It always bothers me when I see a vocal album that lists the instrumentalists under the banner “Musicians”. After all, isn’t the singer a musician, too? Well, not always. There are plenty of horror stories about professional singers who don’t know the keys and harmonies of their repertoire. However, those mediocre singers are being eclipsed by well-educated vocalists with strong music theory backgrounds and deep knowledge of jazz, pop and classical styles. Many of these singers write their own music and arrangements. And since they know the rules, they know how to break them. The five vocalists discussed here have strong roots in straight-ahead jazz, but their albums find them stretching the accepted boundaries of the music.

Clare Wheeler is best known as the alto from the current edition of the Swingle Singers. She has contributed several fine compositions and arrangements to the Swingle repertoire. On a trip to Denver in September 2010, Wheeler collaborated with composer/arranger Tyler Gilmore to record and perform music that allowed her to stretch beyond her role with the Swingles. Six of those pieces are now available as a digital download album called “Crossing”. With the exception of the opening track, Hanne Hukkelberg’s “Do Not as I Do” (arranged by Gilmore), all of the music was composed by Wheeler or Gilmore. They are set for saxophone quartet and a guitar/bass/drums rhythm section, and the style is progressive and challenging, yet still accessible. With the interweaving lines of the horns, the turbulent nature of the rhythm, and the demanding parts for the vocalist, the music reminds me of the big band collaborations of Norma Winstone and Kenny Wheeler, and of “Five Housman Settings”, a suite written by five British composers for vocalist Jacqui Dankworth and the third stream ensemble New Perspectives. On the present recording, all of the saxophonists–Art Bouton, Wil Swindler, Peter Sommer and Mark Harris—double on clarinets, play as a classical-styled quartet with straight tone, and play improvised solos. The vocal line of Wheeler’s “Valentine” features wide melodic leaps and complex lyrics, and Wheeler performs a daring scat solo over unusual chord changes. The central tracks, “Compensation” and “We Wear the Mask”, are Gilmore setting of Paul Laurence Dunbar poems. They call for Wheeler to sing angular unison lines with Steve Kovalcheck’s guitar, while emphasizing the dramatic texts of the poetry. On “Mask”, Wheeler’s highly personalized reading of the text over the rippling sax lines is extremely intense, but it is very difficult to understand the words amidst all of the instrumental sound. Wheeler’s “Songs and Fables” offers a respite from the intensity with long wordless sections that pair her voice with Swindler’s rich soprano sax. The uplifting closing track, “This Kind of Day” features a soaring ensemble passage with Wheeler and the saxes playing off Sommer’s tenor solo. The album can be downloaded here, and purchasers are free to pay whatever price they’d like for the music.

and perform music that allowed her to stretch beyond her role with the Swingles. Six of those pieces are now available as a digital download album called “Crossing”. With the exception of the opening track, Hanne Hukkelberg’s “Do Not as I Do” (arranged by Gilmore), all of the music was composed by Wheeler or Gilmore. They are set for saxophone quartet and a guitar/bass/drums rhythm section, and the style is progressive and challenging, yet still accessible. With the interweaving lines of the horns, the turbulent nature of the rhythm, and the demanding parts for the vocalist, the music reminds me of the big band collaborations of Norma Winstone and Kenny Wheeler, and of “Five Housman Settings”, a suite written by five British composers for vocalist Jacqui Dankworth and the third stream ensemble New Perspectives. On the present recording, all of the saxophonists–Art Bouton, Wil Swindler, Peter Sommer and Mark Harris—double on clarinets, play as a classical-styled quartet with straight tone, and play improvised solos. The vocal line of Wheeler’s “Valentine” features wide melodic leaps and complex lyrics, and Wheeler performs a daring scat solo over unusual chord changes. The central tracks, “Compensation” and “We Wear the Mask”, are Gilmore setting of Paul Laurence Dunbar poems. They call for Wheeler to sing angular unison lines with Steve Kovalcheck’s guitar, while emphasizing the dramatic texts of the poetry. On “Mask”, Wheeler’s highly personalized reading of the text over the rippling sax lines is extremely intense, but it is very difficult to understand the words amidst all of the instrumental sound. Wheeler’s “Songs and Fables” offers a respite from the intensity with long wordless sections that pair her voice with Swindler’s rich soprano sax. The uplifting closing track, “This Kind of Day” features a soaring ensemble passage with Wheeler and the saxes playing off Sommer’s tenor solo. The album can be downloaded here, and purchasers are free to pay whatever price they’d like for the music.

On Philadelphia vocalist Kaylé Brecher‘s album, “Spirals and Lines”. the backing brass ensemble and guitar/piano /drums rhythm team are led by Jimmy Parker. Parker covers all the bass lines on the album on sousaphone, and this unique choice of bass instruments is a good match for Brecher’s quirky voice. Brecher has some strange vocal habits and her scat syllables are unorthodox, but her voice is quite compelling in this context. The repertoire is highly political including the pro-labor song “High Flying Bird”, a melancholy version of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” and a gospel-like rendition of Lewis Allen’s “The House I Live In”. She arranged all of the pieces on the album, and her brilliant transformation of Bob Dylan’s folk anthem, “Paths of Victory” into a swinging New Orleans march for voice, sousaphone and drums is one of the album’s highlights. Yip Harburg’s Depression-era standard “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime” is set for the same trio, and Brecher’s reading reveals a deep understanding of the song’s harmony. The longest cut is Charles Mingus’ “Noddin’ Ya Head Blues” (originally “White Collar Blues”, here outfitted with lyrics by former JHO contributor Ellen Johnson). Brecher’s chart was designed as a tribute to the original instrumental version, and her scat solo—more than the instrumental solos that surround it—hints at a more sophisticated chord structure than is played by the rhythm section. Brecher also wrote three originals for the album, including the title track, “Will of the Wind” and “So It Goes”. Each of these pieces features her original lyrics (reprinted in the album liners) and prickly wide-ranging melodies sung by Brecher with uncanny accuracy.

/drums rhythm team are led by Jimmy Parker. Parker covers all the bass lines on the album on sousaphone, and this unique choice of bass instruments is a good match for Brecher’s quirky voice. Brecher has some strange vocal habits and her scat syllables are unorthodox, but her voice is quite compelling in this context. The repertoire is highly political including the pro-labor song “High Flying Bird”, a melancholy version of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” and a gospel-like rendition of Lewis Allen’s “The House I Live In”. She arranged all of the pieces on the album, and her brilliant transformation of Bob Dylan’s folk anthem, “Paths of Victory” into a swinging New Orleans march for voice, sousaphone and drums is one of the album’s highlights. Yip Harburg’s Depression-era standard “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime” is set for the same trio, and Brecher’s reading reveals a deep understanding of the song’s harmony. The longest cut is Charles Mingus’ “Noddin’ Ya Head Blues” (originally “White Collar Blues”, here outfitted with lyrics by former JHO contributor Ellen Johnson). Brecher’s chart was designed as a tribute to the original instrumental version, and her scat solo—more than the instrumental solos that surround it—hints at a more sophisticated chord structure than is played by the rhythm section. Brecher also wrote three originals for the album, including the title track, “Will of the Wind” and “So It Goes”. Each of these pieces features her original lyrics (reprinted in the album liners) and prickly wide-ranging melodies sung by Brecher with uncanny accuracy.

Vocal/piano duets are nothing new in jazz, but when the artists are Sara Serpa and Ran Blake, the predictable elements disappear. Serpa is one of the finest vocalists of her generation. Her flexible voice can conjure vivid aural pictures and her improvisations rival the most adventurous jazz instrumentalists. Blake’s unusual manner of accompanying with sudden fortissimo bursts and dense complex chords might seem to be anathema to a vocalist, but he and Serpa align their vivid musical imaginations to transform classic songs into intense dramatic experiences. “Aurora”, recorded in Lisbon in May 2012, is the second collaboration between Serpa and Blake, and it expands on the territory they explored on the album, “Camera Obscura”. Here, the selections are longer and there is a greater emphasis on the texts. With a charming Portuguese accent and a pure vibratoless voice, Serpa might initially remind listeners of Astrud Gilberto, but her interpretations reveal a much deeper understanding of the music’s subtext. Consider Serpa’s unaccompanied version of “Strange Fruit”: unlike Billie Holiday, Serpa has no first-hand experience with lynchings, but her stark reading with precise declamations of the key words and subtly nuanced dynamics emits an eerie atmosphere that evokes those tragic events. While the prevailing mood of the album is dark and intense, there are lighter moments, including a delightful version of the Chris Connor favorite “Moonride”, with a hilarious spoken section about an interaction with a space alien. Two selections were composed for Abbey Lincoln by the obscure songwriter R.B. Lynch, and there are several pieces inspired by Blake’s love for film noir (including the piano solo “Mahler Noir” which somehow morphs into a version of “Dancing in the Dark”). The closer is a nearly-definitive version of Harold Arlen’s “Last Night When We Were Young” where Serpa and Blake show that they can effectively create a distinctive interpretation with understated dynamic shifts, a rich harmonic background and minimal changes to the melody.

adventurous jazz instrumentalists. Blake’s unusual manner of accompanying with sudden fortissimo bursts and dense complex chords might seem to be anathema to a vocalist, but he and Serpa align their vivid musical imaginations to transform classic songs into intense dramatic experiences. “Aurora”, recorded in Lisbon in May 2012, is the second collaboration between Serpa and Blake, and it expands on the territory they explored on the album, “Camera Obscura”. Here, the selections are longer and there is a greater emphasis on the texts. With a charming Portuguese accent and a pure vibratoless voice, Serpa might initially remind listeners of Astrud Gilberto, but her interpretations reveal a much deeper understanding of the music’s subtext. Consider Serpa’s unaccompanied version of “Strange Fruit”: unlike Billie Holiday, Serpa has no first-hand experience with lynchings, but her stark reading with precise declamations of the key words and subtly nuanced dynamics emits an eerie atmosphere that evokes those tragic events. While the prevailing mood of the album is dark and intense, there are lighter moments, including a delightful version of the Chris Connor favorite “Moonride”, with a hilarious spoken section about an interaction with a space alien. Two selections were composed for Abbey Lincoln by the obscure songwriter R.B. Lynch, and there are several pieces inspired by Blake’s love for film noir (including the piano solo “Mahler Noir” which somehow morphs into a version of “Dancing in the Dark”). The closer is a nearly-definitive version of Harold Arlen’s “Last Night When We Were Young” where Serpa and Blake show that they can effectively create a distinctive interpretation with understated dynamic shifts, a rich harmonic background and minimal changes to the melody.

The perennially underappreciated Jay Clayton has an agile voice and a wide musical palette that covers styles from straight-ahead to avant garde. In the summer of 2007, she recorded a straight-forward set of jazz and pop standards released as “In and Out of Love”, and  a progressive album of solo voice with electronics called “The Peace of Wild Things”. While “In and Out” offers a superb introduction to Clayton’s adventurous scat and sensitive lyric readings, “Peace” may be her best-realized album. At first glance, a 41-minute album of solo voice might seem unapproachable, but Clayton creates a rich collection of unique soundscapes with a wide variety of vocal techniques and electronic equipment. She freely mixes speech and singing in her interpretations of poems by e.e. cummings, Jeanne Lee, Lara Pellegrinelli and Wendell Berry. The electronics, which include synthesizer, harmonizer, loop pedal, digital sequencer and bass pedal, offer a layered sound that enhances the words and presents a stunning background for Clayton’s ear-bending improvisations. On the title track, she creates a choir from her own voice, and on “No Words, Only a Feeling”, she sings a great improvisation over a looped vocal bass line. The bass pedal evokes an otherworldly atmosphere in “Sheila’s Dream” and the wind chimes on that track were digitally sampled on the porch at subject Sheila Jordan’s home. The most effective track is “Sometimes”, the only composition featuring both lyrics and music by Clayton. The title word summons a range of emotions in Clayton’s poem: Sometimes I wonder/Sometimes I think I know/Sometimes I’m not so sure/Sometimes I just don’t care. In the closing chorus of the piece, Clayton lets the electronics overlap the lines to show that these emotions are not exclusive of each other and that they usually coexist. Of course, there are plenty of artists that can create these soundscapes in a recording studio with overdubs and multi-track tape, but Clayton created all of this music live in the studio, bringing in a few pre-recorded samples and producing the rest in real time. In itself, that’s quite an accomplishment, but the creation of uniformly high quality music at the same time is what makes this album a masterpiece.

a progressive album of solo voice with electronics called “The Peace of Wild Things”. While “In and Out” offers a superb introduction to Clayton’s adventurous scat and sensitive lyric readings, “Peace” may be her best-realized album. At first glance, a 41-minute album of solo voice might seem unapproachable, but Clayton creates a rich collection of unique soundscapes with a wide variety of vocal techniques and electronic equipment. She freely mixes speech and singing in her interpretations of poems by e.e. cummings, Jeanne Lee, Lara Pellegrinelli and Wendell Berry. The electronics, which include synthesizer, harmonizer, loop pedal, digital sequencer and bass pedal, offer a layered sound that enhances the words and presents a stunning background for Clayton’s ear-bending improvisations. On the title track, she creates a choir from her own voice, and on “No Words, Only a Feeling”, she sings a great improvisation over a looped vocal bass line. The bass pedal evokes an otherworldly atmosphere in “Sheila’s Dream” and the wind chimes on that track were digitally sampled on the porch at subject Sheila Jordan’s home. The most effective track is “Sometimes”, the only composition featuring both lyrics and music by Clayton. The title word summons a range of emotions in Clayton’s poem: Sometimes I wonder/Sometimes I think I know/Sometimes I’m not so sure/Sometimes I just don’t care. In the closing chorus of the piece, Clayton lets the electronics overlap the lines to show that these emotions are not exclusive of each other and that they usually coexist. Of course, there are plenty of artists that can create these soundscapes in a recording studio with overdubs and multi-track tape, but Clayton created all of this music live in the studio, bringing in a few pre-recorded samples and producing the rest in real time. In itself, that’s quite an accomplishment, but the creation of uniformly high quality music at the same time is what makes this album a masterpiece.

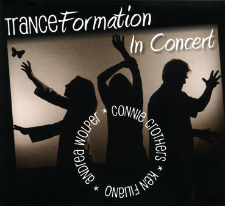

While “TRANCEformation in Concert” differs from “The Peace of Wild Things” in its instrumentation, recording circumstan ces and lack of electronic gadgetry, it is cut from the same cloth as Clayton’s album. TRANCEformation is a leaderless trio with vocalist Andrea Wolper, pianist Connie Crothers and bassist Ken Filiano. The album jacket proudly proclaims that the music and words were 100% improvised and all of the music was recorded live. Like Clayton’s album, several pieces emphasize the spoken word. Wolper’s lightning-fast rant on “The Things You See in New York City” is both funny and realistic, both in the images and the delivery. On the other end of the spectrum, “The Same Moon” is an impressionistic view of human perception. A further connection with Clayton’s album is a piece called “Sea Island Sometimes” which seems to take its initial inspiration from Clayton’s “Sometimes” before taking its own direction. Yet, the similarities to Clayton’s album only serve to point out its differences. TRANCEformation’s pieces are created without any forethought, so the performances are necessarily looser and less predictable than Clayton’s arrangements. Plus TRANCEformation’s combination of instruments and voice creates a massive sound, brimming with intensity but easily overwhelming. There are times when Wolper is lost in the mix as Crothers and Filiano improvise against each other. That may be the reason why the bass/voice duet “Lines and Circles Squared” is one of the best tracks on the disc—nothing against Crothers, but the lean accompaniment seems to favor Wolper’s voice. As has been said on many occasions, even “free jazz” had its rules and structure; by avoiding those guidelines, this music takes great risks at every turn. Like the other albums in this survey, “TRANCEformation Live in Concert” is not for every taste, but for those willing to go along, it is a fascinating journey.

ces and lack of electronic gadgetry, it is cut from the same cloth as Clayton’s album. TRANCEformation is a leaderless trio with vocalist Andrea Wolper, pianist Connie Crothers and bassist Ken Filiano. The album jacket proudly proclaims that the music and words were 100% improvised and all of the music was recorded live. Like Clayton’s album, several pieces emphasize the spoken word. Wolper’s lightning-fast rant on “The Things You See in New York City” is both funny and realistic, both in the images and the delivery. On the other end of the spectrum, “The Same Moon” is an impressionistic view of human perception. A further connection with Clayton’s album is a piece called “Sea Island Sometimes” which seems to take its initial inspiration from Clayton’s “Sometimes” before taking its own direction. Yet, the similarities to Clayton’s album only serve to point out its differences. TRANCEformation’s pieces are created without any forethought, so the performances are necessarily looser and less predictable than Clayton’s arrangements. Plus TRANCEformation’s combination of instruments and voice creates a massive sound, brimming with intensity but easily overwhelming. There are times when Wolper is lost in the mix as Crothers and Filiano improvise against each other. That may be the reason why the bass/voice duet “Lines and Circles Squared” is one of the best tracks on the disc—nothing against Crothers, but the lean accompaniment seems to favor Wolper’s voice. As has been said on many occasions, even “free jazz” had its rules and structure; by avoiding those guidelines, this music takes great risks at every turn. Like the other albums in this survey, “TRANCEformation Live in Concert” is not for every taste, but for those willing to go along, it is a fascinating journey.