Vibraphonist Joe Locke’s (left) fame has grown considerably over the last five years through a series of recordings on the Motéma label. However, he has been known as a “musician’s musician” since he first appeared on the New York scene in the early 1980s. His range is truly remarkable, and he has worked with leaders as diverse as Dizzy Gillespie, Grover Washington, Jr., Dianne Reeves, Jerry Gonzalez and Cecil Taylor. Two new albums, scheduled to be released within the same week, offer further evidence of his flexibility. Each album is dedicated to the work of a single composer—one featuring the works of Gary McFarland, and the other, of Joe Locke himself.

Vibraphonist Joe Locke’s (left) fame has grown considerably over the last five years through a series of recordings on the Motéma label. However, he has been known as a “musician’s musician” since he first appeared on the New York scene in the early 1980s. His range is truly remarkable, and he has worked with leaders as diverse as Dizzy Gillespie, Grover Washington, Jr., Dianne Reeves, Jerry Gonzalez and Cecil Taylor. Two new albums, scheduled to be released within the same week, offer further evidence of his flexibility. Each album is dedicated to the work of a single composer—one featuring the works of Gary McFarland, and the other, of Joe Locke himself.

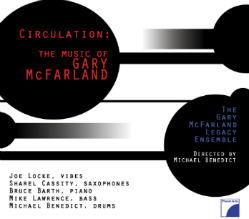

The McFarland tribute, “Circulation” (Planet Arts 301523) is lead by drummer Michael Benedict. In addition to producing and performing on this album, Benedict’s connection to McFarland is also familial, as he married McFarland’s widow in 1981. The album includes music from throughout McFarland’s protracted career, including several pieces composed while he was a student at Berklee. The opener, “Dragonhead” is one of those early pieces, but the band (Locke, Benedict, plus saxophonist Sharel Cassity, pianist Bruce Barth and bassist Mike Lawrence) makes it sound completely contemporary with brilliant quartal harmony and an energetic performance. Locke takes the spotlight for “Why Are You Blue”, a piece originally composed for a Johnny Hodges album, and just within these first two tracks, we hear significantly different solos from him: on “Dragonhead”, his attention is on the quickly moving harmony, but the slow Hodges blues brings out more of his melodic side. It’s fascinating to hear Locke’s work in context. He has a unique ability to create solos which stand perfectly well on their own, but also provide commentary on what has come before. For example, on the ballad “One I Could Have Loved”, Locke has the unenviable task of following Cassity’s emotionally overwhelming alto solo, yet his solo answers Cassity’s passion without trying to top it. His solo on “Chuggin’” amplifies the grit and soulfulness displayed in Barth’s remarkable block-chord solo (If further evidence is required of the simpatico relationship of Locke and Barth, there is the superb series of four-bar exchanges on “Notions” and their brief dual improvisation near the end of the title track). Locke gets the last track to himself, with a lovely solo rendition of “Last Rites for the Promised Land”, written for McFarland’s 1968 LP, “America the Beautiful.” Barth wrote all of the arrangements for the album, and they embrace a wide range of sub-genres (including modal, quartal, bop, cool and blues). The ensemble plays all of these styles with great panache, which says a lot for them as well as McFarland.

throughout McFarland’s protracted career, including several pieces composed while he was a student at Berklee. The opener, “Dragonhead” is one of those early pieces, but the band (Locke, Benedict, plus saxophonist Sharel Cassity, pianist Bruce Barth and bassist Mike Lawrence) makes it sound completely contemporary with brilliant quartal harmony and an energetic performance. Locke takes the spotlight for “Why Are You Blue”, a piece originally composed for a Johnny Hodges album, and just within these first two tracks, we hear significantly different solos from him: on “Dragonhead”, his attention is on the quickly moving harmony, but the slow Hodges blues brings out more of his melodic side. It’s fascinating to hear Locke’s work in context. He has a unique ability to create solos which stand perfectly well on their own, but also provide commentary on what has come before. For example, on the ballad “One I Could Have Loved”, Locke has the unenviable task of following Cassity’s emotionally overwhelming alto solo, yet his solo answers Cassity’s passion without trying to top it. His solo on “Chuggin’” amplifies the grit and soulfulness displayed in Barth’s remarkable block-chord solo (If further evidence is required of the simpatico relationship of Locke and Barth, there is the superb series of four-bar exchanges on “Notions” and their brief dual improvisation near the end of the title track). Locke gets the last track to himself, with a lovely solo rendition of “Last Rites for the Promised Land”, written for McFarland’s 1968 LP, “America the Beautiful.” Barth wrote all of the arrangements for the album, and they embrace a wide range of sub-genres (including modal, quartal, bop, cool and blues). The ensemble plays all of these styles with great panache, which says a lot for them as well as McFarland.

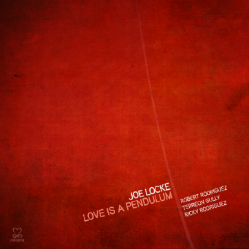

“Love is a Pendulum” (Motéma 173) is an intensely personal statement by Locke. Its centerpiece is his five-movement suite inspired by a poem by Barbara Sfraga, which describes different aspects of love. By his own admission, most of this music is tightly composed, but Locke has done an admirable job of creating a work that straddles the worlds of composed and improvised music. So while the listener can easily discern the depictions of ocean  waves in “Love is the Tide”, the improvisations comment and illuminate the composed lines. Indeed, Locke’s dramatic solos provide this music with much of its inner soul. I’ve rarely heard Locke play with as much passion as on this recording. It’s not surprising for a composer to be emotionally tied to his work, but there seems to be more than that in Locke’s performances, as if there is a deeper message to this music than merely a collection of melodies, harmonies and rhythms. Locke created this work for his “core quartet” of Robert Rodriguez (piano), Ricky Rodriguez (bass) and Terreon Gully (drums), but he has included guest artists on each track, including saxophonists Rosario Giuliani and Donny McCaslin, guitarist Paul Bollenback, steel pan drummer Victor Provost and vocalist Theo Bleckmann. Sometimes these guests appear only to add color to the ensemble (Bleckmann’s multi-tracked introduction and coda to “Love is a Planchette” being a specific example), while other tracks were specifically designed as showcases for the guests (as in Provost’s feature on the closer “Embrace”). It’s clear that these musicians all share Locke’s passion for this music, and as Locke’s solos on the McFarland album amplified those of his fellow musicians, Locke’s sidemen enhance his statements. The dovetailed lines of Locke and Guiliani on the rubato ballad “Love is Letting Go” are a particularly inspired example of this, as are the exchanges between Locke and Provost on “Love is Perpetual Motion”. While the compositions on “Love is a Pendulum” are not as varied as those on the McFarland tribute, the broad variety of instrumental colors are a worthy substitute. And for anyone wanting a solid introduction to the work of Joe Locke, both of these albums come highly recommended.

waves in “Love is the Tide”, the improvisations comment and illuminate the composed lines. Indeed, Locke’s dramatic solos provide this music with much of its inner soul. I’ve rarely heard Locke play with as much passion as on this recording. It’s not surprising for a composer to be emotionally tied to his work, but there seems to be more than that in Locke’s performances, as if there is a deeper message to this music than merely a collection of melodies, harmonies and rhythms. Locke created this work for his “core quartet” of Robert Rodriguez (piano), Ricky Rodriguez (bass) and Terreon Gully (drums), but he has included guest artists on each track, including saxophonists Rosario Giuliani and Donny McCaslin, guitarist Paul Bollenback, steel pan drummer Victor Provost and vocalist Theo Bleckmann. Sometimes these guests appear only to add color to the ensemble (Bleckmann’s multi-tracked introduction and coda to “Love is a Planchette” being a specific example), while other tracks were specifically designed as showcases for the guests (as in Provost’s feature on the closer “Embrace”). It’s clear that these musicians all share Locke’s passion for this music, and as Locke’s solos on the McFarland album amplified those of his fellow musicians, Locke’s sidemen enhance his statements. The dovetailed lines of Locke and Guiliani on the rubato ballad “Love is Letting Go” are a particularly inspired example of this, as are the exchanges between Locke and Provost on “Love is Perpetual Motion”. While the compositions on “Love is a Pendulum” are not as varied as those on the McFarland tribute, the broad variety of instrumental colors are a worthy substitute. And for anyone wanting a solid introduction to the work of Joe Locke, both of these albums come highly recommended.