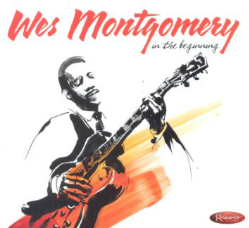

Wes Montgomery’s time in the national spotlight lasted just over a decade,  from his late-1957 debut session on World Pacific to his premature death in June 1968. His popularity increased with each new label affiliation, as he moved from World Pacific to Riverside, and then to Verve and A&M. Montgomery’s style was already in its mature phase during this time, as he had been playing guitar since 1942, and had played professionally since 1944. Resonance Records, which has already presented several unreleased tracks from 1957-1958 on its acclaimed “Echoes of Indiana Avenue” album, has now filled more discographical gaps with their new Montgomery release, “In the Beginning, 1949-1958”. Only four of the 26 tracks from this 2-CD set have been released before, and those four were only issued on small labels or anthologies.

from his late-1957 debut session on World Pacific to his premature death in June 1968. His popularity increased with each new label affiliation, as he moved from World Pacific to Riverside, and then to Verve and A&M. Montgomery’s style was already in its mature phase during this time, as he had been playing guitar since 1942, and had played professionally since 1944. Resonance Records, which has already presented several unreleased tracks from 1957-1958 on its acclaimed “Echoes of Indiana Avenue” album, has now filled more discographical gaps with their new Montgomery release, “In the Beginning, 1949-1958”. Only four of the 26 tracks from this 2-CD set have been released before, and those four were only issued on small labels or anthologies.

Most of the first disc consists of live recordings made between August and November 1956 at the Turf Club in Montgomery’s home town of Indianapolis. The Turf Club was a whites-only supper club, and according to Wes’ brothers Buddy and Monk, the establishment was barely surviving until they started playing there. By the recorded evidence, the band (which included Alonzo “Pookie” Johnson on tenor sax, Buddy on piano, Wes on guitar, Monk on electric bass and Sonny Johnson on drums) was professional and entertaining. But it is only occasionally that Wes stands out as a star in the making. Many of his solos are single-line showcases that feature his already impressive technique and boundless melodic imagination. He plays a sequence of block chords near the end of a breakneck “My Heart Stood Still”, and we hear his fine sensitive ballad playing on a lovely version of “What is There to Say?” but his building-block style with solos that moved from single lines to octaves and finally to block chords had not been codified yet. Wes used this simple method of solo construction for the rest of his life, and once it was developed, all of his stylistic elements seemed to fall into place. We can hear elements of the style throughout the 1956 recordings—there is a single-line to octaves pattern on a plodding rendition of “How High the Moon” and alternating single-lines and block chords on the fast Latin “Caravan”—but his fully mature style doesn’t appear until two years later. Of course, Wes usually took several choruses to create his mature solos, and in this band, his solo time is limited as Pookie and Buddy take solos on many of the tunes. At this stage, the three men are quite evenly matched. None of them are particularly polished soloists, but the music swings, and it’s what one might expect of a local jazz combo of the time.

Disc 1 ends with a 1956 house jam session on “Ralph’s New Blues” with Wes playing Monk’s electric bass. He walks the blues progression well (especially since he knew very little music theory) and plays a good solo, but otherwise, the track isn’t particularly distinguished. The first three tracks on Disc 2 move us ahead to a live session at the Missile Lounge in Indianapolis. While all of the live Montgomery-Johnson tracks on the first disc run between three and four minutes, the Missile Lounge tracks run about 12 minutes each, and allow everyone to stretch out. Melvin Rhyne’s solo on “Soft Winds” is played on a piano that is as painfully out-of-tune as the instrument Buddy played at the Turf Club. Wes sounds much more assured in his solo than on the earlier dates, and his octave work is quite impressive. Unfortunately, bassist Flip Stewart and drummer Paul Parker can’t hold the relaxed tempo, and it’s very apparent when the tempo surges ahead. On “Robbins’ Nest” and “A Night in Tunisia”, Richie Crabtree and Monk Montgomery replace Rhyne and Stewart. On “Robbins’”, Monk holds the tempo steady, and after a long solo by Crabtree, we finally hear Wes play a solo in his fully-developed mature style.

The Missile Lounge set was the logical place for the album to end (and that was the original plan according to producer Zev Feldman’s notes). However, more unissued Montgomery material surfaced and rather than adjusting the track sequence, the extra tracks were plopped at the end of disc 2. So, after hearing the mature Montgomery of 1958, we go back three years—before the live dates that opened the set—for a Quincy Jones-produced session by the Montgomery-Johnson Quintet for Epic Records. From there, we move forward again to 1957 (between the two live sets) for a single jam session track with Wes and Pookie in Chicago, and then backwards again to 1949 for three sides from a four-side session by Gene Morris and his Hamptones. I don’t understand why this album wasn’t sequenced to illustrate Wes Montgomery’s development as a master jazz musician. Sure, anyone with an iPod or a CD changer can re-sequence this album themselves, but shouldn’t that be done for us by the producers?

Now for the record, the Epic session is a real find. The band was still a little rough around the edges (part of which could be attributed to nerves) but there was no other apparent reason for this music to remain unissued—and basically forgotten—for all these years. The Chicago jam on “All the Things You Are” has another building-block solo, but Wes was clearly unprepared to play on Jerome Kern’s highly chromatic chord changes, and the wrong notes fly out from nearly every phrase. I am truly surprised that the Montgomery family allowed this track to be released. The 1949 Gene Morris tracks straddle the line between R&B and jazz. They are well-played, but based on the three cuts included here, I’m not inclined to seek out an import CD to obtain the remaining track.

There is no question that George Klabin and Zev Feldman have done the jazz community a great service by issuing these rare Wes Montgomery tracks. They are not nearly as revelatory as annotator Bill Milkowski would have you believe, but with the exception of the “All the Things” jam, all of the music is well played and worthy of issue. As usual with Resonance, the booklet is loaded with well-researched historical information (in this case, with notes by Ashley Kahn and Milkowski, excerpts from memoirs by Buddy and Monk Montgomery, and interviews with Quincy Jones and Duncan Scheidt). The remastered sound is excellent, and for those who prefer to listen on vinyl, the entire collection is available as a 3-LP set.