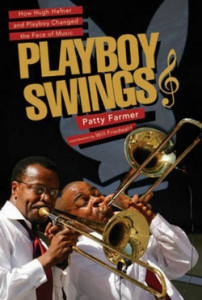

Men of the 1950s who wanted to live a swinging bachelor lifestyle could turn to Playboy magazine and its editor and founder Hugh Hefner for an idealized formula: We like our apartment. We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion of Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex. Although the preceding description appeared in the first issue of Playboy in November 1953, Hefner took several years to learn some of these skills himself. However, jazz was one of Hefner’s existing passions and as Playboy grew in popularity and stature, Hefner used the magazine to promote the music to a large audience. “Playboy Swings” (Beaufort Books) by Patty Farmer “with contributions by Will Friedwald” traces the history of Hefner’s ventures into the worlds of music and entertainment, with lengthy discussions of the magazine’s jazz articles, the all-star jazz polls, jazz festivals (both the initial event from Chicago in 1959 and the ongoing Hollywood Bowl fests), Hefner’s two music-oriented television series, and the Playboy clubs.

Men of the 1950s who wanted to live a swinging bachelor lifestyle could turn to Playboy magazine and its editor and founder Hugh Hefner for an idealized formula: We like our apartment. We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion of Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex. Although the preceding description appeared in the first issue of Playboy in November 1953, Hefner took several years to learn some of these skills himself. However, jazz was one of Hefner’s existing passions and as Playboy grew in popularity and stature, Hefner used the magazine to promote the music to a large audience. “Playboy Swings” (Beaufort Books) by Patty Farmer “with contributions by Will Friedwald” traces the history of Hefner’s ventures into the worlds of music and entertainment, with lengthy discussions of the magazine’s jazz articles, the all-star jazz polls, jazz festivals (both the initial event from Chicago in 1959 and the ongoing Hollywood Bowl fests), Hefner’s two music-oriented television series, and the Playboy clubs.

This book will not change the opinions of those who disapprove of Hefner and the Playboy lifestyle. It is straight out of the Playboy publicity machine: Hefner and his cohorts Al Podell, A.C. Spectorsky and Victor Lownes are all portrayed as earnest fellows trying to build a singular image under the Playboy name—and supposedly all dating Playmates at the same time. The book follows the magazine’s disturbing tendency to discuss a woman’s physical attributes before talking about her other accomplishments (for example, Lainie Kazan was the first woman to operate and manage a Playboy club, but she is introduced with a discussion of a nude pictorial she did for the magazine years earlier). While there is no doubt of Hefner’s sincere love of jazz, the many controversies that emerged around him are hardly discussed. Bill Cosby, who had a long professional relationship with Playboy, is also here, with no mention of the sexual abuse allegations—one reportedly with a Playboy bunny—that have tarnished his image.

Playboy and Hefner tightly wound the worlds of sex, jazz, sports cars, gourmet food, fine wine and bachelor pads, but if we concentrate on the music alone, it’s clear that Hefner gave the music significant and important exposure through a wide range of venues. Sure, “The 1958 Playboy Jazz All-Stars” double LP had song titles like “Cat Without a Playmate” and the notes contained a leering comparison of a Lionel Hampton track to a recent centerfold, but the music was excellent and it was presented with personnel and discographies for each artist. The 1959 3-disc set included live tracks from the initial Playboy Jazz Festival in Chicago—most of which have not been issued elsewhere. That festival boasted a tremendous roster of talent, including Count Basie, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Stan Kenton, and Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. Hefner wanted Frank Sinatra to sing at the festival, but when he couldn’t attend, Hefner hired a top-notch Sinatra imitator, Duke Hazlett—and many of the audience members seemed unaware that it wasn’t really Sinatra singing with the Basie band! Hefner’s first television series, the syndicated 1959-61 show “Playboy’s Penthouse” had an impressive list of jazz and pop singers including Sarah Vaughan, Joe Williams, Cy Coleman, and Mabel Mercer. Hefner’s later series “Playboy After Dark” aired during the late 1960s, and while there were rock and blues bands featured on that series, there were still appearances by Buddy Rich, the Modern Jazz Quartet, and Tony Bennett (the excellent Bennett tribute show is discussed in the book, but somehow both Farmer and Friedwald missed the identity of Bennett’s companion for the show: Lindsay Wagner, later “The Bionic Woman”!)

The discussions of Playboy’s jazz polls, festivals and television shows take up the first section of the book, and are quite informative. However, the narrative bogs down as it moves into the history of the Playboy clubs. The clubs were an important extension of the Playboy name and lifestyle, but the endless details about non-music activities makes the book lose its focus. How many times do we need to hear about the endless rules and rigorous training that the bunnies endured? Was it absolutely necessary to recount a highly questionable anecdote about the sexual liaisons between Playboy bunnies, Al Jarreau and his accompanist? And if this book is supposed to be about music that swings, why are there extensive interviews with Rich Little, Jerry Van Dyke, Mitzi Gaynor, Larry Storch, Trini Lopez and Lorna Luft? The answer to the above questions is that “Playboy Swings” is actually a reworking of Farmer’s unpublished history of the clubs, “Playboy on Stage”. That book had numerous editorial problems, and many of those issues have been carried over into the new book. The editing on the new book is simply dreadful. One section of text regarding the Playboy Jazz All-Stars LPs appears word-for-word in two consecutive chapters. While each club is discussed in its own chapter, the anecdotes related by celebrities do not always correspond to the club under examination. To cite just one of the many examples in this book, there is an interview with Joan Rivers within the chapter on the Miami Playboy club which refers to her appearances at the Lake Geneva resort—a property which is not discussed again for another 140 pages. We read casual mentions of Mort Sahl’s marriage to Playmate China Lee by two different witnesses within three pages. The ubiquitous “bunny dip” (the unique way that the bunnies served drinks and exchanged ashtrays) comes up every few pages—always in quotes and usually with some sort of explanation. The sheer repetition of information makes me suspect that no one took the time to read this manuscript with red pencil firmly in hand.

What makes this scenario tragic is that a narrative of Hefner’s role in promoting jazz is long overdue, and it is doubtful that anyone outside of the Playboy empire would attempt to document it. There is a considerable amount of good information within “Playboy Swings” but one must wade through endless anecdotes, an obtrusive and chatty writing style, and innumerable puns. With solid editing and a substantial rewrite, this book could be an important historical volume. As it is, “Playboy Swings” is just an unholy mess.