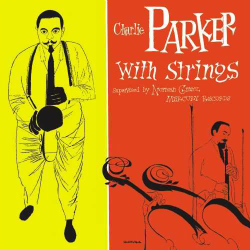

The exclusive recording contract between Charlie Parker and Norman Granz was beneficial to both parties. Granz had just started his Clef label in cooperation with Mercury Records, and signing Parker was a coup for the young producer. Granz did not yet have his larger roster of recording artists when Parker signed on sometime in late 1948, and Parker seemed willing to record sides with groups other than his working quintet. In fact, Parker already got a sense of this variety when he recorded two sides for Granz’s album “The Jazz Scene” in December 1947: For “The Bird”, recorded at Carnegie Hall’s recital studio, he was paired with the exceptional trio of Hank Jones, Ray Brown and Shelly Manne, and then he went over to the main concert hall to sit in with Neal Hefti’s large orchestra on “Repetition”. Parker also worked side-by-side with swing musicians—including his idol Lester Young—on Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts. The JATP and “Jazz Scene” recordings were all apparently one-off affairs, so when Parker actually started his exclusive contract, it was on a recording with Machito and his mambo orchestra. There was another JATP live concert and a couple of combo dates recorded before Parker realized a long-held dream: Charlie Parker with Strings. Here was his opportunity to play standards (his earlier recording companies were loath to record standards because of royalties) and to work in a group vastly different than anything he had performed with in the past. The critics all screamed that it was commercialism, and to an extent it was. But Parker’s recordings with strings were also an artistic success to a certain degree. Nearly a CDs worth of alternate takes from these sessions have just been released along with the well-known master takes in a new double CD set from Verve, “Charlie Parker with Strings: Deluxe Edition” (Verve has wisely avoided the word “complete” in the album title: most of the alternates are released here for the first time, and thus are not on the 10-CD box set “Bird: The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve“).

The exclusive recording contract between Charlie Parker and Norman Granz was beneficial to both parties. Granz had just started his Clef label in cooperation with Mercury Records, and signing Parker was a coup for the young producer. Granz did not yet have his larger roster of recording artists when Parker signed on sometime in late 1948, and Parker seemed willing to record sides with groups other than his working quintet. In fact, Parker already got a sense of this variety when he recorded two sides for Granz’s album “The Jazz Scene” in December 1947: For “The Bird”, recorded at Carnegie Hall’s recital studio, he was paired with the exceptional trio of Hank Jones, Ray Brown and Shelly Manne, and then he went over to the main concert hall to sit in with Neal Hefti’s large orchestra on “Repetition”. Parker also worked side-by-side with swing musicians—including his idol Lester Young—on Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts. The JATP and “Jazz Scene” recordings were all apparently one-off affairs, so when Parker actually started his exclusive contract, it was on a recording with Machito and his mambo orchestra. There was another JATP live concert and a couple of combo dates recorded before Parker realized a long-held dream: Charlie Parker with Strings. Here was his opportunity to play standards (his earlier recording companies were loath to record standards because of royalties) and to work in a group vastly different than anything he had performed with in the past. The critics all screamed that it was commercialism, and to an extent it was. But Parker’s recordings with strings were also an artistic success to a certain degree. Nearly a CDs worth of alternate takes from these sessions have just been released along with the well-known master takes in a new double CD set from Verve, “Charlie Parker with Strings: Deluxe Edition” (Verve has wisely avoided the word “complete” in the album title: most of the alternates are released here for the first time, and thus are not on the 10-CD box set “Bird: The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve“).

The opening track, “Just Friends” was Parker’s biggest hit of his career, and a recording that Parker considered one of his best (he reportedly played it for the doctor who treated him during his final days at Baroness Nica de Koenigswarter’s apartment). It’s hard to argue: after the glossy string and harp introduction, Parker’s rich sound fills the speakers. The mix between alto and strings is perfect from the start, and after Mitch Miller’s oboe interlude, Parker improvises a brilliant solo that is quite melodic and accessible. To top it off, this odd collection of instruments finds a coherent ensemble sound immediately and the performance actually swings! The alternates offer conclusive evidence that Parker was indeed improvising throughout these sessions, and from time to time, the arrangements are modified to offer greater contrasts between the strings and Parker. Had they continued making tracks like “Just Friends”, the whole Parker with Strings concept might have been accepted. Instead (probably right after finishing the master of “Just Friends”), someone must have said “Bird, can you play some more melody in your solos?” and for some reason, Parker agreed, for there are few pure improvisations in the succeeding tracks “Everything Happens to Me”, “April in Paris” and “Summertime”. Now, Parker embellishing the melody isn’t necessarily a bad thing—just as on “Clifford Brown with Strings”, the glorious tone of the horn against the string background is quite pleasing in its own right. On these sides, Parker is filling the role of a singer, especially on “Summertime” where the arrangement is a near-copy of the original setting used in the opera “Porgy and Bess”. But when Parker just blows on the chords, as on “If I Should Lose You” and “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was”, the jazz content soars and Parker lifts the whole bandstand with it. And so it goes throughout the set, with the listener hoping for fresh solos, but sometimes having to be content with Parker’s sound and melodic embellishments.

The new Verve set includes both of the Parker with Strings studio sessions, plus a splendid live set from Carnegie Hall which features a new Jimmy Mundy arrangement of “Easy to Love”, plus fine versions of “What is This Thing Called Love”, Gerry Mulligan’s “Rocker” and “Repetition”. The original version of “Repetition” is here too, along with a 1952 big band-and-strings session. The master takes all appear on the first disc, with the alternates all on the second disc. It’s hard to imagine why Verve chose to program the set in this manner. After all, the single-disc “Master Takes” version is still available, so those who don’t care about the alternates can just buy that CD. Those who want to hear the alternate and masters in session order must either program the discs on a CD changer (with the inevitable delays as the machine shifts back and forth between discs) or rip the entire set onto their computer and then create a playlist—or just buy the download. The booklet includes instructions for programming in session order, but somehow they left out “They Can’t Take That Away From Me”. And on the subject of the booklet, it is a mess. Phil Schaap’s fragmentary notes on the alternates list different recording dates than in the main personnel listings. There are also discrepancies regarding the musicians (it is Roy Haynes, not Buddy Rich, on the live Carnegie set, and Stan Freeman plays piano on the first studio session, while Bernie Leighton, plays on the second studio date). Some of the alternates have no commentary at all. Schaap’s sloppy research and attention to all of the wrong details plagued Verve and Columbia reissues for years before those companies stopped hiring him; why he was brought back to Verve for this project is beyond me.

In his later years, Parker expressed an interest in exploring further mixtures between the classical and jazz worlds. Specifically, he mentioned setting his alto against a background of woodwinds, harp, chorus and rhythm section. To Granz’s credit, he recorded Parker with such a group arranged and conducted by Gil Evans. Unfortunately, there were both artistic and technical problems with the recording, and although Parker, Evans and choral director Dave Lambert were apparently willing to remake the session for free, Granz did not want to spend any more time or money on the project. Had Parker lived long enough, he might have become a part of the Third Stream movement and created something entirely new to the jazz and classical worlds. Instead, it was Parker’s former sideman, Miles Davis, who created some of the first stirrings in the Third Stream world with his solos on John Lewis’ “Three Little Feelings” (and like Parker, Davis had to move to a new recording company—Columbia—for the opportunity to make such large-scale recordings). Still, Parker’s recordings with strings were a necessary first step, and in their best moments, they show that the classical and jazz worlds could indeed find common ground.