retrospectively, the performers. Both sides of this issue can be heard in the music  recorded in Toronto on May 15, 1953, and newly reissued on Craft’s double CD, “Hot House: The Complete Massey Hall Recordings“. On a previous reissue, this all-star concert, featuring Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach, had the dubious honor of being titled “The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever”. For bebop lovers, this concert may indeed be the greatest of all time (although “favorite” might be more appropriate for a personal opinion), but the fans of a traditional ensemble called “The World’s Greatest Jazz Band” would probably disagree—especially since a few members of that band battled the boppers head-to-head on the “Bands for Bonds” radio show. If we narrow the title to “Greatest Modern Jazz Concert”, or even better, “Classic Charlie Parker-Dizzy Gillespie Live Recordings”, we may still have a few dissenters, owing to other recordings issued since the Massey Hall concerts, including the spectacular Town Hall concert of June 22, 1945, where Diz, Bird, Max, Al Haig, and Curly Russell essayed the bop repertoire to a young and enthusiastic audience, or the brilliant March 31. 1951 broadcast where Diz, Bird, Bud, Tommy Potter, and Roy Haynes blew the roof off Birdland with dazzling updates of bop standards.

recorded in Toronto on May 15, 1953, and newly reissued on Craft’s double CD, “Hot House: The Complete Massey Hall Recordings“. On a previous reissue, this all-star concert, featuring Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach, had the dubious honor of being titled “The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever”. For bebop lovers, this concert may indeed be the greatest of all time (although “favorite” might be more appropriate for a personal opinion), but the fans of a traditional ensemble called “The World’s Greatest Jazz Band” would probably disagree—especially since a few members of that band battled the boppers head-to-head on the “Bands for Bonds” radio show. If we narrow the title to “Greatest Modern Jazz Concert”, or even better, “Classic Charlie Parker-Dizzy Gillespie Live Recordings”, we may still have a few dissenters, owing to other recordings issued since the Massey Hall concerts, including the spectacular Town Hall concert of June 22, 1945, where Diz, Bird, Max, Al Haig, and Curly Russell essayed the bop repertoire to a young and enthusiastic audience, or the brilliant March 31. 1951 broadcast where Diz, Bird, Bud, Tommy Potter, and Roy Haynes blew the roof off Birdland with dazzling updates of bop standards.

Still, the Massey Hall concert has its proponents. A persistent rumor of a purported feud between the two hornmen inspired their combative nature, but the recordings show that the sparks flew every time Bird and Diz shared a stage. Gillespie strongly denied any long-standing arguments between himself and Parker, so Bird’s announcement of “Salt Peanuts” as being composed by “my worthy constituent, Dizzy Gillespie” was probably just a little innocent fun. And while Parker and Gillespie were not “trying to blow each other off the stage”, they did engage in playful dialogue through song quotes like “Laura” and “On the Trail”. In his book, “Wail“, biographer Peter Pullman claims that Powell’s unusual comping on “All the Things You Are” might be revenge to Parker and Gillespie for not paying attention to his earlier solos.

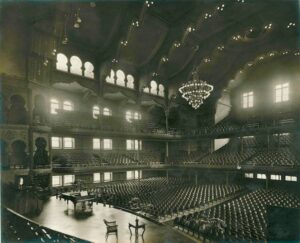

There was some drama early on. According to Chuck Haddix, during the opening set by an all-star Canadian big band, the Massey Hall audience could hear Parker, Gillespie, and the rest of the quintet arguing backstage about who was the bandleader, who would call the tunes, and about their overdue payment. Some of the band members were also peeved at Mingus and Roach for bringing in a state-of-the-art tape recorder, and their plan to release the concert recording on their newly-formed label, Debut. Many of these disagreements were still unresolved when the big band departed and the “Quintet of the Year” took the stage. One can imagine the all-star group’s surprise in seeing the massive three-story auditorium at one-quarter capacity (one photo in the new album’s liner insert shows several rows of empty seats). Foolishly, the concert promoters decided that there was little need to advertise the concert, as the members of the sponsoring group, the New Jazz Society of Toronto, were expected to spread the word themselves. On the other hand, the concert’s primary competition, a postponed rematch between prizefighters Jersey Joe Walcott and Rocky Marciano, was heavily promoted and broadcast on nationwide television in both the US and Canada.

What the audience lacked in numbers was compensated through their enthusiastic response to the music. They cheered and whistled as the quintet started their virtual warmup, “Perdido”, and some clapped on the off-beats during Parker’s opening solo. Dizzy may have been clowning at the same time, for there are several moments of spontaneous laughter while Bird plays. The audience certainly noticed that Parker was not playing his usual horn, but a white plastic alto he used whenever his French Selmer alto was in the pawnshop. Gillespie’s solo opened with an echo of Parker’s final line, and within a chorus, the trumpeter sent high-register motives rocketing off each other. Roach cajoled and encouraged the trumpeter from behind his drum kit, and the ensuing solo by Powell showed that his technique was not impaired despite his recent stay in a mental institution—as well as the prodigious amount of alcohol he had consumed a few hours earlier. Mingus’ bass sound comes in and out during the horn solos, and that was likely a direct result of his attempts to record the gig while playing his bass (more on that later). After Parker’s sarcastic spoken introduction, “Salt Peanuts” tears off at a brisk clip. Contrary to the purple descriptions of this track, Bird’s solo was not played “so fast that many reed players can’t figure out what’s going on”; rather, he played a very logical and highly inspired solo that used the tune’s main riff as building material (and some of this played to the composer’s antic screaming of the tune title!). Gillespie’s solo is both poised and fiery, with an exquisite line in the stratosphere at the solo’s midpoint. Powell gobbles up all the notes he can over the tight rhythmic backing of Mingus and Roach. Max’s solo featured a plethora of great ideas played over a powerful bass drum pulse. “All the Things You Are” was the last number of the concert’s first half, and Powell starts his whole-note accompaniment pattern almost from the initial downbeat. Although Powell does not play the chords the hornmen expect, the only person he throws off is himself, losing track of the song form near the middle of the trumpet solo (at one point, Gillespie tries to remedy the problem by going back to the melody). When it’s his turn to solo, Powell tries to blend bop with this whole-tone style. It doesn’t go very well, and he finally abandons the frilly chords in favor of straight-ahead bebop. Mingus gets his first solo of the night which was captured with good fidelity on the original tape (again, more on this later). The quintet—which had not had a rehearsal or sound check before the concert—then segued into Monk’s “52nd Street Theme” as a signal for the intermission. Mingus was caught off-guard: he was the only member of the group who had not worked regularly in the Manhattan nightclubs where this tune was usually played, and he did not know the head arrangement. The bassist let off his mighty temper backstage while the audience filed out of the theatre.

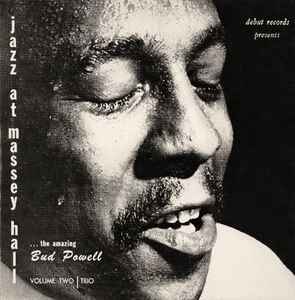

The intermission was significantly extended as the musicians and some of the audience congregated at a bar across the street to watch the boxing match on TV. The main card did not last too long with Marciano knocking out Walcott in the first round. Assuming that the main fight was last on the program, I would guess that it had not yet taken place and the musicians held off the second half to watch some part of the fight. The rhythm section was the first to return to Massey. Roach started the second half with a solo called “Drum Conversation” with the audience showing their enthusiasm through cheers, whistles, and applause. Roach’s fine sense of dynamics was displayed in the solo’s central section which featured an effective diminuendo. The piece continued with impeccably executed high-speed patterns, and another decrease in volume to signal the coda. With Powell and Mingus rejoining Roach onstage, Powell opened with a  Latin-flavored arrangement of “I’ve Got You Under My Skin”. The setting included a mid-chorus break for Powell’s breathtaking unaccompanied runs up and down the keyboard. Powell’s lush chords back a version of “Embraceable You” in walking tempo, and his lovely solo is complimented by Mingus’ lyrical bass solo. Jerome Kern’s “Sure Thing” is an odd cameo, running just over 2 minutes and sounding like an exercise in pseudo-classical frills. The briskly-paced “Cherokee” gets us back to the bop repertoire, with Powell spinning long lines over the insistent beat of Mingus’ walking pattern and Roach’s brushes. Max stays with the brushes and the steady bass drum for an astounding solo displaying both technique and artistry. “Hallelujah” (mis-identified as “Jubilee” on earlier releases) is played slightly slower than “Cherokee” but maintains the same rhythmic background. Powell’s solo is a little more fragmented here, but rests between the phrases accentuate their unique shapes and contours. George Shearing’s “Lullaby of Birdland”, taken at a tempo considerably faster than usual, showcases the great interplay between the three musicians.

Latin-flavored arrangement of “I’ve Got You Under My Skin”. The setting included a mid-chorus break for Powell’s breathtaking unaccompanied runs up and down the keyboard. Powell’s lush chords back a version of “Embraceable You” in walking tempo, and his lovely solo is complimented by Mingus’ lyrical bass solo. Jerome Kern’s “Sure Thing” is an odd cameo, running just over 2 minutes and sounding like an exercise in pseudo-classical frills. The briskly-paced “Cherokee” gets us back to the bop repertoire, with Powell spinning long lines over the insistent beat of Mingus’ walking pattern and Roach’s brushes. Max stays with the brushes and the steady bass drum for an astounding solo displaying both technique and artistry. “Hallelujah” (mis-identified as “Jubilee” on earlier releases) is played slightly slower than “Cherokee” but maintains the same rhythmic background. Powell’s solo is a little more fragmented here, but rests between the phrases accentuate their unique shapes and contours. George Shearing’s “Lullaby of Birdland”, taken at a tempo considerably faster than usual, showcases the great interplay between the three musicians.

Gillespie and Parker returned to the stage for three more quintet numbers. “Wee” (aka “Allen’s Alley”) is a tight and focused performance, with Bird finding new ways to connect his favorite phrases, and Dizzy’s bristling ideas fueled by Roach’s powerful bombs. Powell’s right hand flies over the keys with a matrix of overlapping ideas. Mingus’ bass is missing entirely, leaving Roach’s bass drum to fill the void in the low frequencies. The bass can be heard slightly in the elegant reading of Tadd Dameron’s “Hot House”. Parker plays his best solo of the night, relying on the bass player in his head instead of the human one standing behind him. I love how Parker alternates wailing blues with virtuosic runs. Gillespie is bright and straight-forward. A quote from “Carmen” appears in the same place as it did when Bird & Dizzy played “Hot House” on a TV show the year before (which means that Gillespie was probably using the quote as a fallback device). Powell’s solo is loaded with ideas, and before the track ends, Mingus is back for another solo. We don’t know where he was before, but the bass is beautifully captured on the original tape. “A Night in Tunisia” is the final track, and the quintet is poised for a grand finale. Parker takes the extended break which launches him into a solo full of daring phrases placed against the tune structure. Gillespie’s solo builds in intensity over three choruses, with each phrase contributing to the solo as a whole. Powell is in great form with astonishing speed and flowing ideas. Gillespie’s dramatic cadenza takes the piece out and brings the audience to its feet. The big band returned, and while the quintet was featured on one of its pieces, Mingus did not record any of the band’s performances.

Soon after the concert’s end, the quintet and the promoters met at a local radio station to listen to the tape and complete financial arrangements. The ticket revenue was not sufficient to cover the artist fees, so the producers wrote checks to the musicians from their personal bank accounts. Parker—who had already received an advance—cashed his check at the venue before leaving town, and his check was the only one that cleared. As Gillespie later quipped, the other checks “just bounced and bounced and bounced”. And then there was the tale of the tape. Mingus’ bass had not been recorded properly, and once again, he flew off the handle. However, I suspect that the problems may have been the bassist’s fault. It is very difficult to multi-task live recording with performance. Photos of the concert show that the tape recorder was located right next to Mingus’ bass. Since there was no sound check before the concert, Mingus set levels by guesswork and the horn solos probably threw the level meters into the red zone, where distortion was possible. Every time that happened, Mingus felt compelled to stop playing his bass and readjust the input levels on the recorder (Notice that this did not happen on the trio set, only during horn solos in the quintet sets). In his outrage, Mingus said he planned to erase the tapes. This led to an urgent telegram from concert promoter Dick Wattam to critic Barry Ulanov, stating “Do not let Mingus erase the tapes…He is unbalanced.”

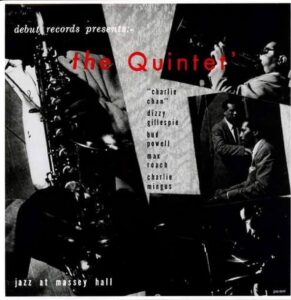

In the end, Mingus did not erase the tapes. In fact, he preserved the original concert tapes as part of a controversial solution. Unable to extract the bass parts from the live recording, he went into a New York recording studio a few months after the concert and overdubbed new bass lines on top of the old ones! With the technology that existed at that time, the only way to accomplish this task was to play the live tape into a sound mixer with one output going to a second tape machine and the other going to Mingus’ headphones in the studio. With the simultaneous start of the recording and playback tape decks, Mingus simply his bass parts onto the new tape. He also decided to be clever, playing new responses to his still-audible live tracks, or reacting—months after the fact—to lines played by the other musicians. We don’t have any specifics about this doctoring session, but we do know that Mingus offered the recording to Norman Granz for a ridiculously high fee (possibly as much as $100,000). Granz refused the offer, but did he pay for the extra session to see if the recording could be salvaged? We don’t know, but starting with the 12″ Debut LP of the Massey Hall concert, the overdubbed bass lines were usually there, whether the listener wanted them or not. As Parker was under an exclusive recording contract with Granz, the saxophonist used one of his favorite pseudonyms on the Debut album cover: Charlie Chan.

ridiculously high fee (possibly as much as $100,000). Granz refused the offer, but did he pay for the extra session to see if the recording could be salvaged? We don’t know, but starting with the 12″ Debut LP of the Massey Hall concert, the overdubbed bass lines were usually there, whether the listener wanted them or not. As Parker was under an exclusive recording contract with Granz, the saxophonist used one of his favorite pseudonyms on the Debut album cover: Charlie Chan.

The new Craft reissue is now a definitive edition, precisely because of the overdubbed bass lines. Disc one offers the complete original concert tape (which is what I used for this review). The bass is intermittent, but remnants are still there. Disc two presents the concert with Mingus’ overdubs. It may be that the crude method of overdubbing led to speed differences between the live and doctored recordings. The track timings do not line up, but that could be due to applause or spoken announcements. Current technology (actually, it’s been around for several decades now) would allow an engineer to synch the two tapes, and feed them as separate channels to a stereo disc. Most CD players and/or amplifiers have switches to play the left or right channels into both speakers. This control would allow the listener to jump between the original and doctored recordings with the flip of a switch (just like you would switch between a DVD’s movie soundtrack and the commentary track). And of course, it’s no big deal if you didn’t have that switch: Mingus’ overdubs would just appear on one stereo channel instead of both. So, tell your sons and daughters (and grandkids, too) to look for a digital reissue of this concert many years from now with a synchronized version of the two Massey Hall tapes. At last, modern technology will serve the music it preserves.