LYNNE ARRIALE: “BEING HUMAN” (Challenge 73572)

In Billy Wilder‘s classic film, “The Apartment“, Dr. Dreyfuss (played by Jack Kruschen) gives sage advice to his neighbor, C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon): Be a mensch. When Baxter shows confusion, the exasperated doctor clarifies, saying a mensch; a human being. There is a lot of responsibility in being a mensch, including endless compassion for other people. Social media and divisive politics have caused us to be less mensch-like, but pianist Lynne Arriale‘s new album “Being Human” features music that should encourage us to improve our  behavior and outlook. Arriale’s album-length suite features ten movements, with dedications ranging from prominent individuals like Greta Thunberg and Amanda Gorman to large groups including the population of Ukraine, people of faith, and all of humankind. “Passion” opens with a rush of sounds before settling into a lyric, yet intense groove. Arriale’s searing improvisation explores Thunberg’s toughness without ignoring the sensitivity that comes with her youth. “Courage” feels like an anthem for the Ukranians. Drummer Łukasz Żyta maintains the pulse with a strong backbeat while bassist Alon Near‘s countermelodies support Arriale’s stirring solo. “Love” has a chorale-styled melody with pointed dissonances within the harmonization. As Arriale and Near outline the melody, Zyta adds cymbal rolls to increase the drama. “Faith” is an enlightening piece of gospel music featuring a lilting piano solo over a righteous groove. The autistic mathematician Jacob Barnett is the subject of “Curiosity”, a free improvisation that builds to an impressive climax fueled by the interweaving lines of the three musicians. “Soul” for Gorman is based on a bluesy vamp, and Arriale creates remarkable variations with each repetition of the form. Malala Yousafzai‘s “Persistence” supporting education for all Pakistani children inspired Arriale’s modal composition and a well-developed three-way musical conversation. “Heart” takes us back to Ukraine for a portrait of the dedicated chief nurse at Kharkiv Oblast Hospital, Khrystyna Lopatenko. This is another case of Arriale bringing awareness to unsung heroes. The UN’s online story about Lopatenko is truly inspiring and worth your attention, as is the subject of “Gratitude”, the late author and motivational speaker, Mattie Stepanek. “Joy” is a thrilling tribute to Brené Brown, whose TED talk “The Power of Vulnerability” has inspired millions to find joy within themselves. A reprise of “Love” with synthesized voices concludes the album. At 40 minutes with 11 tracks, this album is vinyl-friendly and radio-friendly, but less amiable to the musicians. Arriale is in magnificent form throughout, but she should have provided generous solo space for her sidemen (as I’m sure they received in live performances). The truly unnecessary brevity of this album is a substantial flaw for this otherwise outstanding recording.

behavior and outlook. Arriale’s album-length suite features ten movements, with dedications ranging from prominent individuals like Greta Thunberg and Amanda Gorman to large groups including the population of Ukraine, people of faith, and all of humankind. “Passion” opens with a rush of sounds before settling into a lyric, yet intense groove. Arriale’s searing improvisation explores Thunberg’s toughness without ignoring the sensitivity that comes with her youth. “Courage” feels like an anthem for the Ukranians. Drummer Łukasz Żyta maintains the pulse with a strong backbeat while bassist Alon Near‘s countermelodies support Arriale’s stirring solo. “Love” has a chorale-styled melody with pointed dissonances within the harmonization. As Arriale and Near outline the melody, Zyta adds cymbal rolls to increase the drama. “Faith” is an enlightening piece of gospel music featuring a lilting piano solo over a righteous groove. The autistic mathematician Jacob Barnett is the subject of “Curiosity”, a free improvisation that builds to an impressive climax fueled by the interweaving lines of the three musicians. “Soul” for Gorman is based on a bluesy vamp, and Arriale creates remarkable variations with each repetition of the form. Malala Yousafzai‘s “Persistence” supporting education for all Pakistani children inspired Arriale’s modal composition and a well-developed three-way musical conversation. “Heart” takes us back to Ukraine for a portrait of the dedicated chief nurse at Kharkiv Oblast Hospital, Khrystyna Lopatenko. This is another case of Arriale bringing awareness to unsung heroes. The UN’s online story about Lopatenko is truly inspiring and worth your attention, as is the subject of “Gratitude”, the late author and motivational speaker, Mattie Stepanek. “Joy” is a thrilling tribute to Brené Brown, whose TED talk “The Power of Vulnerability” has inspired millions to find joy within themselves. A reprise of “Love” with synthesized voices concludes the album. At 40 minutes with 11 tracks, this album is vinyl-friendly and radio-friendly, but less amiable to the musicians. Arriale is in magnificent form throughout, but she should have provided generous solo space for her sidemen (as I’m sure they received in live performances). The truly unnecessary brevity of this album is a substantial flaw for this otherwise outstanding recording.

FRANCO AMBROSETTI WITH STRINGS: “SWEET CARESS” (Enja 9852)

In 1955, when he was only 25 years old, newly married, and a rising star on the jazz scene, Clifford Brown recorded one of his most profound albums, “Clifford Brown with Strings“. It was a recording that inspired musicians all over the world, including a 15-year-old trumpeter from Lugano, Switzerland named Franco Ambrosetti. By the 1960s, Ambrosetti was one of the major jazz soloists in Europe. As he approached his 82nd birthday, he recorded a new album with strings to celebrate Clifford’s legacy and the remarkable  contemporary musicians who helped him realize the tribute. The album, “Sweet Caress” is a flawless recording captured in stereo and immersive surround sound by engineers Jim Anderson, Ulrike Schwarz, and Steven Sacco, featuring the talents of arranger/conductor Alan Broadbent, concertmistress Sara Caswell, guitarist John Scofield, bassist Scott Colley, drummer Peter Erskine, and of course, the leader and flugelhornist. Ambrosetti’s heartfelt solos on “Soul Eyes” and “Portrait of Jennie”—the latter song a holdover from Brownie’s album—sets the stage for a recital of unmatched beauty and tenderness. The title tune is a true act of kindness, as Ambrosetti lays out to feature his accomplished violinist. Caswell’s glorious tone is spectacularly recorded (nowhere better than in the 7.1 surround master I heard in New York with Anderson and Schwarz as my audio guides) and her performance of the melody will bring tears to the most jaded eyes. The sweeping arcs of her variations only add to the delicate melancholy of this piece. Scofield acts as the secondary soloist through most of the album, rendering some of his most tasteful playing in recent memory. Broadbent’s scores draw our attention at all the right places and supports with subtlety everywhere else. His setting of Ambrosetti’s gentle “Habanera” is very resourceful with lines that interact with the soloists both for melodic statements and improvisations. Colley adds his solo voice to a rare Charlie Haden composition, “Nightfall”, and while Erskine does not get any solos on this ballad-heavy recital, his work rewards close listening. As Jamey Aebersold once told me, “The patterns Peter plays are so simple, but they feel so right”. Ambrosetti’s profound, mature statements on this album proves that the ballad album is still a viable form with lots of room for creativity. Get a copy of this album—in surround if your home stereo can handle the additional audio information—and settle in for a wondrous hour of glorious music. [Sara Caswell was prominently featured in another outstanding release of 2024, Ryan Truesdell‘s “Synthesis” (Artist Share 228) where Caswell led a string quartet in a collection of contemporary classical and jazz-influenced works, all commissioned by Truesdell during the pandemic.]

contemporary musicians who helped him realize the tribute. The album, “Sweet Caress” is a flawless recording captured in stereo and immersive surround sound by engineers Jim Anderson, Ulrike Schwarz, and Steven Sacco, featuring the talents of arranger/conductor Alan Broadbent, concertmistress Sara Caswell, guitarist John Scofield, bassist Scott Colley, drummer Peter Erskine, and of course, the leader and flugelhornist. Ambrosetti’s heartfelt solos on “Soul Eyes” and “Portrait of Jennie”—the latter song a holdover from Brownie’s album—sets the stage for a recital of unmatched beauty and tenderness. The title tune is a true act of kindness, as Ambrosetti lays out to feature his accomplished violinist. Caswell’s glorious tone is spectacularly recorded (nowhere better than in the 7.1 surround master I heard in New York with Anderson and Schwarz as my audio guides) and her performance of the melody will bring tears to the most jaded eyes. The sweeping arcs of her variations only add to the delicate melancholy of this piece. Scofield acts as the secondary soloist through most of the album, rendering some of his most tasteful playing in recent memory. Broadbent’s scores draw our attention at all the right places and supports with subtlety everywhere else. His setting of Ambrosetti’s gentle “Habanera” is very resourceful with lines that interact with the soloists both for melodic statements and improvisations. Colley adds his solo voice to a rare Charlie Haden composition, “Nightfall”, and while Erskine does not get any solos on this ballad-heavy recital, his work rewards close listening. As Jamey Aebersold once told me, “The patterns Peter plays are so simple, but they feel so right”. Ambrosetti’s profound, mature statements on this album proves that the ballad album is still a viable form with lots of room for creativity. Get a copy of this album—in surround if your home stereo can handle the additional audio information—and settle in for a wondrous hour of glorious music. [Sara Caswell was prominently featured in another outstanding release of 2024, Ryan Truesdell‘s “Synthesis” (Artist Share 228) where Caswell led a string quartet in a collection of contemporary classical and jazz-influenced works, all commissioned by Truesdell during the pandemic.]

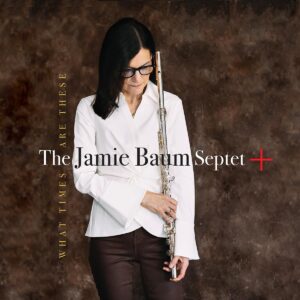

JAMIE BAUM SEPTET PLUS: “WHAT TIMES ARE THESE?” (Sunnyside 1722)

When COVID-19 closed down the performing arts world, flutist Jamie Baum retreated to her Manhattan apartment and started to compose, not knowing when or if the music would ever be performed. She found inspiration through a series of poems presented on a Bill Moyers website, and selected eight works—all by contemporary female poets—to set for her septet, augmented with guest vocalists and speakers. The compositions were recorded in April 2023 and are now available on the album “What Times Are These?” The breadth of Baum’s compositional vision is immediately apparent in the opening salvo, “In the Light of Day” where an insistent repeated note is played over a richly-scored passage for the septet’s four horns. Baum reads the first poem, Marge Piercy‘s “To Be of Use” over Sam Sadigursky‘s expressive low-register clarinet and Luis Perdomo‘s delicate piano. The text tells of dedicating hard work to your community, and after the reading, Baum gradually adds the other instruments, giving each musician a unique role in creating the musical fabric. Baum’s setting of Tracy K. Smith‘s prophetic “The Old Story” incorporates a rhythmic framework from Aaron Parks‘ “Professor Strangeweather” played by bassist Ricky Rodriguez. The first stanza is read by Jonathan Finlayson, and then repeated with an angular melody, sung with astounding precision by Aubrey Johnson. There are fine solos by Finlayson (trumpet), Brad Shepik (guitar), and Perdomo (Rhodes piano) with interjections and further texts from the two voices. A digitally-looped Theo Bleckmann opens “In Those Years” with an atmospheric chorale before he sings Adrienne Rich‘s verse in a high tenor register. Later, Bleckmann sings a dazzling series of detached notes on the poem’s final word “I” to emphasize the poem’s theme of narcissism. Sadigursky’s alto sax and Perdomo’s acoustic piano provide alternate narratives that contrast with Bleckmann’s intense vocal. A brief drum passage from Jeff Hirschfield bridges the arrangement back to Bleckmann’s solo voice and virtual choir. The title track features Sara Serpa‘s pure soprano singing a challenging melody on Rich’s existential text. The septet plays a well-written background behind Serpa’s vocal, with Shepik as the contrasting instrumental voice. “Sorrow Song” combines a contemporary hip-hop poem written and performed by Kokayi, segued directly into his reading of Lucile Clifton‘s poem from a generation earlier. Baum plays a brilliant solo enhanced by electronic doubling an octave below her flute. Shepik follows with a powerful solo, backed by Johnson’s wordless voice and the horns. Serpa returns to sing the next two poems, Naomi Shihab Nye‘s “My Grandmother in the Stars” (which Baum transforms into a dramatic tribute to her mother) and Piercy’s stunning “I Am Wrestling with Despair” (with a 2017 text that details the beginnings of our current social dystopia). After the eerie images of Piercy’s poem, Baum wisely ends the set of vocal collaborations with a wordless performance by Johnson on an original called “Dreams”. In his only solo performance on the album, French hornist Chris Komer opens the track with a fine unaccompanied passage. The final movement “In the Day of Light” presents further examples of Baum’s fine orchestration—especially the combination of Sadigursky’s delicious bass clarinet and Komer’s horn over the percussion of guest artist, Keita Ogawa. If you have not heard Jamie Baum’s music before, be sure to listen to this marvelous album—and please get it on CD, as the booklet features the complete texts of the poems.

and speakers. The compositions were recorded in April 2023 and are now available on the album “What Times Are These?” The breadth of Baum’s compositional vision is immediately apparent in the opening salvo, “In the Light of Day” where an insistent repeated note is played over a richly-scored passage for the septet’s four horns. Baum reads the first poem, Marge Piercy‘s “To Be of Use” over Sam Sadigursky‘s expressive low-register clarinet and Luis Perdomo‘s delicate piano. The text tells of dedicating hard work to your community, and after the reading, Baum gradually adds the other instruments, giving each musician a unique role in creating the musical fabric. Baum’s setting of Tracy K. Smith‘s prophetic “The Old Story” incorporates a rhythmic framework from Aaron Parks‘ “Professor Strangeweather” played by bassist Ricky Rodriguez. The first stanza is read by Jonathan Finlayson, and then repeated with an angular melody, sung with astounding precision by Aubrey Johnson. There are fine solos by Finlayson (trumpet), Brad Shepik (guitar), and Perdomo (Rhodes piano) with interjections and further texts from the two voices. A digitally-looped Theo Bleckmann opens “In Those Years” with an atmospheric chorale before he sings Adrienne Rich‘s verse in a high tenor register. Later, Bleckmann sings a dazzling series of detached notes on the poem’s final word “I” to emphasize the poem’s theme of narcissism. Sadigursky’s alto sax and Perdomo’s acoustic piano provide alternate narratives that contrast with Bleckmann’s intense vocal. A brief drum passage from Jeff Hirschfield bridges the arrangement back to Bleckmann’s solo voice and virtual choir. The title track features Sara Serpa‘s pure soprano singing a challenging melody on Rich’s existential text. The septet plays a well-written background behind Serpa’s vocal, with Shepik as the contrasting instrumental voice. “Sorrow Song” combines a contemporary hip-hop poem written and performed by Kokayi, segued directly into his reading of Lucile Clifton‘s poem from a generation earlier. Baum plays a brilliant solo enhanced by electronic doubling an octave below her flute. Shepik follows with a powerful solo, backed by Johnson’s wordless voice and the horns. Serpa returns to sing the next two poems, Naomi Shihab Nye‘s “My Grandmother in the Stars” (which Baum transforms into a dramatic tribute to her mother) and Piercy’s stunning “I Am Wrestling with Despair” (with a 2017 text that details the beginnings of our current social dystopia). After the eerie images of Piercy’s poem, Baum wisely ends the set of vocal collaborations with a wordless performance by Johnson on an original called “Dreams”. In his only solo performance on the album, French hornist Chris Komer opens the track with a fine unaccompanied passage. The final movement “In the Day of Light” presents further examples of Baum’s fine orchestration—especially the combination of Sadigursky’s delicious bass clarinet and Komer’s horn over the percussion of guest artist, Keita Ogawa. If you have not heard Jamie Baum’s music before, be sure to listen to this marvelous album—and please get it on CD, as the booklet features the complete texts of the poems.

ANAT COHEN QUARTETINHO: “BLOOM” (Anzic 92)

For “Bloom“, the sophomore album by her Quartetinho (pronounced “Quartet-chin-yo”) Anat Cohen spread out a vast canvas that  captures musical genres from all over the globe. This unique combo can move in several different directions at once, and the opening track “The Night Owl” acts as an overture. Starting with an idea from one of Cohen’s clarinet etudes, it shifts genres as frequently as an insomniac changes TV channels. There is a charming episode reminiscent of a Mexican street band that inexplicably segues into a samba in mixed-meter. Pianist Vitor Gonçalves and bassist Tal Mashiach move the piece into straight-ahead jazz. Cohen maintains the mood for a brief solo, but the song’s restless nature soon sets in for the final bars. Mashiach’s “Paco” alternates a catchy clapped background and a propulsive rhythm with a poignant melody stretched over the top. The ever-resourceful percussionist JAmes Shipp uses a handful of instruments to accentuate the stylistic changes and further support the ensemble. The final minutes of this track offer an organically-created climax that truly elevates the spirit. Thelonious Monk‘s playful “Trinkle Tinkle” is a natural for the Quartetinho. The arrangement deconstructs the original melody, and then Cohen plays an inventive solo that develops Monk’s ideas into a completely new piece. Shipp follows with an abstract solo on vibes, while Gonçalves experiments with both time and harmony. The ensemble chorus near the end is full of delightful surprises (which I will not give away). Gonçalves’ “Tango Para Guillermo” was inspired by the music of Astor Piazzolla, but the appearance of Shipp’s vibes also evokes memories of the Modern Jazz Quartet. I don’t know where Shipp and Cohen came up with the infectious rhythm that fuels their joint composition, “Coco Rococo” but the group has lots of fun playing on and around the beat patterns. “Allegro Solemne” from Agustín Barrios Mangoré‘s “La Catedral” is a true change of pace. Drawing inspiration from the counterpoint of J.S. Bach, and the rondos of classical-era concerti, the piece is a great showpiece for the Quartetinho, displaying their ballad and dance styles. The album closes with two compositions by James Shipp, a moody, multi-tempo opus called “Superheroes in the Gig Economy” (with a jaw-dropping free improv) and a slow, thoughtful piece “Friends in Every Manner of Conveyance”. I apologize that I cannot identify some of the genres on this recording (and there well may be several of the genres that have no official name) but I can say that even if you don’t know what to call it, “Bloom” is an exciting musical journey.

captures musical genres from all over the globe. This unique combo can move in several different directions at once, and the opening track “The Night Owl” acts as an overture. Starting with an idea from one of Cohen’s clarinet etudes, it shifts genres as frequently as an insomniac changes TV channels. There is a charming episode reminiscent of a Mexican street band that inexplicably segues into a samba in mixed-meter. Pianist Vitor Gonçalves and bassist Tal Mashiach move the piece into straight-ahead jazz. Cohen maintains the mood for a brief solo, but the song’s restless nature soon sets in for the final bars. Mashiach’s “Paco” alternates a catchy clapped background and a propulsive rhythm with a poignant melody stretched over the top. The ever-resourceful percussionist JAmes Shipp uses a handful of instruments to accentuate the stylistic changes and further support the ensemble. The final minutes of this track offer an organically-created climax that truly elevates the spirit. Thelonious Monk‘s playful “Trinkle Tinkle” is a natural for the Quartetinho. The arrangement deconstructs the original melody, and then Cohen plays an inventive solo that develops Monk’s ideas into a completely new piece. Shipp follows with an abstract solo on vibes, while Gonçalves experiments with both time and harmony. The ensemble chorus near the end is full of delightful surprises (which I will not give away). Gonçalves’ “Tango Para Guillermo” was inspired by the music of Astor Piazzolla, but the appearance of Shipp’s vibes also evokes memories of the Modern Jazz Quartet. I don’t know where Shipp and Cohen came up with the infectious rhythm that fuels their joint composition, “Coco Rococo” but the group has lots of fun playing on and around the beat patterns. “Allegro Solemne” from Agustín Barrios Mangoré‘s “La Catedral” is a true change of pace. Drawing inspiration from the counterpoint of J.S. Bach, and the rondos of classical-era concerti, the piece is a great showpiece for the Quartetinho, displaying their ballad and dance styles. The album closes with two compositions by James Shipp, a moody, multi-tempo opus called “Superheroes in the Gig Economy” (with a jaw-dropping free improv) and a slow, thoughtful piece “Friends in Every Manner of Conveyance”. I apologize that I cannot identify some of the genres on this recording (and there well may be several of the genres that have no official name) but I can say that even if you don’t know what to call it, “Bloom” is an exciting musical journey.

JACQUI DANKWORTH: “WINDMILLS” (Perdido 2401—download only)

A casual glance at the playlist for Jacqui Dankworth‘s new digital album “Windmills” reveals a collection of well-worn standards. However, the originality of Dankworth’s dynamic performances over Charlie Wood‘s imaginative settings make this one of the British singer’s finest recordings to date. The album opens with a sinuous piano vamp, a single flute, and Dankworth’s smoky voice singing the first strain of “London by Night”. A steady tempo and traditional string background are soon established for the remainder of the initial chorus. But then, the BBC Big Band enters in a waltz tempo, Dankworth leads the horns in a wordless ensemble passage, then after the orchestra plays an interlude, the leading lady sings a virtuosic phrase in the waltz tempo, while the original tempo and style returns! “Windmills of Your Mind” has further surprises. After the expected rubato exposition, the pulse is interrupted by a clapping rhythm. With a vocal flourish, the mood becomes Middle Eastern as the uneven percussion hits play under the theme. Dankworth scats a few phrases against the strings before improvising over the claps. Everything comes together in a powerful odd-meter group passage, followed by a rubato chorus where Dankworth displays her astounding range. I was delighted by the funky remake of “Baubles, Bangles and Beads” which somehow inserts a stop-time chorus to feature drummer Ralph Salmins. Jacques Brel‘s “If You Go Away” begs for a dual-tempo treatment, and Wood’s arrangement provides it, with the “If You Stay” section performed as a power ballad. Dankworth retains the emotional heft and loses the prevalent self-pity. Dankworth’s passionate delivery adds drama to “On Raglan Road” a classic Irish song, and she hits all of the right emotional buttons on the poignant ballad “Will You Wait for Me?” The latter is the only track to feature Dankworth with the sole accompaniment of the rhythm section: Wood (piano), Oli Hayhurst (bass) and Salmins (drums). The BBC Big Band appears on four tracks, and when strings are added, the backup is by the Carducci String Quartet or the string nonet Bedazzle, depending on the needs of the arrangement. With such a large production, it seems odd that there is no physical product available. If you download this album, please do the right thing and pay for this music. The musicians deserve it, and the music continues to surprise and delight with repeated listening (I stopped describing the arrangements to maintain some of the unexpected twists and turns of this program). Jacqui Dankworth’s family—check her Wikipedia page if you don’t know her parents and brother—taught her the importance of excellent arrangers and superb backing musicians. “Windmills” transforms the lesson into reality.

A casual glance at the playlist for Jacqui Dankworth‘s new digital album “Windmills” reveals a collection of well-worn standards. However, the originality of Dankworth’s dynamic performances over Charlie Wood‘s imaginative settings make this one of the British singer’s finest recordings to date. The album opens with a sinuous piano vamp, a single flute, and Dankworth’s smoky voice singing the first strain of “London by Night”. A steady tempo and traditional string background are soon established for the remainder of the initial chorus. But then, the BBC Big Band enters in a waltz tempo, Dankworth leads the horns in a wordless ensemble passage, then after the orchestra plays an interlude, the leading lady sings a virtuosic phrase in the waltz tempo, while the original tempo and style returns! “Windmills of Your Mind” has further surprises. After the expected rubato exposition, the pulse is interrupted by a clapping rhythm. With a vocal flourish, the mood becomes Middle Eastern as the uneven percussion hits play under the theme. Dankworth scats a few phrases against the strings before improvising over the claps. Everything comes together in a powerful odd-meter group passage, followed by a rubato chorus where Dankworth displays her astounding range. I was delighted by the funky remake of “Baubles, Bangles and Beads” which somehow inserts a stop-time chorus to feature drummer Ralph Salmins. Jacques Brel‘s “If You Go Away” begs for a dual-tempo treatment, and Wood’s arrangement provides it, with the “If You Stay” section performed as a power ballad. Dankworth retains the emotional heft and loses the prevalent self-pity. Dankworth’s passionate delivery adds drama to “On Raglan Road” a classic Irish song, and she hits all of the right emotional buttons on the poignant ballad “Will You Wait for Me?” The latter is the only track to feature Dankworth with the sole accompaniment of the rhythm section: Wood (piano), Oli Hayhurst (bass) and Salmins (drums). The BBC Big Band appears on four tracks, and when strings are added, the backup is by the Carducci String Quartet or the string nonet Bedazzle, depending on the needs of the arrangement. With such a large production, it seems odd that there is no physical product available. If you download this album, please do the right thing and pay for this music. The musicians deserve it, and the music continues to surprise and delight with repeated listening (I stopped describing the arrangements to maintain some of the unexpected twists and turns of this program). Jacqui Dankworth’s family—check her Wikipedia page if you don’t know her parents and brother—taught her the importance of excellent arrangers and superb backing musicians. “Windmills” transforms the lesson into reality.

HILARY GARDNER: “ON THE TRAIL WITH THE LONESOME PINES” (Anzic 89)

“On the Trail with the Lonesome Pines“, the latest album from vocalist Hilary Gardner might well be tagged as an “Americana” recording.  It combines two uniquely American musical genres—jazz and country music—with a principal influence from another US staple, the cowboy movie. Rather than juxtaposing classic country songs and a jazz ensemble–as accomplished by Sweet Megg on her fine Turtle Bay release, “Bluer than Blue“—Gardner explores the music sung by Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and their pardners in low-budget westerns first shown in movie theatres on Saturday afternoons (and now seen on Turner Classic Movies and Starz Encore Westerns). The songwriters, including Johnny Mercer, Benny Carter, Frank Loesser, Ralph Rainger, Leo Robin, and Al Dubin, were all renowned for their songs for big bands and Broadway shows, but at the time, they were part of the Hollywood studio system. Gardner approaches this music with a warm delivery and relaxed swing, with Justin Poindexter‘s various guitars (including pedal steel) acting as both a foil and accompanist. Bassist Noah Garabedian and drummer Aaron Thurston supply grooves that straddle the two genres without emphasizing the process. Sasha Papernik‘s accordion (added on two tracks) is a welcome touch of atmosphere. One of this album’s greatest attributes is its consistency between tracks: Gardner’s behind-the-beat phrasing, Poindexter’s plaintive harmony vocals, and the uncomplicated backdrops all contribute to a concept album where the whole equals more than the sum of its parts. While the majority of the songs are dreamy slow odes to the beautiful geography of the West—”Along the Navajo Trail”, “Call of the Canyon”, “Lights of Old Santa Fe”, and so on—the occasional up-tempo rides on “Jingle, Jangle, Jingle”, “Cow Cow Boogie” and “I’m an Old Cowhand” provide well-placed breaks from the melancholy mood. Gardner conceived this unique collection during the early days of the pandemic, and along with her other solo albums (which cover songs of New York, classic standards, and the eclectic contemporary group The Bird and the Bee) she displays a broad comprehension of American Pop Music—bolstered by her work with the outstanding vocal trio Duchess. Her great dedication to vintage music, through detailed research and vividly realized performance, makes “On the Trail” another outstanding addition to her impressive discography.

It combines two uniquely American musical genres—jazz and country music—with a principal influence from another US staple, the cowboy movie. Rather than juxtaposing classic country songs and a jazz ensemble–as accomplished by Sweet Megg on her fine Turtle Bay release, “Bluer than Blue“—Gardner explores the music sung by Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and their pardners in low-budget westerns first shown in movie theatres on Saturday afternoons (and now seen on Turner Classic Movies and Starz Encore Westerns). The songwriters, including Johnny Mercer, Benny Carter, Frank Loesser, Ralph Rainger, Leo Robin, and Al Dubin, were all renowned for their songs for big bands and Broadway shows, but at the time, they were part of the Hollywood studio system. Gardner approaches this music with a warm delivery and relaxed swing, with Justin Poindexter‘s various guitars (including pedal steel) acting as both a foil and accompanist. Bassist Noah Garabedian and drummer Aaron Thurston supply grooves that straddle the two genres without emphasizing the process. Sasha Papernik‘s accordion (added on two tracks) is a welcome touch of atmosphere. One of this album’s greatest attributes is its consistency between tracks: Gardner’s behind-the-beat phrasing, Poindexter’s plaintive harmony vocals, and the uncomplicated backdrops all contribute to a concept album where the whole equals more than the sum of its parts. While the majority of the songs are dreamy slow odes to the beautiful geography of the West—”Along the Navajo Trail”, “Call of the Canyon”, “Lights of Old Santa Fe”, and so on—the occasional up-tempo rides on “Jingle, Jangle, Jingle”, “Cow Cow Boogie” and “I’m an Old Cowhand” provide well-placed breaks from the melancholy mood. Gardner conceived this unique collection during the early days of the pandemic, and along with her other solo albums (which cover songs of New York, classic standards, and the eclectic contemporary group The Bird and the Bee) she displays a broad comprehension of American Pop Music—bolstered by her work with the outstanding vocal trio Duchess. Her great dedication to vintage music, through detailed research and vividly realized performance, makes “On the Trail” another outstanding addition to her impressive discography.

CLAIRE MARTIN: “ALMOST IN YOUR ARMS” (Stunt 24062)

In her storied career, British vocalist Claire Martin has embraced standards and new songs with equal passion. Her new album “Almost in Your Arms” is named for a classic song composed by Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, and the disc leads off with Jimmy McHugh‘s “I Feel a  Song Coming On”. However, the balance of this recital focuses on newer music, and it seems that Martin is attempting to equalize the classic and contemporary styles. For example, between the two above songs, Martin and guest Charlie Wood perform a nuanced duet on Tom Waits‘ atmospheric “This One’s from the Heart”. While Martin and Wood could have collaborated on an old chestnut, Waits’ unique song puts an intriguing spin on the playlist. Martin and producer/arranger James McMillan co-wrote a breakup song called “Apparently, I’m Fine” and her performance of the lyric is both compelling and bittersweet. Martin’s rhythm section—Martin Sjöstedt (piano), Niklas Fernqvist (bass) and Daniel Fredriksson (drums)—is outstanding throughout the album, moving across stylistic boundaries with ease and providing strong support for Martin and guest instrumentalists Karl-Martin Almqvist (tenor sax), Nikki Iles (accordion), Mark Jaimes (guitar), Joe Locke (vibes and narration), and McMillan (miscellaneous instruments). In addition to fine songs by Elvis Costello (with music by Burt Bacharach), Rufus Wainwright, and Carole King, Martin has also included two compositions by the talented jazz vocalist, Mark Winkler. Like many other singer-songwriters, Winkler has been the primary interpreter of his music, but it is good to see that Martin has taken notice of Winkler’s abundant talent and has presented his music in vividly creative performances. And for those old-timers who still contend that “they don’t write songs like they used to”, be sure to dig into Martin’s sassy version of Ty Jeffries‘ “Water and Salt” which combines great lyric imagery and an irresistible groove. Albums like “Almost in Your Arms” (and the others covered in these reviews) renew my optimism in the future of vocal jazz. There are plenty of good songs to sing. It may take a little digging and sifting to find them, but they are worth the added effort. And if the right song is not at hand, we can always write a new one to fit the occasion.

Song Coming On”. However, the balance of this recital focuses on newer music, and it seems that Martin is attempting to equalize the classic and contemporary styles. For example, between the two above songs, Martin and guest Charlie Wood perform a nuanced duet on Tom Waits‘ atmospheric “This One’s from the Heart”. While Martin and Wood could have collaborated on an old chestnut, Waits’ unique song puts an intriguing spin on the playlist. Martin and producer/arranger James McMillan co-wrote a breakup song called “Apparently, I’m Fine” and her performance of the lyric is both compelling and bittersweet. Martin’s rhythm section—Martin Sjöstedt (piano), Niklas Fernqvist (bass) and Daniel Fredriksson (drums)—is outstanding throughout the album, moving across stylistic boundaries with ease and providing strong support for Martin and guest instrumentalists Karl-Martin Almqvist (tenor sax), Nikki Iles (accordion), Mark Jaimes (guitar), Joe Locke (vibes and narration), and McMillan (miscellaneous instruments). In addition to fine songs by Elvis Costello (with music by Burt Bacharach), Rufus Wainwright, and Carole King, Martin has also included two compositions by the talented jazz vocalist, Mark Winkler. Like many other singer-songwriters, Winkler has been the primary interpreter of his music, but it is good to see that Martin has taken notice of Winkler’s abundant talent and has presented his music in vividly creative performances. And for those old-timers who still contend that “they don’t write songs like they used to”, be sure to dig into Martin’s sassy version of Ty Jeffries‘ “Water and Salt” which combines great lyric imagery and an irresistible groove. Albums like “Almost in Your Arms” (and the others covered in these reviews) renew my optimism in the future of vocal jazz. There are plenty of good songs to sing. It may take a little digging and sifting to find them, but they are worth the added effort. And if the right song is not at hand, we can always write a new one to fit the occasion.

RON MILES: “OLD MAIN CHAPEL” (Blue Note 94818)

I know the Old Main Chapel well. It is an intimate performance venue on the campus of the University of Colorado in Boulder. As the name implies, the building was originally a church. Much of the theater’s interior was adapted from the original sanctuary, and the room is well-known for its warm acoustics. I reviewed several concerts at Old Main for this website and others. While I was still living in Colorado  on September 21, 2011, I was not in attendance for the Ron Miles concert presented on the posthumous release, “Old Main Chapel“. Ron was a local legend as a progressive jazz trumpeter and educator. By the time of this recording, Ron and I had met but our friendship developed a few years later when we were both working at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Denver. I was a soloist and section leader in the choir, and Ron was pursuing religious studies while helping with the Sunday services. Ron invited me to teach his jazz history students about the wonders of Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. We had several good conversations over the years, and when I moved to Delaware in 2020, I did not realize that Ron’s long-standing illness would prematurely end his life just two years later. Ron was on the Blue Note roster at his death, and this superb concert acts as a fitting eulogy to an underappreciated musician. At this concert, he performed with fellow giants Bill Frisell and Brian Blade, and the psychic interplay between these three musicians can be heard throughout this recording—all the more remarkable since this trio had only existed for about a year. In his touching and informative liner notes, Jason Moran relates that Ron used to hand out his music in full score, so that everyone in the group knew their specific roles. With one exception, Ron composed all of the songs on the program, and many of the titles referred to friends and family. The one standard is a real oldie, “There Ain’t No Sweet Man That’s Worth the Salt of My Tears”. With the combination of an extended Blade solo as an introduction, a slow and sexy tempo, an original riff for Frisell, and an updated harmonic sequence for improvisation, the standard appears in a new guise—still a little nostalgic, but also relevant to today’s jazz. Frisell was one of Ron’s best musical partners, and I love how his improvisation stands on its own merits, but also serves as a prelude to Ron’s towering statement. Ron knew the roots of jazz, and his “Guest of Honor” is an authentic example of modern ragtime composition, and the ample silences built into the piece are just as delightful as the actual notes. If the thought of a 78-minute concert by progressive jazz musicians scares you, I urge you to sample this album on streaming media, and after you hear this accessible music for yourself, then buy the album. I am sorry that I wasn’t at Old Main to hear this music live. However, this recording will continue to remind me of the quiet genius, Ron Miles. Rest in Power, sir.

on September 21, 2011, I was not in attendance for the Ron Miles concert presented on the posthumous release, “Old Main Chapel“. Ron was a local legend as a progressive jazz trumpeter and educator. By the time of this recording, Ron and I had met but our friendship developed a few years later when we were both working at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Denver. I was a soloist and section leader in the choir, and Ron was pursuing religious studies while helping with the Sunday services. Ron invited me to teach his jazz history students about the wonders of Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. We had several good conversations over the years, and when I moved to Delaware in 2020, I did not realize that Ron’s long-standing illness would prematurely end his life just two years later. Ron was on the Blue Note roster at his death, and this superb concert acts as a fitting eulogy to an underappreciated musician. At this concert, he performed with fellow giants Bill Frisell and Brian Blade, and the psychic interplay between these three musicians can be heard throughout this recording—all the more remarkable since this trio had only existed for about a year. In his touching and informative liner notes, Jason Moran relates that Ron used to hand out his music in full score, so that everyone in the group knew their specific roles. With one exception, Ron composed all of the songs on the program, and many of the titles referred to friends and family. The one standard is a real oldie, “There Ain’t No Sweet Man That’s Worth the Salt of My Tears”. With the combination of an extended Blade solo as an introduction, a slow and sexy tempo, an original riff for Frisell, and an updated harmonic sequence for improvisation, the standard appears in a new guise—still a little nostalgic, but also relevant to today’s jazz. Frisell was one of Ron’s best musical partners, and I love how his improvisation stands on its own merits, but also serves as a prelude to Ron’s towering statement. Ron knew the roots of jazz, and his “Guest of Honor” is an authentic example of modern ragtime composition, and the ample silences built into the piece are just as delightful as the actual notes. If the thought of a 78-minute concert by progressive jazz musicians scares you, I urge you to sample this album on streaming media, and after you hear this accessible music for yourself, then buy the album. I am sorry that I wasn’t at Old Main to hear this music live. However, this recording will continue to remind me of the quiet genius, Ron Miles. Rest in Power, sir.

KEN PEPLOWSKI: “LIVE AT MEZZROW” (Cellar/Smalls 7)

When Ken Peplowski‘s newest album “Live at Mezzrow” arrived in my mailbox, I was already planning to catch one of his sets at Birdland, and I thought of combining the reviews of this CD and the live gig at Birdland. My reasons for separating the two reviews are probably clear to anyone who has visited both clubs. Located just off Times Square, Birdland is a fairly spacious club (at least for New York City) with lots of room on stage and in the audience. Mezzrow is a converted speakeasy in Greenwich Village which is roughly the size of a wide hallway. The physical experience of hearing music at Mezzrow is more intimate as the natural sound of the instruments easily fills the room. The constant elements between Peplowski’s sets at the two venues are that the group performs this music for the first time on stage, and—in a quality which necessarily follows—both the leader and the rhythm section work at a uniformly high level throughout the set. Peplowski, who has suffered serious medical issues in the last few years, now plays with a renewed energy (listen to his inspired interplay with drummer Willie Jones III on “Beautiful Love”) and the rhythm section of Ted Rosenthal (piano), Martin Wind (bass) and Jones support the leader with deep swing and subtly shifting dynamics. The quartet deftly maneuvers through unfamiliar material like Hank Jones‘ “Vignette” and finds a fresh, romantic approach to Jerome Kern‘s “All the Things You Are” (the latter with Wind’s gloriously lyric bass matching Peplowski’s rich-toned clarinet exposition). Rosenthal’s solo on “Like Young” is a gem with excellent development of the theme early on, followed by a breathtaking run down the keyboard a few bars later. Jones makes great use of his brushes with a tap-styled solo on his snare in a delightful rendition of “Cabin in the Sky”. The album includes spirited tributes to Thelonious Monk (“Bright Mississippi”) and Duke Ellington (“Who Knows”) but the most surprising entry comes between the two, an instrumental version of the Shirley Horn classic “Here’s to Life”. Peplowski praises the lyrics to both “All the Things” and “Here’s to Life” in his liner notes, but it seems strange to hear these great songs without their remarkable words (perhaps Peplowski might collaborate with Ann Hampton Callaway for an album of standards?) This album is a fine representation of a night with the Ken Peplowski Quartet—and if you want to read about their night at Birdland, read my review here.

When Ken Peplowski‘s newest album “Live at Mezzrow” arrived in my mailbox, I was already planning to catch one of his sets at Birdland, and I thought of combining the reviews of this CD and the live gig at Birdland. My reasons for separating the two reviews are probably clear to anyone who has visited both clubs. Located just off Times Square, Birdland is a fairly spacious club (at least for New York City) with lots of room on stage and in the audience. Mezzrow is a converted speakeasy in Greenwich Village which is roughly the size of a wide hallway. The physical experience of hearing music at Mezzrow is more intimate as the natural sound of the instruments easily fills the room. The constant elements between Peplowski’s sets at the two venues are that the group performs this music for the first time on stage, and—in a quality which necessarily follows—both the leader and the rhythm section work at a uniformly high level throughout the set. Peplowski, who has suffered serious medical issues in the last few years, now plays with a renewed energy (listen to his inspired interplay with drummer Willie Jones III on “Beautiful Love”) and the rhythm section of Ted Rosenthal (piano), Martin Wind (bass) and Jones support the leader with deep swing and subtly shifting dynamics. The quartet deftly maneuvers through unfamiliar material like Hank Jones‘ “Vignette” and finds a fresh, romantic approach to Jerome Kern‘s “All the Things You Are” (the latter with Wind’s gloriously lyric bass matching Peplowski’s rich-toned clarinet exposition). Rosenthal’s solo on “Like Young” is a gem with excellent development of the theme early on, followed by a breathtaking run down the keyboard a few bars later. Jones makes great use of his brushes with a tap-styled solo on his snare in a delightful rendition of “Cabin in the Sky”. The album includes spirited tributes to Thelonious Monk (“Bright Mississippi”) and Duke Ellington (“Who Knows”) but the most surprising entry comes between the two, an instrumental version of the Shirley Horn classic “Here’s to Life”. Peplowski praises the lyrics to both “All the Things” and “Here’s to Life” in his liner notes, but it seems strange to hear these great songs without their remarkable words (perhaps Peplowski might collaborate with Ann Hampton Callaway for an album of standards?) This album is a fine representation of a night with the Ken Peplowski Quartet—and if you want to read about their night at Birdland, read my review here.

LISA RICH: “LONG AS YOU’RE LIVING” (Tritone 3)

Lisa Rich‘s previous CD was “Highwire“, a recording she made in 1987 and finally prepared for release 32 years later. In the interim, Rich was sidelined by medical issues, and she used the delayed release of the album to jumpstart her revitalized career. The long-awaited follow-up, “Long as You’re Living” finds Rich in present tense, with a remarkably flexible voice, superb diction, and an adventurous spirit. Part of the credit for Rich’s rejuvenation must be credited to her friend and producer Jay Clayton, who encouraged her to take chances through improvisation. Rich reunited with Marc Copland and Drew Gress, who played piano and bass on her previous album, but she decided not to use a drummer, which gave the rhythm an open feel. Trumpeter Dave Ballou adds a welcome secondary solo voice on 6 of the 12 tracks. The first two tracks are songs associated with Max Roach (“Long as Your Living”) and Abbey Lincoln (“Throw It Away”). These tracks are great introductions to Rich, with samples of scat singing and vivid storytelling, but the program that follows offers many expansions of these (and other) concepts. The true intimacy of the album becomes apparent in a stunning interpretation of Leslie Bricusse‘s “When I Look in Your Eyes”. Copland does not restrict himself in his intro, presenting ambiguous tonality before Rich enters for an expressive chorus of harmonically-assured melody and highly intense storytelling. Clayton’s “New Morning Blues” inspires playful scatting more reminiscent of an instrumentalist rather than a vocalist. “Highwire” included a version of Ornette Coleman‘s “Lonely Woman”, and for the new recording, Rich performed the other “Lonely Woman”, composed by Horace Silver, with lyrics by Leonard Feather. Making the most out of this solemn ballad, Rich takes the song in a dead-slow rubato to savor every syllable. Her phrases rise and fall with natural dynamics, with tiny peaks inserted to emphasize particular words. The deep sensitivity continues with an intricate piano/bass dialogue before Rich returns for the final theme statement. The next three tracks are instrumental tunes, long considered too difficult to sing. No one told that to Rich, and she sounds fearless on Joe Henderson‘s “Isotope”, Jimmy Rowles‘ “The Peacocks” and Fats Waller‘s “Jitterbug Waltz”. A carefree version of “Close Your Eyes” (with another superb scat solo) precedes another “unsingable” melody, Thelonious Monk‘s “Ask Me Now” and a rendition of “Bye Bye, Blackbird” with its rarely-performed verse. Rich’s scat acknowledges the classic Miles Davis solo in her notes, followed by Ballou’s homage with tones. Saving the most adventurous track for the finale, Rich moves headlong into Clayton’s pointillistic scat style for several minutes of free association improvisation. Eventually, the four musicians segue into a warm version of Erik Satie‘s First Gynopedie. Jay Clayton passed away in 2024, but her star pupil Lisa Rich is back in the recording studio to create a follow-up album. I am sure that Clayton will be there in spirit.

was sidelined by medical issues, and she used the delayed release of the album to jumpstart her revitalized career. The long-awaited follow-up, “Long as You’re Living” finds Rich in present tense, with a remarkably flexible voice, superb diction, and an adventurous spirit. Part of the credit for Rich’s rejuvenation must be credited to her friend and producer Jay Clayton, who encouraged her to take chances through improvisation. Rich reunited with Marc Copland and Drew Gress, who played piano and bass on her previous album, but she decided not to use a drummer, which gave the rhythm an open feel. Trumpeter Dave Ballou adds a welcome secondary solo voice on 6 of the 12 tracks. The first two tracks are songs associated with Max Roach (“Long as Your Living”) and Abbey Lincoln (“Throw It Away”). These tracks are great introductions to Rich, with samples of scat singing and vivid storytelling, but the program that follows offers many expansions of these (and other) concepts. The true intimacy of the album becomes apparent in a stunning interpretation of Leslie Bricusse‘s “When I Look in Your Eyes”. Copland does not restrict himself in his intro, presenting ambiguous tonality before Rich enters for an expressive chorus of harmonically-assured melody and highly intense storytelling. Clayton’s “New Morning Blues” inspires playful scatting more reminiscent of an instrumentalist rather than a vocalist. “Highwire” included a version of Ornette Coleman‘s “Lonely Woman”, and for the new recording, Rich performed the other “Lonely Woman”, composed by Horace Silver, with lyrics by Leonard Feather. Making the most out of this solemn ballad, Rich takes the song in a dead-slow rubato to savor every syllable. Her phrases rise and fall with natural dynamics, with tiny peaks inserted to emphasize particular words. The deep sensitivity continues with an intricate piano/bass dialogue before Rich returns for the final theme statement. The next three tracks are instrumental tunes, long considered too difficult to sing. No one told that to Rich, and she sounds fearless on Joe Henderson‘s “Isotope”, Jimmy Rowles‘ “The Peacocks” and Fats Waller‘s “Jitterbug Waltz”. A carefree version of “Close Your Eyes” (with another superb scat solo) precedes another “unsingable” melody, Thelonious Monk‘s “Ask Me Now” and a rendition of “Bye Bye, Blackbird” with its rarely-performed verse. Rich’s scat acknowledges the classic Miles Davis solo in her notes, followed by Ballou’s homage with tones. Saving the most adventurous track for the finale, Rich moves headlong into Clayton’s pointillistic scat style for several minutes of free association improvisation. Eventually, the four musicians segue into a warm version of Erik Satie‘s First Gynopedie. Jay Clayton passed away in 2024, but her star pupil Lisa Rich is back in the recording studio to create a follow-up album. I am sure that Clayton will be there in spirit.

RENEE ROSNES: “CROSSING PATHS” (Smoke Sessions 2408)

MPB (Música popular brasileira) was an umbrella term coined in 1964 at the end of the bossa nova craze. It encompassed a wide variety of genres, including the new Tropicalia style popularized by Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, and Gilberto Gil, as well as the still-evolving bossa  styles of Tom Jobim, João Gilberto, and Edu Lobo. In her new Brazilian tribute CD, “Crossing Paths“, Renee Rosnes combines a primarily American instrumental ensemble with three of Brazil’s finest vocalists to illustrate the development of MPB. The album opens with a grooving performance of Egberto Gismonti‘s “Frevo” with flutist Shelley Brown and guitarist Chico Pinheiro essaying the theme before yielding to electric bassist John Patitucci‘s dazzling solo. An ensemble background changes into a shout chorus before Rosnes and Pinheiro engage in exchanges and dual improvisation. The next track features Edu Lobo singing his tragic ballad “Pra Dizer Adeus” (later known as “To Say Goodbye”). Lobo’s mature and emotional vocal precedes a tender passage sung and played by Rosnes. Trombonist Steve Davis joins the ensemble for Caetano Veloso’s “Trilhos Urbanos”. The song was written about the tram in Veloso’s hometown of Santo Amaro, and Rosnes’ rhythm section (powered by set drummer Adam Cruz and percussionist Rogério Boccatto) sets a great churning rhythm for this heartfelt tribute. Maucha Adnet sang with Jobim for a decade and her emotional reading of the master’s “Canta Canta Mais” is beautifully supported by a background chorus of Rosnes, Brown, Patitucci, and Boccato (Patitucci also contributes glorious arco bass elsewhere in the arrangement). “Casa Forte” features Lobo again along with the entire ensemble—including the marvelous Chris Potter on soprano and tenor saxes. Lobo’s voice retains the flexibility required to sing his twisting wordless melody, and the breathless solos by Potter, Rosnes, and Davis were inspired by Lobo’s energetic vocals. In her only appearance on the album, Joyce Moreno wrings all of the pent-up emotions from “Essa Mukher,” an ode to modern femininity she composed with Ana Terra. The duet between Rosnes and Moreno at the beginning of the track is one of the highlights of the album, and I wish that a duet track between these two musicians could have been included in the playlist. Potter’s strong tenor lead enlivens Gilberto Gil’s “Amor Até O Fim”, and Pinheiro’s guitar solo grabs the energy and builds. After Davis, Potter dominates with a powerful improvisation, and Rosnes jumps into an inspired solo on the Fender Rhodes. Rosnes’ first exposure to Brazilian music came from the Wayne Shorter/Milton Nascimento album “Native Dancer” and she eventually played some of the music from that album when she was a member of Shorter’s Quartet. Nascimento’s “Estórias da Floresta” comes from a later album “Txai“, and the repeated melody over the churning rhythm evokes the sounds of ancient folk music. The title track (by Jobim and Mendonça) is also the closer, with a heart-rending vocal from Adnet and a flowing piano by the leader. And then, without much warning, this beautiful recital is over—another victim of the short CD running times needed to accommodate a simultaneous vinyl release. When music of this quality is involved (with such incredible musicians bringing their best efforts) why not create a full-length CD and a 2-LP set? There’s so much more good music to be mined from this fertile soil.

styles of Tom Jobim, João Gilberto, and Edu Lobo. In her new Brazilian tribute CD, “Crossing Paths“, Renee Rosnes combines a primarily American instrumental ensemble with three of Brazil’s finest vocalists to illustrate the development of MPB. The album opens with a grooving performance of Egberto Gismonti‘s “Frevo” with flutist Shelley Brown and guitarist Chico Pinheiro essaying the theme before yielding to electric bassist John Patitucci‘s dazzling solo. An ensemble background changes into a shout chorus before Rosnes and Pinheiro engage in exchanges and dual improvisation. The next track features Edu Lobo singing his tragic ballad “Pra Dizer Adeus” (later known as “To Say Goodbye”). Lobo’s mature and emotional vocal precedes a tender passage sung and played by Rosnes. Trombonist Steve Davis joins the ensemble for Caetano Veloso’s “Trilhos Urbanos”. The song was written about the tram in Veloso’s hometown of Santo Amaro, and Rosnes’ rhythm section (powered by set drummer Adam Cruz and percussionist Rogério Boccatto) sets a great churning rhythm for this heartfelt tribute. Maucha Adnet sang with Jobim for a decade and her emotional reading of the master’s “Canta Canta Mais” is beautifully supported by a background chorus of Rosnes, Brown, Patitucci, and Boccato (Patitucci also contributes glorious arco bass elsewhere in the arrangement). “Casa Forte” features Lobo again along with the entire ensemble—including the marvelous Chris Potter on soprano and tenor saxes. Lobo’s voice retains the flexibility required to sing his twisting wordless melody, and the breathless solos by Potter, Rosnes, and Davis were inspired by Lobo’s energetic vocals. In her only appearance on the album, Joyce Moreno wrings all of the pent-up emotions from “Essa Mukher,” an ode to modern femininity she composed with Ana Terra. The duet between Rosnes and Moreno at the beginning of the track is one of the highlights of the album, and I wish that a duet track between these two musicians could have been included in the playlist. Potter’s strong tenor lead enlivens Gilberto Gil’s “Amor Até O Fim”, and Pinheiro’s guitar solo grabs the energy and builds. After Davis, Potter dominates with a powerful improvisation, and Rosnes jumps into an inspired solo on the Fender Rhodes. Rosnes’ first exposure to Brazilian music came from the Wayne Shorter/Milton Nascimento album “Native Dancer” and she eventually played some of the music from that album when she was a member of Shorter’s Quartet. Nascimento’s “Estórias da Floresta” comes from a later album “Txai“, and the repeated melody over the churning rhythm evokes the sounds of ancient folk music. The title track (by Jobim and Mendonça) is also the closer, with a heart-rending vocal from Adnet and a flowing piano by the leader. And then, without much warning, this beautiful recital is over—another victim of the short CD running times needed to accommodate a simultaneous vinyl release. When music of this quality is involved (with such incredible musicians bringing their best efforts) why not create a full-length CD and a 2-LP set? There’s so much more good music to be mined from this fertile soil.

JANIS SIEGEL & YARON GERSHOVSKY: “THE COLORS OF MY LIFE” (Club 44 4173)

In her 50 years as a member of Manhattan Transfer, Janis Siegel maintained an active solo career with a string of outstanding concept albums (with her duets with Fred Hersch and her thrilling organ combo tribute “Friday Night Special” being my particular favorites). Now that we are in the post-Transfer era, Siegel has doubled down in her solo performances, touring all over the world—she was in Dubai for the latest International Jazz Day—and still producing memorable concept albums. The newest addition to her discography is “The Colors of My Life“, a tribute to Cy Coleman co-lead by the Transfer’s longtime pianist and musical director Yaron Gershovsky. The inside cover of the album sports miniature photos of both musicians with Coleman, and from the recorded results, it is clear that both Siegel and Gershovsky share a great love for this music. The rhythm team of Gershovsky, bassist David Finck, and drummer Cliff Almond set a sultry backdrop for Siegel’s sexy delivery of “I’ve Got Your Number”, and the combination of these elements recalls—and enhances—the composer’s hipster persona. The piano solo builds on the growing intensity, and the effect continues through Siegel’s stunning recapitulation, which features scat, melodic variations, and lots of soul. “With Every Breath I Take” was Coleman’s major ballad from his musical “City of Angels“, and Siegel’s sensitive performance brings out the emotions of the lyric while making subtle changes to the melody. Gershovsky’s skills as an accompanist are evident in every bar of this performance. “Playboy’s Theme” has no lyrics, but Siegel and guest vocalist Aubrey Johnson create a great choral background through overdubbing. Gershovsky’s piano swings mightily and the rhythm section (with Boris Kozlov on bass) has a great time with this simple but catchy piece. Far from Frank Sinatra‘s ring-a-ding-ding recording, Siegel’s approach to “Witchcraft” includes mysterious passages that alternate with straight-ahead swing. The co-leaders play the sassy “That’s My Style” as a swinging duet, with each having the chance to let loose and have fun with the material. Gershovsky’s stride piano shakes the studio’s foundation, and Siegel sings an outstanding scat solo. “Without You” from “Will Rogers Follies” sets Siegel’s passionate vocal against the elegant Crosby Street String Quartet. The rubato opening of “The Best is Yet to Come” brings a sense of wonderment to the lyrics, and even when it segues into swing, the unusual 3-over-4 feel lessens the song’s built-in swagger. Yet before the end of the track, Siegel struts with bold confidence. An assertive arrangement, an organ patch on Gershovsky’s synthesizer, and a soulful overdubbed vocal background transform “I’m Gonna Laugh You Right Out of My Life” into an empowering anthem of separation. Another duet, this time on “Why Try to Change Me Now”, maintains the song’s poignant little-girl-lost message. The closing title track was written as a duet in “Barnum“. In the show, P.T. Barnum and his long-suffering wife contrast their views of life in a rich allegory of colors and images. Gershovsky’s arrangement indicates the changes in character through a simple but effective background swap. While I missed the eventual duet between the two voices, the solo version allows the song to be appreciated away from its original setting. What a wonderful and profound tribute to an underappreciated songwriter!

that we are in the post-Transfer era, Siegel has doubled down in her solo performances, touring all over the world—she was in Dubai for the latest International Jazz Day—and still producing memorable concept albums. The newest addition to her discography is “The Colors of My Life“, a tribute to Cy Coleman co-lead by the Transfer’s longtime pianist and musical director Yaron Gershovsky. The inside cover of the album sports miniature photos of both musicians with Coleman, and from the recorded results, it is clear that both Siegel and Gershovsky share a great love for this music. The rhythm team of Gershovsky, bassist David Finck, and drummer Cliff Almond set a sultry backdrop for Siegel’s sexy delivery of “I’ve Got Your Number”, and the combination of these elements recalls—and enhances—the composer’s hipster persona. The piano solo builds on the growing intensity, and the effect continues through Siegel’s stunning recapitulation, which features scat, melodic variations, and lots of soul. “With Every Breath I Take” was Coleman’s major ballad from his musical “City of Angels“, and Siegel’s sensitive performance brings out the emotions of the lyric while making subtle changes to the melody. Gershovsky’s skills as an accompanist are evident in every bar of this performance. “Playboy’s Theme” has no lyrics, but Siegel and guest vocalist Aubrey Johnson create a great choral background through overdubbing. Gershovsky’s piano swings mightily and the rhythm section (with Boris Kozlov on bass) has a great time with this simple but catchy piece. Far from Frank Sinatra‘s ring-a-ding-ding recording, Siegel’s approach to “Witchcraft” includes mysterious passages that alternate with straight-ahead swing. The co-leaders play the sassy “That’s My Style” as a swinging duet, with each having the chance to let loose and have fun with the material. Gershovsky’s stride piano shakes the studio’s foundation, and Siegel sings an outstanding scat solo. “Without You” from “Will Rogers Follies” sets Siegel’s passionate vocal against the elegant Crosby Street String Quartet. The rubato opening of “The Best is Yet to Come” brings a sense of wonderment to the lyrics, and even when it segues into swing, the unusual 3-over-4 feel lessens the song’s built-in swagger. Yet before the end of the track, Siegel struts with bold confidence. An assertive arrangement, an organ patch on Gershovsky’s synthesizer, and a soulful overdubbed vocal background transform “I’m Gonna Laugh You Right Out of My Life” into an empowering anthem of separation. Another duet, this time on “Why Try to Change Me Now”, maintains the song’s poignant little-girl-lost message. The closing title track was written as a duet in “Barnum“. In the show, P.T. Barnum and his long-suffering wife contrast their views of life in a rich allegory of colors and images. Gershovsky’s arrangement indicates the changes in character through a simple but effective background swap. While I missed the eventual duet between the two voices, the solo version allows the song to be appreciated away from its original setting. What a wonderful and profound tribute to an underappreciated songwriter!

THE SWINGLES: “THEATRELAND” (Swingle Singers 33)

In the course of their 63-year history, the Swingle Singers have recorded at least 75 albums, most of which could be tagged as concept  albums. Their latest release, “Theatreland” marks the first time that the group has focused on songs from Broadway musicals. On February 1, 2024, I heard the group at the Keystone Korner in Baltimore as they premiered 7 new arrangements from this project, and my sense of anticipation only increased as the album’s promised release date of Labor Day drew near. By release day, the music was only part of the equation. At the Baltimore engagement, The Swingles’ second tenor and arranger Jon Smith had announced his departure from the Swingles upon the release of “Theatreland”, and over the spring and summer, the news came that three more of the seven Swingles were also planning to leave the group in the fall. The four departing members—Smith, Joanna Goldsmith-Eteson, Midge Perry, and Oliver Griffiths—represented a key creative element of the group. “Theatreland” stands as a summation of the artistic triumphs created by this progressive edition of the Swingles.

albums. Their latest release, “Theatreland” marks the first time that the group has focused on songs from Broadway musicals. On February 1, 2024, I heard the group at the Keystone Korner in Baltimore as they premiered 7 new arrangements from this project, and my sense of anticipation only increased as the album’s promised release date of Labor Day drew near. By release day, the music was only part of the equation. At the Baltimore engagement, The Swingles’ second tenor and arranger Jon Smith had announced his departure from the Swingles upon the release of “Theatreland”, and over the spring and summer, the news came that three more of the seven Swingles were also planning to leave the group in the fall. The four departing members—Smith, Joanna Goldsmith-Eteson, Midge Perry, and Oliver Griffiths—represented a key creative element of the group. “Theatreland” stands as a summation of the artistic triumphs created by this progressive edition of the Swingles.

Programmed into two acts, “Theatreland” packs 24 classic Broadway melodies into 65 minutes. Some of the more familiar songs appear as short interludes, and despite their brevity, they present fine solo opportunities for members of the group, especially the basses Jamie Wright and Tom Hartley who excel on “Edelweiss” and “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face”, respectively. The cheeky Act I finale of “You’ll Be Back” from “Hamilton” turns the main refrain of King George’s vengeful song into a fughetta (which is a natural choice for a group with roots in Bach). Four additional settings feature guest artists Janie Dee (“Send in the Clowns”, with a Ward Swingle chart as backup), Voctave (“I Am What I Am”, a powerful gay anthem featuring a soaring lead vocal from Smith), Roshani Abbey and ChoirCo (“Aquarius” and “Let the Sunshine In”, well-sung, but little more than covers of the original versions). The 7 full-length arrangements premiered in Baltimore—”Wedding Song” from “Hadestown”, “Song of Purple Summer” from “Spring Awakening”, “Grease is the Word” from “Grease”, “A Soft Place to Land” from “Waitress”, “Hear My Song” from “Songs for a New World”, “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ the Boat” from “Guys and Dolls”, and “Sunday” from “Sunday in the Park with George”—form the core music for the album. All of these performances reflect the best attributes of this incredible group: passionate solos, flawless ensembles, and richly scored arrangements. I was especially impressed with the energetic duet of Perry and Griffiths on “Wedding Song”, the glorious mixture of the female voices on Smith’s shimmering arrangement of “A Soft Place to Land”, Smith’s show-stopping turn on Darmon Meader‘s swinging version of “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ the Boat” and Edward Randell‘s austere setting of “Sunday”. “Hear My Song” is simultaneously the most bittersweet and inspiring track on the album. All four of the departing Swingles are featured soloists, and it is hard to imagine how the Swingles will sound without these distinctive voices. But like every other musical ensemble, The Swingles will evolve through the talents and passions of its new members. To quote the lyrics of “Hear My Song”, We’ll be fine.

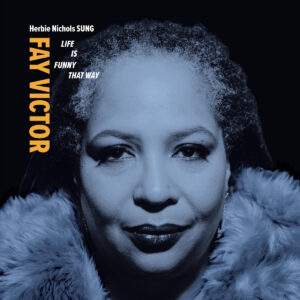

FAY VICTOR/”HERBIE NICHOLS SUNG”: “LIFE IS FUNNY THAT WAY” (TaoForms 15)

Herbie Nichols had ample opportunities as an emerging jazz pianist and composer. He was liked and admired by many of his contemporaries, he had a recording contract with Blue Note, and one of his songs was set to words and performed by Billie Holiday. However, many of his recordings lack energy (partially due to a lack of horns) and while Blue Note producer Alfred Lion stuck with Nichols for three LPs, none of them sold well enough to spur a contract renewal. It was only through the efforts of musicians like Roswell Rudd, Misha Mengelberg, Buell Neidlinger, and Frank Kimbrough that Nichols and his works were remembered after his death. All of those four musicians have now passed, but one of Rudd’s friends, vocalist Fay Victor, decided to revisit Nichols’ music augmented with her original lyrics. “Life is Funny That Way” marks the recording debut of Victor’s band Herbie Nichols SUNG, and it re-energizes Nichols’ music with inventive words and arrangements. The base quartet is introduced piecemeal on the title track (originally titled “Double Exposure”) with Victor performing the melody with alto saxophonist Michaël Attias as an unaccompanied duet. Bassist Ratzo Harris enters on the second half of the chorus with drummer Tom Rainey coming in just before Victor launches into an adventurous scat solo. Built on the models of Betty Carter, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Sarah Vaughan, and Carmen McRae, Victor’s style has a wider harmonic imagination which keeps her ideas distinct and progressive. The quartet’s interplay is unpredictable as it leads into territories rarely explored on vocal albums. “The Bassist” (“The Gig”) ironically drops Harris out of the group—the lyrics are about a bassist who fails to show up for the job—but the trio manages very well despite his temporary absence. Nichols never recorded his “Another Friend”, but it appeared on several Nichols tribute albums featuring pianist David Haney. Victor’s lyric changes the title to “Bright Butterfly” and the performance has an ethereal beauty with Victor’s passionate vocal set against Harris’ arco bass and Attais’ improvised commentary. “The Happenings” was originally an unissued title from Nichols’ sole session for Bethlehem. The vocal version “Sinners, All of Us!” is a portrait of a tent-show evangelist, with the dirge tempo of Charles Mingus‘ “Fables of Faubus” inserted to add deeply sardonic humor. Pianist Anthony Coleman joins the group starting on “The Culprit is You”, which transforms Nichols’ “2300 Skidoo” into a completely new—and utterly fascinating—creation before the original is revealed in the final chorus. The first half closes with a spirited quintet jam on “Shuffle Montgomery”. No words are added for this track, but Attais wails on baritone, Victor scats with vigor, and the full rhythm section swings powerfully. The second half contains many delightful moments including “Tonight”, which is a sassy remake of “House Party Starting” featuring Victor’s exceptional lyrics and scatting, a Monkish solo from Coleman, and an expansive baritone statement from Attais; a tortured reading of “Lady Sings the Blues” performed in free tempo; a brief performance of “Twelve Bars” displaying an avant-garde piano trio far removed from Nichols’ conception; an eerie journey to a mental breakdown on “Descent into Madness” (aka “The Spinning Song”); and an exciting free-for-all on “Non-Fraternization Clause” (“Step Tempest”). If Herbie Nichols had his compositions recorded with as much energy and spirit as on “Life is Funny That Way”, he would have been more successful in his time, and remembered by more people today. Let Herbie Nichols’ spirit rise!

with inventive words and arrangements. The base quartet is introduced piecemeal on the title track (originally titled “Double Exposure”) with Victor performing the melody with alto saxophonist Michaël Attias as an unaccompanied duet. Bassist Ratzo Harris enters on the second half of the chorus with drummer Tom Rainey coming in just before Victor launches into an adventurous scat solo. Built on the models of Betty Carter, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Sarah Vaughan, and Carmen McRae, Victor’s style has a wider harmonic imagination which keeps her ideas distinct and progressive. The quartet’s interplay is unpredictable as it leads into territories rarely explored on vocal albums. “The Bassist” (“The Gig”) ironically drops Harris out of the group—the lyrics are about a bassist who fails to show up for the job—but the trio manages very well despite his temporary absence. Nichols never recorded his “Another Friend”, but it appeared on several Nichols tribute albums featuring pianist David Haney. Victor’s lyric changes the title to “Bright Butterfly” and the performance has an ethereal beauty with Victor’s passionate vocal set against Harris’ arco bass and Attais’ improvised commentary. “The Happenings” was originally an unissued title from Nichols’ sole session for Bethlehem. The vocal version “Sinners, All of Us!” is a portrait of a tent-show evangelist, with the dirge tempo of Charles Mingus‘ “Fables of Faubus” inserted to add deeply sardonic humor. Pianist Anthony Coleman joins the group starting on “The Culprit is You”, which transforms Nichols’ “2300 Skidoo” into a completely new—and utterly fascinating—creation before the original is revealed in the final chorus. The first half closes with a spirited quintet jam on “Shuffle Montgomery”. No words are added for this track, but Attais wails on baritone, Victor scats with vigor, and the full rhythm section swings powerfully. The second half contains many delightful moments including “Tonight”, which is a sassy remake of “House Party Starting” featuring Victor’s exceptional lyrics and scatting, a Monkish solo from Coleman, and an expansive baritone statement from Attais; a tortured reading of “Lady Sings the Blues” performed in free tempo; a brief performance of “Twelve Bars” displaying an avant-garde piano trio far removed from Nichols’ conception; an eerie journey to a mental breakdown on “Descent into Madness” (aka “The Spinning Song”); and an exciting free-for-all on “Non-Fraternization Clause” (“Step Tempest”). If Herbie Nichols had his compositions recorded with as much energy and spirit as on “Life is Funny That Way”, he would have been more successful in his time, and remembered by more people today. Let Herbie Nichols’ spirit rise!