Between 1926 and 1939, Thomas “Fats” Waller recorded 73 sides on pipe organs at the Victor studio in Camden, New Jersey and at St. George’s Hall and the HMV Abbey Road studio in London. Waller was the first musician to record jazz on the pipe organ, and part of the success of the recordings is how Waller tamed the huge instrument and gave it its own unique swing.

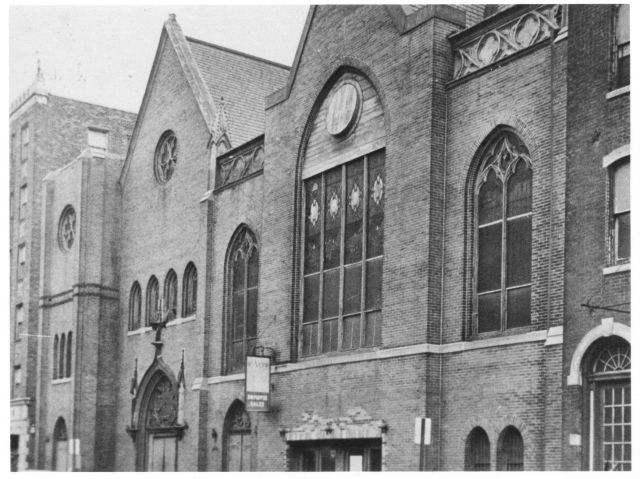

Before discussing the recordings, there are a number of questions regarding the Victor sessions, and some of them must be worked out by educated suppositions. In 1918, Victor purchased the Trinity Baptist Church in Camden, New Jersey (left) with the intent of building a “recording laboratory”. The building was at least 50 years old, and the existing pipe organ was in need of restoration and improvements. In 1921, Victor hired the Estey Pipe Organ Company to redesign the instrument for recording, including several features usually found solely on theatre organs. Fortunately for historians, Estey assigned opus numbers to its organs, and each revision to the instrument led to an additional opus number being issued—as a result we also know that the Estey in Camden had three major revisions between 1921 and 1926.

Before discussing the recordings, there are a number of questions regarding the Victor sessions, and some of them must be worked out by educated suppositions. In 1918, Victor purchased the Trinity Baptist Church in Camden, New Jersey (left) with the intent of building a “recording laboratory”. The building was at least 50 years old, and the existing pipe organ was in need of restoration and improvements. In 1921, Victor hired the Estey Pipe Organ Company to redesign the instrument for recording, including several features usually found solely on theatre organs. Fortunately for historians, Estey assigned opus numbers to its organs, and each revision to the instrument led to an additional opus number being issued—as a result we also know that the Estey in Camden had three major revisions between 1921 and 1926.

It’s important to note that the organ was designed for recording and not for church services. Had it been a church organ, the console and pipes would have been in the same room. Instead, the pipes were placed in a separate room, which was presumably sealed off so that outside noises would not affect the recordings. Compounding the problem was the organ’s inherent delay between the pressing of the key and the sound being produced by the pipes. Thus, the organist at the console would only hear a muffled and delayed version of what he was playing. What made recording at Trinity even more challenging was that the cutting turntables were located on an upper floor because the speed of the turntable motors were controlled with weights instead of electricity (AC power was considered too unreliable at the time) and the weights required several feet of dropping room so that they would continue running for the duration of the recording.

So, with all these obstacles in place, just how did they record the Estey at Camden? First of all, we know that the Victor engineers were unable to  make any satisfactory recordings of the pipe organ (right, in the only existing photo) using the old acoustic recording method. Yet, acoustic recording’s successor, electrical recording, opened up a number of possible solutions. With the Estey on the ground floor, the cutting tables upstairs, and the pipes in some other room, a monitoring system must have been set up so that the organist could hear what he was playing. We know that a buzzer had been set up between the Estey and the recording booth to inform the organist that recording had begun—it can be heard on several Victor 78s of the period. Therefore, it’s not beyond reason that a rudimentary speaker or headphone system may have been set up for the organist to monitor his own playing. In order to sync the other instruments to the delayed beat of the organ, my educated guess is that those musicians would perform in the pipe room. I stand by this theory despite the quotes of Garvin Bushell, who played on the Louisiana Sugar Babes session with Waller. Bushell claimed that “the organ pipes were in one room and we were in another” and also stated that during recording, Waller was in a room “about a city block away” from the rest of the musicians. This would indicate a total of three rooms: one for Waller and the console, another for the remaining musicians, plus the organ pipe room. The synchronization issues in such a scenario would have been a nightmare, even with a monitoring system!

make any satisfactory recordings of the pipe organ (right, in the only existing photo) using the old acoustic recording method. Yet, acoustic recording’s successor, electrical recording, opened up a number of possible solutions. With the Estey on the ground floor, the cutting tables upstairs, and the pipes in some other room, a monitoring system must have been set up so that the organist could hear what he was playing. We know that a buzzer had been set up between the Estey and the recording booth to inform the organist that recording had begun—it can be heard on several Victor 78s of the period. Therefore, it’s not beyond reason that a rudimentary speaker or headphone system may have been set up for the organist to monitor his own playing. In order to sync the other instruments to the delayed beat of the organ, my educated guess is that those musicians would perform in the pipe room. I stand by this theory despite the quotes of Garvin Bushell, who played on the Louisiana Sugar Babes session with Waller. Bushell claimed that “the organ pipes were in one room and we were in another” and also stated that during recording, Waller was in a room “about a city block away” from the rest of the musicians. This would indicate a total of three rooms: one for Waller and the console, another for the remaining musicians, plus the organ pipe room. The synchronization issues in such a scenario would have been a nightmare, even with a monitoring system!

Then there’s the whole issue of playing jazz on the pipe organ. As a boy, Fats Waller had played the organ at Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, and later worked as the house organist at the Lafayette Theatre. He’d undoubtedly experimented with making the organ swing. By 1926, Ralph Peer—who had supervised Waller’s first piano solo recordings—was the recording supervisor for Victor’s “race records” department (read: Black music) and he was anxious to sign Waller to Victor. That Waller’s first recordings for Victor were organ solos was hardly a coincidence. Just two weeks before his Victor debut, Waller played a reed organ on Fletcher Henderson’s Columbia recording of “The Chant”. Even though Waller’s contribution was rather small, it was his first recording on the organ, and that might have spurred his thoughts to recording on the newly-restored Estey at Camden. Indeed, recording on the Estey may have been the final negotiating point leading to Waller’s long association with Victor.

Yet, Peer couldn’t have simply brought in Waller for a jazz organ date without raising a few eyebrows at Victor (after all, this was uncharted territory). The discographies tell us that on November 17, 1926, Waller, as part of the “Six Hot Babies” recorded four attempts at “All God’s Children Got Wings”, and none of the takes were issued or survived. Was this recording of an old spiritual a cover for Peer’s actual intention—to record Waller’s first pipe organ solos? Rather than proposing jazz organ to his superiors at Victor, Peer could well have decided to try the spiritual first, then record Waller’s organ solos “to salvage the date”, then let the recorded results determine whether to continue with further jazz organ recordings. Whatever the intention, Waller’s mastery came through on the records and he recorded another 8 sessions on the Estey pipe organ before the Camden studios were closed in 1935.

It’s not easy to make a pipe organ swing. When an organ key is touched, air is forced through a pipe, and the amount of pressure the organist places on the key does not alter the velocity of the air. Further, the organ does not have a percussive element like the piano, where strings are struck with a felt hammer. However, the amount of time that the organ key is depressed alters the sound, and Waller found that the combination of a light staccato touch on the keyboard and short, accurate pedal bass notes could give the pipe organ an elegant swing. What attracted Waller to the organ is the amount of color he could produce through various organ stops (and their combinations, known as registrations). The organs on which he recorded also had a theatre organ feature called “second touch” which allowed him to engage an additional set of pipes playing the same pitches by pushing further on the keys. Waller learned most of this by experimentation, and as each pipe organ had its own characteristics, it took awhile for Waller to find a way to coax jazz out of the instrument.

At the first Camden session, Waller recorded two takes of “St. Louis Blues” and a single take of his original “Lenox Avenue Blues”. On “St. Louis Blues”, Waller uses the 16-bar tango section (Saint Louis woman, with her diamond rings) as a framing device for the 12-bar main melody (I hate to see the evening sun go down). The tango section opens both takes, followed by two choruses of the melody and another rendition of the tango before moving into his improvisation on the 12-bar form. Waller was already learning the sounds of the Estey, and he effectively sets off contrasting lines with alternating registrations. “Lenox Avenue”, which despite its title is not a blues, finds Waller experimenting with the volume pedal and offering several variations on one of his favorite piano licks. What’s missing from both of these performances is the swing. The rhythmic feel is rather stodgy and the notes of the pedal and left hand seem too legato to create swing. Still, as noted, the recordings showed promise and reason enough to continue experimenting.

At the first Camden session, Waller recorded two takes of “St. Louis Blues” and a single take of his original “Lenox Avenue Blues”. On “St. Louis Blues”, Waller uses the 16-bar tango section (Saint Louis woman, with her diamond rings) as a framing device for the 12-bar main melody (I hate to see the evening sun go down). The tango section opens both takes, followed by two choruses of the melody and another rendition of the tango before moving into his improvisation on the 12-bar form. Waller was already learning the sounds of the Estey, and he effectively sets off contrasting lines with alternating registrations. “Lenox Avenue”, which despite its title is not a blues, finds Waller experimenting with the volume pedal and offering several variations on one of his favorite piano licks. What’s missing from both of these performances is the swing. The rhythmic feel is rather stodgy and the notes of the pedal and left hand seem too legato to create swing. Still, as noted, the recordings showed promise and reason enough to continue experimenting.

From the first notes of the first tune Waller recorded on January 14, 1927, there’s a new feel to the Estey. “Soothin’ Syrup Stomp”, the first of five solos recorded that day, displays a multi-strain compositional form, an excellent—if rather slippery—tempo and a light buoyant feel to the rhythm. Waller’s tempo holds better on the master take, and except for a couple finger fumbles, it is the stronger performance. The organ heaves and sighs on the alternate take of the medium-slow blues “Sloppy Water”, but the slightly brighter tempo of the master take lessens that effect and heightens the overall swing. Waller returns to the music of W.C. Handy with a single take of “Loveless Love”. The left hand and pedal patterns are wondrously varied on this recording, as are Waller’s choice of right hand registrations. Both “Messin’ Around With The Blues” and “Rusty Pail” have intricate formal schemes that mix 12-bar blues choruses with 16- and 32-bar song forms, and each uses recurring melodic material to tie the various parts together. Since Waller was playing solo, he had the flexibility to change his musical forms at will, and the two existing takes of “Rusty Pail” show a key variation in the order of blues and song form choruses.

Waller was back in Camden on February 16 for a short session that yielded two takes each of two originals, “Stompin’ The Bug” and “Hog-Maw Stomp”. “Stompin’” finds Waller alternating his bass patterns in the style of his mentor, James P. Johnson. The rhythmic feel on the alternate is more strut than the swing of the master take, and if Waller’s swing is still not consistent, it represents a large leap forward from the November, 1926 session. “Hog-Maw” is a joyous romp with many of Waller’s best organ style traits making an appearance (subtle dynamic variations with the pedal, effective use of the registration, and Waller’s best organ swing to date), along with a surprising break on the organ’s percussion deck. There is also evidence that the Victor engineers were still experimenting with optimum microphone placement, as there is noticeably more presence to the organ sound on the master take than on the alternate.

On the May 20, 1927 session, Victor decided to make another attempt at recording Waller and the pipe organ with other musicians (The first attempt was, of course, the rejected spiritual at the initial Waller session). On the first part of the session, Waller teamed with vocalist Alberta Hunter (right) on three songs, “Sugar”, “Beale Street Blues” and “I’m Going To See My Ma.” Each tune was recorded as a pipe organ solo and as a vocal/organ duet; however, the solo version of “I’m Going To See My Ma” was never released and is now considered lost. The solo and vocal versions of “Sugar” are in different keys and the placement of the verse is changed from the opening section (solo version) to the reprise (vocal version). It is rather surprising to hear Waller doubling Hunter’s line on the vocal take—I can’t imagine Hunter needed it—but the singer obviously appreciated the solo chorus of her accompanist as witnessed by her vocal aside, “Honk that thing, Fats!”. On “Beale Street Blues”, another spoken aside is Hunter’s only appearance for the first 2 ¼ minutes, then she sings the final two choruses of the song. Waller gets a very legato sound from the organ on this take and there is a mighty chorus on the organ pedals right before Hunter’s entrance. The solo version is in a brighter tempo and it swings elegantly throughout. The pedal chorus moves to the end of the performance, and it is beautifully recorded by the Victor engineers. “I’m Going To See My Ma” is not much of a song (one could imagine Waller parodying it with his Rhythm a decade later), but Waller and Hunter create a decent, if rather uninspired, version. Waller takes most of the first two minutes of the recording, but comes up with little other than a few registration variations. Hunter plays with the rhythm of the song in her chorus and Waller finishes the arrangement with a short coda.

tune was recorded as a pipe organ solo and as a vocal/organ duet; however, the solo version of “I’m Going To See My Ma” was never released and is now considered lost. The solo and vocal versions of “Sugar” are in different keys and the placement of the verse is changed from the opening section (solo version) to the reprise (vocal version). It is rather surprising to hear Waller doubling Hunter’s line on the vocal take—I can’t imagine Hunter needed it—but the singer obviously appreciated the solo chorus of her accompanist as witnessed by her vocal aside, “Honk that thing, Fats!”. On “Beale Street Blues”, another spoken aside is Hunter’s only appearance for the first 2 ¼ minutes, then she sings the final two choruses of the song. Waller gets a very legato sound from the organ on this take and there is a mighty chorus on the organ pedals right before Hunter’s entrance. The solo version is in a brighter tempo and it swings elegantly throughout. The pedal chorus moves to the end of the performance, and it is beautifully recorded by the Victor engineers. “I’m Going To See My Ma” is not much of a song (one could imagine Waller parodying it with his Rhythm a decade later), but Waller and Hunter create a decent, if rather uninspired, version. Waller takes most of the first two minutes of the recording, but comes up with little other than a few registration variations. Hunter plays with the rhythm of the song in her chorus and Waller finishes the arrangement with a short coda.

The greater challenge for the Victor engineers came after Hunter left the studio and Thomas Morris’ Hot Babies entered. This group with Morris on cornet, Charlie Irvis on trombone, Victor’s A&R man Eddie King on percussion and Waller on organ and piano must have been a logistical nightmare to record. Estey had upgraded the organ with an additional console so that the same musician could switch between the organ and Camden’s concert grand Steinway. However, we know that the console did not reach into the pipe room. With Waller playing piano, the engineers had to have an additional microphone by the organ and piano, plus the usual microphones in the pipe room. Whether the other musicians were set up in the pipe room or with Waller (again, using some sort of rudimentary monitoring system), we may never know. None of the instruments sound distant in the recording and somehow, two takes each of three tunes were recorded during the session.

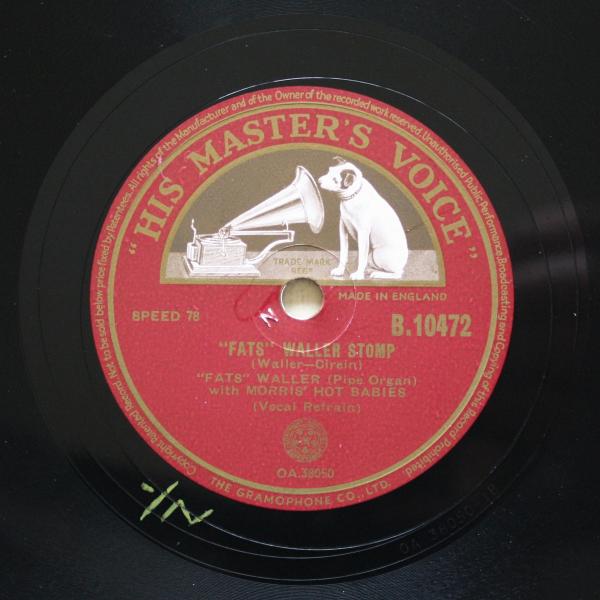

“Fats Waller Stomp” was the first song title to use Waller’s nickname, and the organist gives this recording its rhythmic impetus. Most of the first half is given to alternating ensemble episodes and solo breaks, but then all but King take full-fledged solos. Waller stays on organ throughout and  his accompaniment is a delight. The pedal bass keeps the band together and Waller does his best to swing the band along. He holds a long note in the treble and plays dancing bass notes in the pedal under Morris’ solo, then Waller and King play sharp off-beat accents under Irvis. On both takes, Waller starts his solo with the same held high note, but from there, each solo takes its own direction. The ensemble choruses on “Savannah Blues” are dense and a little ragged on the first take (oddly chosen as the master). Waller changes registration and moves to the upper part of the keyboard on the second take and that seems to help overall. Waller also gets a piano solo on both takes, accompanied by King’s off-beat accents. Waller switches back to organ immediately and the off-beat accents continue under both horn solos. The tempo really drags during the final ensemble on both takes and it’s too bad that Peer didn’t ask for another try. On “Won’t You Take Me Home?” we can hear that Morris and Irvis were a well-matched team. While neither was particularly adept at swinging, their tones were similar, they were good in mutes and both could growl well. For the most part, Waller and King also played well together as a rhythm team (the beat does gets turned around during the organ solo on the master take), and if the constant off-beat accompaniment gets tiring, it should be remembered that many musicians (including Waller) were still learning the rhythmic lessons of Louis Armstrong.

his accompaniment is a delight. The pedal bass keeps the band together and Waller does his best to swing the band along. He holds a long note in the treble and plays dancing bass notes in the pedal under Morris’ solo, then Waller and King play sharp off-beat accents under Irvis. On both takes, Waller starts his solo with the same held high note, but from there, each solo takes its own direction. The ensemble choruses on “Savannah Blues” are dense and a little ragged on the first take (oddly chosen as the master). Waller changes registration and moves to the upper part of the keyboard on the second take and that seems to help overall. Waller also gets a piano solo on both takes, accompanied by King’s off-beat accents. Waller switches back to organ immediately and the off-beat accents continue under both horn solos. The tempo really drags during the final ensemble on both takes and it’s too bad that Peer didn’t ask for another try. On “Won’t You Take Me Home?” we can hear that Morris and Irvis were a well-matched team. While neither was particularly adept at swinging, their tones were similar, they were good in mutes and both could growl well. For the most part, Waller and King also played well together as a rhythm team (the beat does gets turned around during the organ solo on the master take), and if the constant off-beat accompaniment gets tiring, it should be remembered that many musicians (including Waller) were still learning the rhythmic lessons of Louis Armstrong.

Between the Thomas Morris sessions of May and December, Waller played organ on two recordings made as a memorial to Florence Mills. However, these performances by Juanita Stinette Chappelle and Carroll C. Tate have absolutely no jazz content and are not discussed here, nor included in the playlist.

Morris, King and Waller were back in Camden on December 1, 1927, with  Jimmy Archey replacing Irvis and guitarist Bobbie Lecan added to the ensemble. It sounds like Lecan provides all of the accompaniment on the opening choruses of the master take of “He’s Gone Away” (if Waller is present, he is only playing organ pedals). Waller is definitely playing the full organ on the alternate and the tempo seems to drag again. Waller’s piano solo holds the tempo better than any other spot on the recording, and Lecan’s guitar adds needed instrumental color to the group. Archey is the weakest player of the lot and he doesn’t seem to fit in with the rhythmic style of his fellow band members. Morris’ playing on this track relies less on effects and more on melodic statements. Still for some reason, the band only played this one number before taking an extended break to allow Waller to record two solo organ pieces. (There could be any number of reasons for this unusual break in the band’s recordings. My guess is that the issue was technical again: not only was the band not staying together, the next song the band recorded featured vocals by Waller and one of the other members of the group. Thus, there were more technical obstacles to overcome.)

Jimmy Archey replacing Irvis and guitarist Bobbie Lecan added to the ensemble. It sounds like Lecan provides all of the accompaniment on the opening choruses of the master take of “He’s Gone Away” (if Waller is present, he is only playing organ pedals). Waller is definitely playing the full organ on the alternate and the tempo seems to drag again. Waller’s piano solo holds the tempo better than any other spot on the recording, and Lecan’s guitar adds needed instrumental color to the group. Archey is the weakest player of the lot and he doesn’t seem to fit in with the rhythmic style of his fellow band members. Morris’ playing on this track relies less on effects and more on melodic statements. Still for some reason, the band only played this one number before taking an extended break to allow Waller to record two solo organ pieces. (There could be any number of reasons for this unusual break in the band’s recordings. My guess is that the issue was technical again: not only was the band not staying together, the next song the band recorded featured vocals by Waller and one of the other members of the group. Thus, there were more technical obstacles to overcome.)

The first solo, “I Ain’t Got Nobody” was a song that Waller returned to nearly a decade later at a solo piano session. As on the solo version of “Sugar”, Waller starts with 8 bars of the song and then moves directly to the verse. Once he returns to the chorus, he plays the melody with tenderness, but spices things up with witty dotted eighth/sixteenth note asides. He picks up the tempo for the second chorus and offers a rhythmic variation on the melody in lieu of an actual improvisation. Both takes of “The Digah’s Stomp” seem to drag through rhythmic mud. Waller holds the tempo throughout, but the alternate is a bore and the master only comes to life in the final two choruses. Unlike the earlier compositions Waller played on the pipe organ, “Digah” relies more on riffs than on typical keyboard patterns. The riff patterns simulate a big band in the final chorus, and on the master take, Waller sets up the finale with a fine chorus played pianissimo.

When the band reassembled, they recorded another three songs, “Red Hot Dan”, “Geechee” and “Please Take Me Out Of Jail”. “Red Hot Dan” has the first recorded Waller vocal, but close listening reveals that another musician sings responses to Waller’s scat. Overall, the band seems to play better together. Even Archey appears to have better rhythmic control than before. They hold tempo better on the organ passages, and on the master take of “Geechee”, there is a marvelous ensemble passage where the rhythm is tight and clean. “Geechee” also features delightful organ breaks and superbly executed piano solos in both takes. The angular melody and complex arrangement of “Please Take Me Out Of Jail” presented some problems for the band, and the alternate take is quite ragged. The master take shows the benefit of a little woodshedding and rehearsal. Here, they nail the ensemble parts, and Morris and Archey play a stunning double break near the end. For his part, Waller’s opening organ solo swings especially well, and there’s hardly a difference in the swing when he switches over to piano midway through the recording.

In 1928, Waller and James P. Johnson collaborated on the Broadway show, “Keep Shufflin’”. In addition to writing songs for the score, the two played in the pit orchestra and entertained the audience during the intermissions with improvised 2-piano duets. Peer brought Johnson, Waller, and two soloists from the orchestra, cornetist Jabbo Smith and reedman Garvin Bushell, to Camden to record music from the show. The Camden studio had only one piano, so Johnson played it and Waller moved to the organ. The recordings were billed as the “Louisiana Sugar Babes” (no one knows where they got the title) and with its unusual instrumentation (with Bushell doubling bassoon in several spots), it was the prototype of jazz groups with odd instrumental combinations led by Red Norvo (1933), Edmond Hall (1941) & Jimmy Giuffre (1958).

Two things are evident from the outset of this session: first, all of the sidemen are more advanced in instrumental technique and swing than the Tom Morris group, and second, the ensemble swing of the Sugar Babes is grounded in Johnson’s stride piano rather than Waller’s organ pedals. Waller uses the Estey as a color instrument throughout the session and his countermelodies behind the soloists are delightful and inventive. Jabbo Smith was Louis Armstrong’s only real competition at the time, and Garvin Bushell had distinct tone qualities on each of his reed instruments: clarinet, alto sax and bassoon. The graceful melody of “Willow Tree” is passed around the band, with most of the solo spots being elaborations of the tune rather than full-fledged improvisations. Waller’s inventive use of registration helps smooth over the edges of the many changes in instrumental color. On its master take, “’Sippi”  has a lovely rendition of the melody by Smith (with superb accompaniment from Waller), followed by Bushell playing the first jazz bassoon solo on record. Bushell gets the double reed instrument to swing rather well, and the counterpoint behind him by Johnson and Waller is quite fascinating. On the alternate, Johnson joins in on the accompaniment of Smith’s melody statement and Waller lays out behind Bushell. Once the songs from “Keep Shufflin’” had been recorded, the group moved on to two popular songs of the day, “Thou Swell” and “Persian Rug”. The two takes of the Rodgers and Hart standard are sheer delight, with fine solos by Waller and Bushell, a extraordinary duet by Smith and Johnson, and a powerfully swinging final chorus. Only a few cases of tempo rushing on the alternate separates it from the master in terms of quality. Waller has a little fun with the pseudo-Middle Eastern theme of “Persian Rug”, using exotic sounding registrations throughout. He also provides a dancing counterpoint to Bushell’s bassoon solo, and the organ/piano duet that closes the side displays a remarkable similarity of tone between the two instruments.

has a lovely rendition of the melody by Smith (with superb accompaniment from Waller), followed by Bushell playing the first jazz bassoon solo on record. Bushell gets the double reed instrument to swing rather well, and the counterpoint behind him by Johnson and Waller is quite fascinating. On the alternate, Johnson joins in on the accompaniment of Smith’s melody statement and Waller lays out behind Bushell. Once the songs from “Keep Shufflin’” had been recorded, the group moved on to two popular songs of the day, “Thou Swell” and “Persian Rug”. The two takes of the Rodgers and Hart standard are sheer delight, with fine solos by Waller and Bushell, a extraordinary duet by Smith and Johnson, and a powerfully swinging final chorus. Only a few cases of tempo rushing on the alternate separates it from the master in terms of quality. Waller has a little fun with the pseudo-Middle Eastern theme of “Persian Rug”, using exotic sounding registrations throughout. He also provides a dancing counterpoint to Bushell’s bassoon solo, and the organ/piano duet that closes the side displays a remarkable similarity of tone between the two instruments.

It would be 17 months before Waller recorded again on the Estey. Waller may have been incarcerated for some of that time (there were continuing issues with alimony payments to his first wife), and when he returned to Camden on March 1 and August 2, 1929, he recorded only on piano in solo and band settings. Two of the songs recorded as pipe organ solos on August 29 were also made as piano solos, and the pipe organ versions remained unissued until the 1970s. Only one organ solo from this session was released on 78, and as it was the last organ solo that Waller recorded for Victor, the title, “That’s All”, was strangely prophetic. Waller uses the volume pedal to extremes on both takes of “Waiting At The End Of The Road” and the closing choruses (the only ones that really swing) feature a rhythmic variation on the theme (much like “I Ain’t Got Nobody”). “Baby, Oh Where Can You Be?” is better overall, with an attractive rhythmic feel that swings and struts (is this how Erroll Garner would have sounded playing a pipe organ?), and an effective pianissimo section on the first take. Waller uses different registrations on the second take, but the first take’s choices sound better to my ears; however, there are moments on take 2 that out-swing the first. “Tanglefoot” was not recorded as a piano solo, and the two organ takes represent Waller’s only recording of the song. Waller swings well, but sticks close to the melody throughout, and the recordings are not very memorable. “That’s All” seems to sum up all that Waller had learned about making the Estey swing. His varied bass patterns all provide elements of the elegant swing he had recorded in his earlier sides, and there are effective dynamic contrasts, sparking registration choices, and even a few well-executed blue notes.

The Camden studios were closed in late 1935 to make way for the city’s newly expanded subway system. Such a project was probably planned a year or so in advance, and with the Estey soon to be retired, Waller made a final recording at Camden on January 5, 1935. Seven months earlier, Waller had launched the “Fats Waller and His Rhythm” sides, and so he brought the sextet along for the session. Whether the Victor engineers had found new solutions for recording the Estey with other instruments is hard to say, but the discographies indicate that the two sides with organ and “the Rhythm” were recorded in one take each. It was a long day, including a train trip from New York to Camden, and with the help of Waller’s supply of alcohol, the group was feeling no pain by the time they arrived at the studio. There was also a technical problem that came up early in the session, and Victor treated the band to an extended lunch while the glitches were fixed. With a full rhythm section in place, Waller barely uses the organ pedals, and the Estey is essentially a color instrument. Waller may have experimented with Hammond organs by this time, and most of the registrations sound like the ones he would use a few years later after moving exclusively to the electronic instrument. “Night Wind” features a full-chorus organ solo at the outset. While the melody predominates, Waller plays a fine variation in the final eight bars. Waller sings the melody more-or-less straight, with obbligatos by tenor saxophonist Gene Sedric and trumpeter Bill Coleman. “I Believe In Miracles” is a sweet little song with a bouncy rhythm and delicate lyrics. Waller makes the occasional jump into parody during his vocal chorus. Sedric (now on clarinet) plays the melody along with Waller in the opening chorus, and Coleman plays a lovely countermelody behind the vocal, before taking the lead in the final chorus.

Waller toured Europe in 1933, 1938 and 1939, and on the last two of these trips, he was invited to record on the Compton theatre organ (left) at London’s Abbey Road studio. On the first session, August 21, 1938, Waller recorded six tunes with “his Continental Rhythm”, a band made up of local musicians (For many years, American jazz artists appearing in the UK had to appear as solo “variety artists” to comply with rules of the British musician’s union). Waller was always the star of his own recordings, so the British sidemen—while not of the caliber of American jazz musicians—were suitable for these sessions. “Don’t Try Your Jive On Me” and two takes of the Waller anthem “Ain’t Misbehavin’” were recorded with the organ before Waller moved to the piano. “Jive” is a forgettable piece of pop tripe and Waller provides a serviceable performance with a full chorus of organ at the start of the recording and a listless vocal. There aren’t many registration changes, but Waller’s organ style retains much of his piano style including a smoothed-out 4/4 swing pattern in the left hand and wry, extended trills in the right. Near the end of the side, Waller tries to rally the band with a few vocal exhortations, but it’s clear that the band was as bored by this song as Waller. “Ain’t Misbehavin’” fares better. At first listen, the first take seems much too slow, but Waller’s sly counterpoint and sinuous melodic variations during his opening solo chorus makes the tempo seem absolutely right. The second take was chosen as the master, and the tempo is noticeably faster and fine on its own terms. In the last eight of his solo chorus here, he bounces the melodic variations between the organ’s three manuals with different registrations used for each. Waller must have sang this song a few thousand times during his career, but he still found fresh ways to sing the lines and to back them up on the keyboard.

Waller toured Europe in 1933, 1938 and 1939, and on the last two of these trips, he was invited to record on the Compton theatre organ (left) at London’s Abbey Road studio. On the first session, August 21, 1938, Waller recorded six tunes with “his Continental Rhythm”, a band made up of local musicians (For many years, American jazz artists appearing in the UK had to appear as solo “variety artists” to comply with rules of the British musician’s union). Waller was always the star of his own recordings, so the British sidemen—while not of the caliber of American jazz musicians—were suitable for these sessions. “Don’t Try Your Jive On Me” and two takes of the Waller anthem “Ain’t Misbehavin’” were recorded with the organ before Waller moved to the piano. “Jive” is a forgettable piece of pop tripe and Waller provides a serviceable performance with a full chorus of organ at the start of the recording and a listless vocal. There aren’t many registration changes, but Waller’s organ style retains much of his piano style including a smoothed-out 4/4 swing pattern in the left hand and wry, extended trills in the right. Near the end of the side, Waller tries to rally the band with a few vocal exhortations, but it’s clear that the band was as bored by this song as Waller. “Ain’t Misbehavin’” fares better. At first listen, the first take seems much too slow, but Waller’s sly counterpoint and sinuous melodic variations during his opening solo chorus makes the tempo seem absolutely right. The second take was chosen as the master, and the tempo is noticeably faster and fine on its own terms. In the last eight of his solo chorus here, he bounces the melodic variations between the organ’s three manuals with different registrations used for each. Waller must have sang this song a few thousand times during his career, but he still found fresh ways to sing the lines and to back them up on the keyboard.

A week later, Waller returned to Abbey Road and recorded six organ solos. Four of the songs were authentic spirituals and the other two were pop songs inspired by spirituals. Waller, who was profoundly religious all his life, treats these songs with great respect, and creates a stunning suite in the process. “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” opens with a long and flashy introduction, and the arrangement features rich registration, re-imagined harmony, a steady yet swinging beat, and an effective quiet coda. “All God’s Children” alternates a bouncing rhythm style with solemn, slow episodes. Waller’s choice of organ registration may seem over-the-top to modern ears, but one must remember that these recordings were made before lesser organists overused these sounds in accompanying soap operas and game shows. “Go Down, Moses” is the standout side of the suite, with a dramatic performance of the melody and glorious use of mixed stops. Waller creates great dynamic contrasts through the volume pedal, and for once, the effect fits the material. The coda is especially stunning with booming bass from the pedals and church-like registration leading to a sudden pianissimo ending. Waller fits “Deep River” with a steady quarter note bass pattern, interrupting the bass only when the melody demands a dramatic emphasis. Before he shifts to a quicker tempo for the coda, there is a brief episode with contrary-motion solo lines in the manual and pedals. On “Water Boy”, Waller sets off portions of the melody in unaccompanied rubato lines, then breaks the tension with a light-hearted, strutting variation for the next chorus. “Lonesome Road” concludes the set, and Waller takes greater liberty with the melody and plays his only full-blown improvisation of the suite. While some may question the jazz content of the suite as a whole, “Lonesome Road” features the greatest concentration of swing in the entire set.

Near the end of the session, vocalist Adelaide Hall joined Waller for two duets.  Despite her brief tenure with Duke Ellington, Hall (below) was not really a jazz singer, and her sudden leaps in pitch on “That Old Feeling” seem like a nervous habit instead of a manner of jazz expression. Waller counters her exaggerated emotions with witty vocal asides. Hall was in on the joke to some degree: on the second chorus of “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”, she finishes the title line with my little fat baby; Waller responds “Oh baby, don’t talk like that!” Waller seemed to like the format of this duet and recorded the song again the next year with the Rhythm and guest vocalist Una Mae Carlisle. Before Waller returned to the States, Hall and Waller reprised their duets for a shortwave broadcast from St. George’s Hall. While Waller was still playing a Compton organ at St. George’s, he uses different registrations here than he had on the organ at Abbey Road, and partially because of these registrations, the overall sound of the broadcast tends to favor the organ. Waller had recorded Slim Gaillard’s “Flat Foot Floogie” on piano at the Continental Rhythm session and here he quickly adapts it into an organ/vocal duet that swings mightier than any of his other London organ sides. Hall sings with abandon, despite the fact that she had probably never sung the song before. The performance doesn’t really end; it just melds into a brief version of “Ain’t Misbehavin’” as the broadcast ends.

Despite her brief tenure with Duke Ellington, Hall (below) was not really a jazz singer, and her sudden leaps in pitch on “That Old Feeling” seem like a nervous habit instead of a manner of jazz expression. Waller counters her exaggerated emotions with witty vocal asides. Hall was in on the joke to some degree: on the second chorus of “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”, she finishes the title line with my little fat baby; Waller responds “Oh baby, don’t talk like that!” Waller seemed to like the format of this duet and recorded the song again the next year with the Rhythm and guest vocalist Una Mae Carlisle. Before Waller returned to the States, Hall and Waller reprised their duets for a shortwave broadcast from St. George’s Hall. While Waller was still playing a Compton organ at St. George’s, he uses different registrations here than he had on the organ at Abbey Road, and partially because of these registrations, the overall sound of the broadcast tends to favor the organ. Waller had recorded Slim Gaillard’s “Flat Foot Floogie” on piano at the Continental Rhythm session and here he quickly adapts it into an organ/vocal duet that swings mightier than any of his other London organ sides. Hall sings with abandon, despite the fact that she had probably never sung the song before. The performance doesn’t really end; it just melds into a brief version of “Ain’t Misbehavin’” as the broadcast ends.

In 1939, Waller recorded his two final recordings on pipe organ during a return trip to London. On “Smoke Dreams Of You”, Waller sings the song straight, and in his instrumental chorus, he creates an organ effect that seems to emulate the smoke rings in the lyric. “You Can’t Have Your Cake & Eat It” is as undistinguished of a song as its title implies. Waller gives it the satirical treatment it deserves, complete with a break into a baby voice. But his brief improvised solo makes the whole side worthwhile: the powerful riffs and strong pedal bass makes the Compton sound like a big band, and the strong rhythmic impetus continues through the rest of the record.

Waller recorded several more organ sides before his death in 1943, but all of those sides were made on a Hammond organ he purchased around 1938. There were obvious advantages to the electronic instrument: Waller could play it at home (there are many tales of late night organ performances at his residence) plus he could bring it to recording sessions and live concerts. While the sound of the Hammond was not as mighty as the Estey or Compton organs, it seemed to suit him well and among the recordings he made on the Hammond, “Jitterbug Waltz” (with the Rhythm and a big band), “Someone To Watch Over Me” (a duet with Lee Wiley) and “Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child” (solo) are standouts. And in an eerie coincidence, Waller’s organ discography ends nearly where it began: with a solo performance of the “St. Louis Blues”. While the styles of the two recordings are quite different, the arrangements are similar. While he couldn’t have planned it that way (Waller was only 39 when he died), there is an odd symmetry to this portion of the Fats Waller discography.

Much of the information on the Estey organ was taken from Paul S. Machlin’s book “Stride: The Music of Fats Waller” (Twayne, 1985). Online resources include The Estey Organs Opus ist, Stokowski.org & VJM Jazz & Blues Mart. Thanks to Dan Morgenstern for general guidance.

The audio recordings embedded in this article are presented for educational and illustrative purposes. Jazz History Online neither owns nor controls the rights to these recordings. All rights belong to the original copyright holders.

FOR ALL OF YOU PIPE ORGAN GEEKS (you know who you are), here are the specifications for the Victor Estey pipe organ (copied from Paul Machlin’s book “Stride: The Music of Fats Waller”):

Opus 2370

Three manual pipe organ with pedals

Compass of manuals CC to C4, 61 notes

Compass of pedals CCC to G 32 notes

Great Organ:

open diapason 8′

First open diapason 8′

Second open diapason 8′

Major flute 8′

Flute 8′

Gamba 8′

Gemshorn 8′

Viol d’Orchestre 8′

Viol Celeste 8′

Flute 8′

Flute harmonic 8′

Oboe 8′

Cornopean (in place of trumpet) 8′

Clarinet 8′

Saxophone 8′

Vox Humana 8′

Swell Organ:

All stops duplicated from Great, with addition of Tremolo

Solo Organ:

Stentorphone 8′

Tibia Plena 8′

Gross Gamba 8′

Gamba Celeste 8′

First Violin III ranks

Flute 4′

Piccolo Harmonic 2′

Orchestral Oboe 8′

Tuba Profunda 16′

Tuba 8′

Clarion 4′

Pedal Organ:

Open diapason 16′

Bourdon 16′

Bass Viol 8′

Trombone 16′

Tuba 8′