CECILIA COLEMAN: “OH BOY!” (PandaKat 9801)

A Californian native currently living in New York, pianist/composer Cecilia Coleman says she never thought about forming a big band. She had always played in small groups and has recorded six CDs as leader—but with the release of her new CD, “Oh Boy” she proves that she is not only a fine bandleader, but is a visceral, exciting and original arranger as well. One member of the band, trombonist Sam Burtis says: “Cecilia’s music hangs together in much the s ame way a dream does. I mean, nothing truly ordinary ever happens in dreams, yet in the end they always seem to make a sort of perfect sense. Dream sense. Her music is like that.”

ame way a dream does. I mean, nothing truly ordinary ever happens in dreams, yet in the end they always seem to make a sort of perfect sense. Dream sense. Her music is like that.”

“Liar, Liar,” an adroit, dexterous arrangement, opens the album with a playfully menacing rhythm intro that sets up the up-tempo, boppish theme. The burning solos that follow are by Stan Killian on tenor and Frank Basile on baritone. Among the other tracks are “Dance,” an energetic minor theme with a Latin feel, which features Stephan Kammerer on alto and John Eckert on trumpet, and “Pearl,” a jazz waltz, that offers solos by altoist Bobby Porcelli and trumpeter Kerry MacKillop. “Pearl” also includes a brief, gently skipping interlude by Coleman, which leads to an ear-perking, unexpected sustained major chord at the end. The title tune, “Oh Boy!” has the full band introducing the sassy theme, then a swinging trombone solo by Sam Burtis, driven by Jeff Brillinger’s cymbals and punchy backgrounds from the band, followed by Brainin’s soprano sax and a drum solo by Brillinger. “Princess” is a pretty 3/4 ballad introduced by various blends of the horn sections, and features a flugelhorn solo by MacKillop followed by Burtis on trombone. “#1” is a lively bluesy number in 6/4 over a baritone sax vamp that shifts into a up-tempo 4/4 with a smashing trombone solo by Mike Fahn followed by Geoff Vidal on tenor. Coleman introduces “Because” with an unaccompanied segment of “Danny Boy” and then moves into a rousing Americana-style theme for full band, with solos by Porcelli and Vidal. Most of Coleman’s work eschews song form and instead focuses on statements from the various horn sections, which she expertly weaves together in highly individual tapestries on this thoroughly satisfying debut.

SATOKO FUJII/NATSUKI TAMURA: “MUKU” (Libra 102-031)

Pianist Satoko Fujii and trumpeter Natsuki Tamura have worked together in many different settings, from big band to art rock quartets to small groups, and hav e just released two new CDs, the group disc “Forever” and the duo album “Muku,” These discs continue to explore new sounds and improvisations, and the focus is more introspective and impressionistic that some of their previous work, in particular their intense and jazz-oriented, 2008 recording, “Chun”. The piano trumpet duo album, “Muku,” opens with “Dune and Star,” a moody minor theme with Tamura’s sparse melodic statements over Fujii’s drone-like chords, followed by her own darkly delicate solo. The title tune is a dreamy, melodic ballad that opens with Fujii playing gently and sweetly. Tamura then harmonizes with the melody, and solos sensitively over Fujii’s piano. “Galvanic” creates visual images that could work for a film score, with stabbing, screeching notes, short phrases and sense of urgency and suspense. Similarly, “Patrol” is a humorously sinister theme that would be apt for the opening of a TV mystery show. “In Paris, In February” begins with a pretty trumpet melody, subtly supported by the piano, which leads into a jaunty, rhythmical exchange, and then the piano tip-toes under the trumpet’s responses.

e just released two new CDs, the group disc “Forever” and the duo album “Muku,” These discs continue to explore new sounds and improvisations, and the focus is more introspective and impressionistic that some of their previous work, in particular their intense and jazz-oriented, 2008 recording, “Chun”. The piano trumpet duo album, “Muku,” opens with “Dune and Star,” a moody minor theme with Tamura’s sparse melodic statements over Fujii’s drone-like chords, followed by her own darkly delicate solo. The title tune is a dreamy, melodic ballad that opens with Fujii playing gently and sweetly. Tamura then harmonizes with the melody, and solos sensitively over Fujii’s piano. “Galvanic” creates visual images that could work for a film score, with stabbing, screeching notes, short phrases and sense of urgency and suspense. Similarly, “Patrol” is a humorously sinister theme that would be apt for the opening of a TV mystery show. “In Paris, In February” begins with a pretty trumpet melody, subtly supported by the piano, which leads into a jaunty, rhythmical exchange, and then the piano tip-toes under the trumpet’s responses.

GATO LIBRE: “FOREVER” (Libra 104-030)

The Gato Libre release, “Forever,” is their fifth release since 2005. The group features Tamura on trumpet, Kazuhiko Tsumura on guitar, Fujii on accordion,  and Norikatsu Koreyasu on bass. Koreyasu died in 2011, and these were his final recordings with the group. The pieces are low-key, for the most part, and a number of them use a bass drone as a foundation for the development of solos and interactions among the players. The opener, “Moor,” is a blues of sorts, while “Court” offers an eerie theme and a sensitive accordion solo. “Hokkaido,” one of the “drone” pieces, has Tsumura creating melodic and harmonic interest with an angular solo, quietly accompanied by Koreyasu. On “Japan,” the trumpet and accordion hold single notes while the guitar dances around them. We get our last chance to hear Koreyasu’s beautifully bowed bass on “Waseda” and “World.” In all of Fujii and Tamura’s work here, composition and improvisation seem to melt into one. Interaction, affinity, creatively, and intense listening are what makes their music work.

and Norikatsu Koreyasu on bass. Koreyasu died in 2011, and these were his final recordings with the group. The pieces are low-key, for the most part, and a number of them use a bass drone as a foundation for the development of solos and interactions among the players. The opener, “Moor,” is a blues of sorts, while “Court” offers an eerie theme and a sensitive accordion solo. “Hokkaido,” one of the “drone” pieces, has Tsumura creating melodic and harmonic interest with an angular solo, quietly accompanied by Koreyasu. On “Japan,” the trumpet and accordion hold single notes while the guitar dances around them. We get our last chance to hear Koreyasu’s beautifully bowed bass on “Waseda” and “World.” In all of Fujii and Tamura’s work here, composition and improvisation seem to melt into one. Interaction, affinity, creatively, and intense listening are what makes their music work.

FRED HERSCH: “ALIVE AT THE VANGUARD” (Palmetto 2159)

Fred Hersch’s double CD, “Alive at the Vanguard” is a personal as well as an artistic triumph. Going a step beyond his excellent previous release, “Whirl,” Hersch has proven not only that he is capable of rising above the most drastic physical challenges, but that those very challenges have caused him to develop an even more original, captivating approach to his music. For those who may not know, Hersch was in a two-month coma as a result of AIDS. On this date, Hersch and his trio, bassist John Hébert and drummer Eric McPherson, tackle four standards, seven jazz tunes and seven new compositions by Hersch.

Among the selections a re “Segment,” Charlie Parker‘s only piece in a minor key, a nifty bop tune that gets a cooking treatment by Hersch and company. At one point, Hersch plays a repetitive riff in his right hand and his left hand marches in with its own peremptory melody, as if to say, “Hey, listen to me!” Hersch goes on to finish his inventive, two-fisted improvisation and then back to the theme. “Tristesse,” a stunning tribute to late drummer Paul Motian, is a slow, mournful ballad. Hersch tackles the melody beautifully with both hands, with Hébert hovering below and MacPherson accenting with the brushes. “Dream of Monk,” a quirky, playful, very Monkish theme, is from Hersch’s jazz theater piece “My Coma Dreams”. He says of it: “In this dream, Monk and I are in separate cages in a room; a man bursts into the room, gives us music paper and pencils and says, ‘Whoever can finish a tune first will be released!’ I scribble like mad, finish my tune and I look over at Monk who is just in his cage, sweetly smiling.” “Jackalope,” with its repetitive bass vamp and a chug-a-lug rhythm, actually brings to mind the jackalope of Hersch’s imagination—a mythical creature, half-jackrabbit, half-antelope.

re “Segment,” Charlie Parker‘s only piece in a minor key, a nifty bop tune that gets a cooking treatment by Hersch and company. At one point, Hersch plays a repetitive riff in his right hand and his left hand marches in with its own peremptory melody, as if to say, “Hey, listen to me!” Hersch goes on to finish his inventive, two-fisted improvisation and then back to the theme. “Tristesse,” a stunning tribute to late drummer Paul Motian, is a slow, mournful ballad. Hersch tackles the melody beautifully with both hands, with Hébert hovering below and MacPherson accenting with the brushes. “Dream of Monk,” a quirky, playful, very Monkish theme, is from Hersch’s jazz theater piece “My Coma Dreams”. He says of it: “In this dream, Monk and I are in separate cages in a room; a man bursts into the room, gives us music paper and pencils and says, ‘Whoever can finish a tune first will be released!’ I scribble like mad, finish my tune and I look over at Monk who is just in his cage, sweetly smiling.” “Jackalope,” with its repetitive bass vamp and a chug-a-lug rhythm, actually brings to mind the jackalope of Hersch’s imagination—a mythical creature, half-jackrabbit, half-antelope.

“The Song is You”/”Played Twice” is a whimsical, childlike two-handed melodic interplay. On this pairing and other tunes, Hersch’s hands seem to love each other—they’re like best friends or soulmates. He takes “The Song is You” at a fairly slow tempo, setting it apart from many other jazz interpretations of the standard. “Played Twice” is one of Thelonious Monk’s lesser-known tunes. Hersch’s joining of Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman” with Miles Davis’ ethereal “Nardis,” a medley previously recorded on Hersch’s 90s album “Evanessence,” opens with percussion and a bass pedal that lead into Hersch’s sparse statement of Coleman’s moody theme. A brief bass interlude with percussion bring in the “Nardis” theme, after which the trio leaves the song form in the dust and improvises over free bass and percussion that gradually pick up speed, with Hersch skipping over it all with madcap runs and jabbing punctuations. Finally he does a brilliant fade-out into Hébert’s probing bass solo, and takes it out, after restating the “Lonely Woman” theme, with a fistful of cascading chords. Among some of the other tunes here are an engaging, bluesy, slow rendition of the Sonny Rollins standard “Doxy;” “Sartorial (for Ornette), a totally free-bag, joyous romp and a tribute to Coleman’s fashion sense; and a 5/4 bossa nova version of the standard “From This Moment On.” On this live set, Hersch is spontaneous, carefree, often humorous, even devil-may-care, and also forceful and authoritative. He plays with complete freedom of expression—whatever comes to mind, out it comes, with no regard for rules or conventions. He is currently one of jazz’s most refreshing creators.

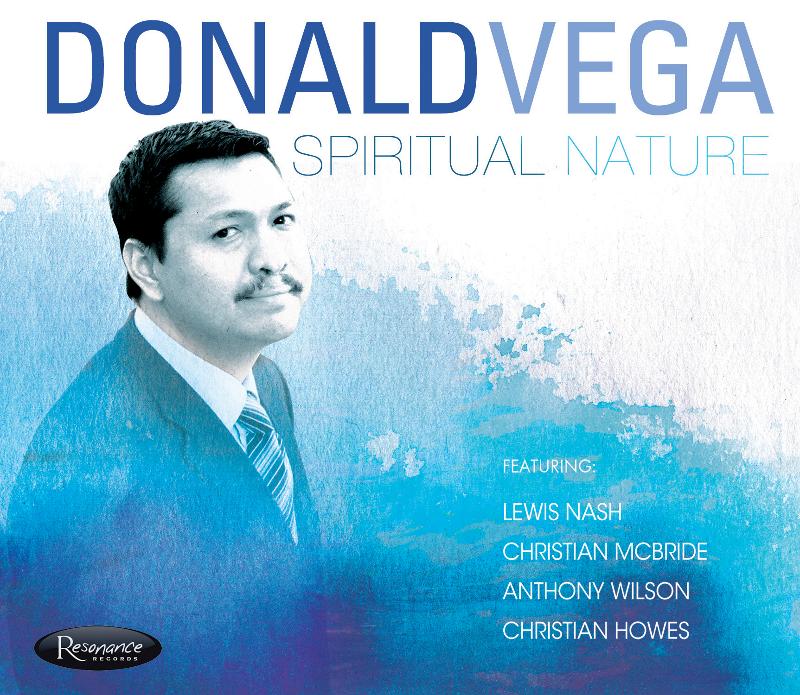

DONALD VEGA: “SPIRITUAL NATURE” (Resonance 1019)

In “Spiritual Nature”, his debut recording for Resonance Records pianist/composer Donald Vega mixes jazz, classical and Latin styles in three different settings: trio, quartet and quintet. Vega, who was born in Nicaragua and grew up in Los Angeles from age 14, learned jazz from his mentor, drummer Billy Higgins. He is now gaining media attention as Mulgrew Miller’s replacement in the Ron Carter Trio. The album opens with the hard bop number “Scorpion,” featuring trumpeter Gilbert Castellanos and tenor saxophonist Bob Sheppard. After the horn solos, we’re treated to a forceful, articulate solo by Vega, sensitively accompanied by Lewis Nash and Christian McBride, which builds over backgrounds by the horns. Ron Carter’s tune, “First Trip,” highlights Nash’s drums while Anthony Wilson and McBride get in some swinging licks on guitar and bass, respectively. “The River” introduces violinist Christian Howes, one of the pleasantest surprises on the album. He plays the soaring melody beautifully over a subtle bossa nova beat, and weaves his own special magic on an exquisite solo. The title song, “Spiritual Nature,” is a laid back bossa for the quintet, featuring Sheppard, Castellanos and virtuoso trombonist Bob McChesney. Fleet-fingered Wilson burns on Monty Alexander’s up-tempo “Accompong,” both on his own solo and in a back-and-forth chat with Vega’s piano.

Carter’s tune, “First Trip,” highlights Nash’s drums while Anthony Wilson and McBride get in some swinging licks on guitar and bass, respectively. “The River” introduces violinist Christian Howes, one of the pleasantest surprises on the album. He plays the soaring melody beautifully over a subtle bossa nova beat, and weaves his own special magic on an exquisite solo. The title song, “Spiritual Nature,” is a laid back bossa for the quintet, featuring Sheppard, Castellanos and virtuoso trombonist Bob McChesney. Fleet-fingered Wilson burns on Monty Alexander’s up-tempo “Accompong,” both on his own solo and in a back-and-forth chat with Vega’s piano.

Niels Henning Orsted Pedersen‘s “Future Child” is a gentle waltz that gradually builds into a forceful swinger and reveals Vega’s sensitivity as well as his penchant for creating melodic lines in his improvisations. Makoto Ozone‘s funky modal “You Never Tell Me Anything” is a cooker through and through, with Vega’s boppish lines chugging along in a relaxed, finger-snapping groove. “Contemplation,” an atmospheric ballad, is a conversation between McBride and Vega, with the pianist offering subtle touches on Fender Rhodes. The classically-trained Vega is right at home on Scriabin’s “Etude Opus 8, #2,” which he transforms into a 6/8 feel in the bass, accompanied by Howes’s splendid violin to create a perfect marriage between the classical and Latin idioms. The final track gives us a great introduction to Vega’s approach to the piano in “Falando de Amor–Tema de Amor,” a lovely melody overdubbed three times, in the tradition of Bill Evans’ “Conversations with Myself.” On this album, Vega shows himself to be versatile and imaginative and it will be interesting to see what he comes up with on his next album.