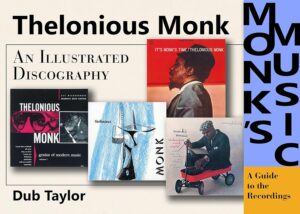

Discographies are rather dry volumes. Originally published from photocopies of typewritten pages, these books—designed for serious musicologists and dedicated fans—are essentially collections of names and catalog numbers. They provide a guide to an artist’s history through their recordings, including full personnel for each session and all known issues of the recordings. In sharp contrast to standard discographies, “Monk’s Music” (Genius), Dub Taylor’s expansive discography of Thelonious Monk, is a dazzling display of bright colors and intriguing design. Taylor’s work fulfills most of the primary functions of a discography, while adding full-color photos of album covers and record labels.

The recording history of Thelonious Monk is a tangled one. Monk played at Minton’s Playhouse in 1941 as he, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, and others developed the language of bebop. Jerry Newman, a student at Columbia University owned a primitive disc recorder and—with the artists’ permission—he recorded the evolving music. Unfortunately, Newman didn’t always identify all of the musicians on the recordings (a trait shared by other amateur recordists of the time) and to this day, jazz fans and historians still argue about who appears on what tracks. Taylor does an admirable job of sorting out the conflicting personnel, but he seems a little too willing to omit items where the pianist is listed as “possibly” or “probably” Monk. Once we reach 1947, the year of Monk’s first recordings as a leader (for the fabled Blue Note label) the documentation has more certainties and less guesswork.

The recording history of Thelonious Monk is a tangled one. Monk played at Minton’s Playhouse in 1941 as he, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, and others developed the language of bebop. Jerry Newman, a student at Columbia University owned a primitive disc recorder and—with the artists’ permission—he recorded the evolving music. Unfortunately, Newman didn’t always identify all of the musicians on the recordings (a trait shared by other amateur recordists of the time) and to this day, jazz fans and historians still argue about who appears on what tracks. Taylor does an admirable job of sorting out the conflicting personnel, but he seems a little too willing to omit items where the pianist is listed as “possibly” or “probably” Monk. Once we reach 1947, the year of Monk’s first recordings as a leader (for the fabled Blue Note label) the documentation has more certainties and less guesswork.

Along with Monk’s later commercial recordings for Prestige, Riverside, and Columbia, we see an increasing number of live performances, many of which were released on bootleg labels. Taylor’s extensive research reveals rare cover images of these unauthorized albums (Surprisingly, most of the album covers shown in the book bear the correct spelling of Monk’s first name; however, page 24 lists two of the most common misspellings: “Theolonious” and “Thelonius”. The irony is that at least one of these albums is an authorized recording!) One of the most welcome features of Taylor’s book is the inclusion of video recordings. These documentary and performance videos are essential parts of Monk’s story, as they include interviews with the pianist (with his typically cryptic responses to the journalist’s unimaginative questions) and concert footage (displaying Monk’s unique approach to the keyboard and his highly personal terpsichorean skills). I was especially pleased to find a listing for “The Jazz Loft“, a documentary about W. Eugene Smith, who invited Monk and a specially formed big band to his loft, so they could rehearse for their 1959 Town Hall concerts. Taylor even lists the length of the segment featuring recordings of the rehearsals!

The book is organized chronologically by recording dates. Albums containing the same material are usually listed together. Here, Taylor’s approach varies from standard discographical practice, where albums with even the slightest differences are given separate entries. For example, the 1983 Mosaic collection of Monk’s complete Blue Note studio recordings did not include the 1958 live set from the Five Spot. That live performance was discovered and issued in 1993, and a speed-corrected version was released the following year as part of Blue Note’s 4-CD boxed set of Monk’s recordings. Yet despite the obvious differences, Taylor lists both albums in the same entry. While Taylor explains these differences within a small text box, he offers little assistance when listing the original Blue Note LP issues of this material. In the early 1950s, Blue Note released 2 10-inch LPs of Monk’s recordings titled “Genius of Modern Music”. Monk’s master and alternate takes were scattered in a highly random fashion across the two volumes, and the confusion only grew worse when the albums were expanded and reissued on 12-inch LPs. Taylor lists all of the tracks which appear on these albums, but without any indication of what tracks (and takes) appear on each LP. He tries to explain this problem away by stating—truthfully—that the CD versions have all of the music in chronological order. But Taylor must be unaware that the current trends in music lean toward vinyl issues that duplicate the track order of the original albums! This leads us to another problem: the omission of matrix numbers. These numbers were created by the record companies to identify individual performances (including multiple takes of the same songs). While matrix numbers are no longer etched into the lead-out grooves of discs, they are still valuable tools for researchers striving to identify specific versions of a given song. Virtually every major discography is structured on these numbers, and because of their absence, Taylor’s book risks being dismissed by the very scholars it should attract. In future editions, I would recommend this addition of matrix numbers, along with a color-coded guide to the contents of each album. And while we’re at it, why not include cover reproductions of the popular 2-LP reissues issued in the 1970s? Those records sold fairly well, and are commonly found in used record stores (both brick-and-mortar and online).

There needs to be one more addition to Taylor’s book (and this was not his fault, as it appeared after his book went to press): A newly discovered—and revelatory—session was just issued on Mosaic’s new collection of Don Byas recordings from 1944-1946. It documents a 1944 jam session at the apartment of Danish jazz promoter Timme Rosenkrantz, with the young Monk leading the session from the keyboard, giving instructions and guiding the performances. It provides rarely heard examples of Monk as a highly efficient bandleader. The only track from this session issued before the Mosaic set was on a Danish Storyville CD called “Timme’s Treasures” (one of the few discs Taylor missed). A revised edition including this session will not only add another valuable recording to Monk’s recorded legacy but also expand our knowledge of Thelonious Monk, the artist.